Kentucky Proud’s ‘local food’ not so local

April 4, 2016

What are Kentucky Proud products?

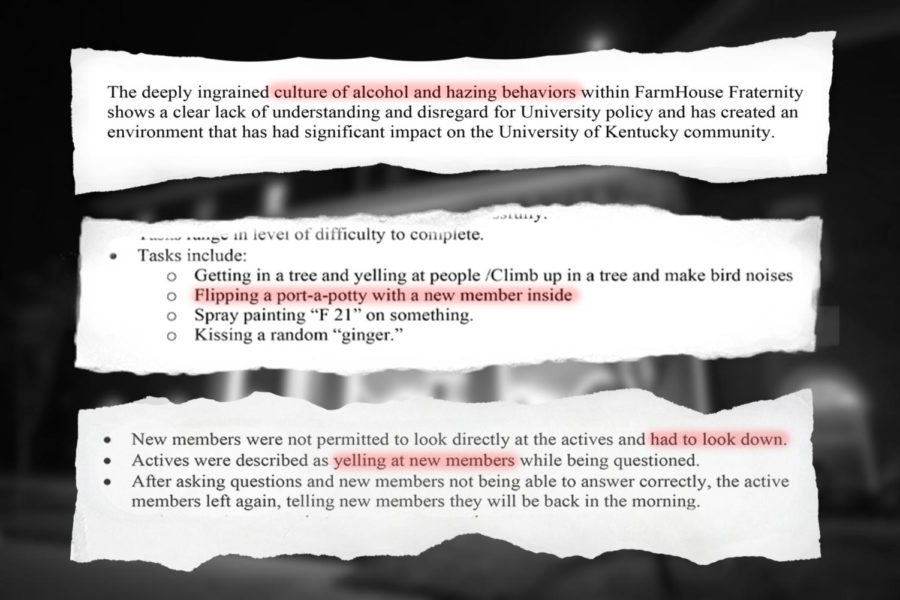

When Aramark signed a contract with UK requiring a yearly, increasing quota of $1.2 million for Kentucky Proud products, supporters of Kentucky’s local food movement rejoiced.

In its first year, though, Aramark included in its “local” purchases more than $1 million of Coca-Cola products, $45,000 of Home City Ice and $39,000 of Pepsi products.

Kentucky agriculture is a more than $5.2 billion industry with about 76,000 farms in operation — not to mention its other producers in the state, like distilleries and breweries.

But when it comes to the food served at the state’s flagship, land-grant university, and in many of the state’s restaurants and groceries, corporate commodity food distributors dominate the market.

When the Kentucky Department of Agriculture agreed to fund the Kentucky Proud Association, the hope, according to John-Mark Hack, executive director of the Local Food Association, was that Kentucky farmers’ sales would increase through branding initiatives and through fostering pride among residents for their state’s farming community.

In the last year, though, Hack has been one of Kentucky Proud’s main critics, pointing out faults in its ability to exclude businesses that have no place in, or economic impact on, Kentucky’s agriculture. He cited Coca-Cola, one of Kentucky Proud’s vendors, as a prime example of the problem.

Hack and other members of the state’s local food movement have advocated for changes in labels of Kentucky Proud products to match the classifications the organization allows: farmers, producers, manufacturers and distributors of food in Kentucky.

For many of Kentucky’s farm families, the organization has made an impact in their marketing and the brand is well recognized, according to surveys conducted by the Department of Agriculture.

Ben Shaffar, a Kentucky Department of Agriculture and Kentucky Proud representative, said the goal of Kentucky Proud is “opening up new markets and having a direct impact on our farm families.”

Shaffar said Kentucky Proud has about 5,300 members with 20 new applicants for the program each week, and so the demand is extensive for assets that Kentucky Proud supplies.

These assets include incentives for restaurants to use Kentucky Proud products by receiving up to $12,000 back per year, as well as grants for farms and other marketing assistance for agricultural businesses in Kentucky.

Kentucky Proud receives its funding from the 1998 Master Tobacco Settlement, not taxpayer dollars. According to Shaffar, any monetary assistance it provides goes toward direct farm impact, such as grants.

But the program, in the eyes of the local food movement, is so inclusive that it has local farmers competing with corporate businesses under one brand.

“Kentucky Proud is a consumer marketplace focused branding initiative. It’s not job creation. Our intent … is all about increasing farm sales for our families and our businesses as well,” Shaffar said. “Everything that we do is focused on opening up new markets and having a direct impact on our farm families.”

Hack said that he has full confidence that Agriculture Commissioner Ryan Quarles will strive to improve the program during his time in office.

According to data from Kentucky Proud, 935 participants of Kentucky Proud in 2014 were farmers — fewer than half of its total members that year.

This was a year after it purged its system from the time of its inception in 2004, and the administrative check cut its numbers in half, according to Shaffar.

Scott Smith, faculty director of UK’s Food Connection, said few Kentucky Proud members are actually local farmers like many consumers perceive them to be.

“There has been a perception developed and nobody has tried to correct it — that Kentucky Proud means it helps Kentucky farmers in a direct way,” Smith said. “If you think of it as a way to inform consumers about where their food comes from, many questions could be asked about that.”

This does not mean that most, if not all, of these members do not have an effect on Kentucky farms.

“Kentucky Proud, as a program to promote food and agriculture in general in the state of Kentucky … is a very successful program,” Smith said. “Most of those participants are food processors or vendors, or restaurants or others, who are selling products off the farm. Some of those will be farm stands or direct-to-farm sales.”

Smith also said big commodity farmers in Kentucky, who have little need for the incentives or marketing of Kentucky Proud, may appreciate it for increasing awareness about locally grown food.

Though scrutinized by many members of the local food movement, Kentucky Proud’s goal is to develop and research ways to improve Kentucky’s agriculture industry for its farmers, which it does — along with corporate food commodity distributors.

Does Kentucky Proud help Kentucky

farms?

One of the main setbacks to Kentucky Proud’s self-advocacy is the lack of metrics showing how sales have changed for its vendors since enlisting in the program.

Shaffar said Kentucky Proud is still gathering data from some of the few farmers who are willing to open up their books to them, but increased consumer purchases, increased partnerships with distributors and an increased number of participants in rebate programs for buying Kentucky Proud products are signs that it is helping the local food economy.

However, this same executive summary concurred with the attitudes of local food advocates about what they believe is Kentucky Proud’s main shortfall: a lack of Kentucky labor and ingredients.

“The expert meetings and project interviews indicated a concern that the Kentucky Proud program may have diluted the effectiveness of their brand by not requiring a product be made with a majority of Kentucky-grown ingredients,” the summary said.

Kroger and Walmart, two of the state’s largest groceries, have made agreements to partner with Kentucky Proud and carry its products in their stores.

“Increase in statewide brand awareness … has been ushered in, not only through our efforts here at the department,” Shaffar said. “We are increasing distribution of product and also point of sales.”

While companies that are not based in Kentucky can still wear the Kentucky Proud label because of the wide acceptance of its program, Shaffar said that any financial assistance the group gives goes toward direct farm impact.

According to a study conducted by the Department of Agriculture, many consumers polled would like to support local agribusinesses, even by paying between 5 to 15 percent more for the product.

Kentucky Proud’s Restaurant Rewards program alone includes more than 350 restaurants and had a revenue of about $2.9 million in new farm income, according to a study conducted from 2007 to 2014 by the Kentucky Agricultural Development Fund and the Kentucky Agricultural Finance Corporation.

“The expert meetings and project interviews indicated a concern that the Kentucky Proud program may have diluted the effectiveness of their brand by not requiring a product be made with a majority of Kentucky-grown ingredients,” the summary said. “A rating system that gives a higher score for an all in-state product could provide a boost to consumer confidence in the label and add confidence in the Kentucky Proud label.”

The group’s recommendation, for which both Hack and Smith advocated, was for a new labeling system that rated the product in hopes of correcting misguided perceptions of Kentucky Proud products — namely that all of the products come from Kentucky farms.

“The Kentucky Proud program as it currently exists has been very successful at raising consumer awareness of the availability of products that are produced by Kentucky farmers,” Hack said. “In order to reduce confusion at the marketplace, a regular monitoring of the Kentucky Proud vendor list ought to be conducted. If it is not, then there is really no need for the program to exist.”

Lilian Brislen, executive director of the Food Connection at UK, said there is another perception of Kentucky Proud’s vendors that consumers are confused about.

“You use a label like that when you’re at least one step removed from the buyer, so that

they can verify (that it comes from a local farm),” Brislen said.

Most CSAs and farmer’s markets do not need the label to market their products’ “local” impact — the consumers they serve already know that. The label serves more the needs of processors and distributors than it does many local farmers.

According to the 2007 Census of Agriculture, 35 percent of all Kentucky farms are between one and 49 acres, and about 89 percent of all farms made less than $49,000 in sales each year.

This class of farmers is where many small productions and a few non-commodity producing farmers fall. Because it is more difficult to manage many small producers than a couple large ones, distributors requiring the label will only pick up the top tier of those small farms.

Kentucky Proud has enabled many farmers to gain access to markets they had not reached before, and established business partnerships that will give them a secure income.

But to many members of the local food community, this comes at the expense of the consumer’s perceptions and competition for the brand with corporate distributors.

Faults of the program

As mentioned in the executive summary by KADF, some farmers and producers in Kentucky feel as if issues limiting the scope of the project hurts or dilutes the value of their product.

Another administrative problem of the program is the lack of oversight the Department of Agriculture can provide.

“As far as a police force to go out to every single farm, obviously we do not have that,” Shaffar said. “But we know that farmers are pretty good tattletales. So fortunately we haven’t had too many (who) abuse the program. We do reserve the right to audit at random.”

The first time the system was purged in 2012, more than half of Kentucky Proud’s members were not readmitted to the program because they had either discontinued their business, the owner died, or the business went outside the definition of the program, Shaffar said.

This system of good faith leaves room for actual farmers to fall by the way side, as Stephen Fister, owner of Bi-Water Farm and Greenhouse, said has happened because of the strength of processors in the program.

“Well we do have a problem with (Kentucky Proud members) promoting products in Krogers and other chains — because it started out as for the farmers,” Fister said. “Now it’s turned into who can be the biggest processor of the farm product. And so for the actual farmers themselves, unless you’re a big processor, they do no good for you as far as selling in Krogers and that sort of stuff.”

Fister said the process still benefits Kentucky agriculture, but more so processors than farmers.

“Now does it move (Kentucky) products? Absolutely it does. But if you look at it, it’s more processed foods — jams, jellies, that sort of thing,” Fister said. “They have a certain amount of fresh produce they sell that’s (Kentucky) Proud, but the majority is processed foods.”

Kentucky farmers

The driving force that powers Kentucky Proud are the countless local farmers throughout the Commonwealth whose blood, sweat and tears go into providing all Kentuckians with fresh and locally-sourced produce.

Founded in 1959 by Carl and Bertha Fister, Bi-Water Farm and Greenhouse has been a mainstay in Kentucky farming and agriculture. Today, their three sons Stephen, Chris and Len watch over the farm, which grows produce, tobacco and corn, and raises hogs to boot.

According to Stephen Fister, the initial certification process for Kentucky Proud was simple.

“We have to apply for the (Kentucky) Proud usage of the logo,” Fister said. “We also have to tell what products you’re issuing under that … what products you grow, what products you raise. Those are then considered and you have to meet certain criteria.”

Bill Kamman of Pop’s Pepper Patch agreed that becoming certified Kentucky Proud was easy. Kamman said he has Kentucky Proud certificates on his office wall dating back to 2005, and he holds certificate number three, meaning he has one of the first businesses to become Kentucky Proud certified.

While Kentucky Proud has brought success to Kamman and his pepper farm, the struggles of competing against large corporations and factory farms still frustrate him.

“You can’t really compete against them,” Kamman said. “My philosophy is it’s almost a David versus Goliath attitude … It’s us against them.”

Hack said it is imperative that an effort be jump-started to create a class of products that are strictly grown on Kentucky farms, and that have distinguished labeling from products manufactured in the state, but not grown on Kentucky farms.

“Right now there is a tremendous amount of confusion in the marketplace in which consumers are lead to believe that their purchases are somehow benefiting their neighbors and community because they think the products are coming from Kentucky farms, when in many cases they are not,” Hack said.

According to Hack, the intent of the program as it was sold to its funder, the Agricultural Development Board, was that it would promote the sales of Kentucky farm products. While that has been the case, corporate America has also joined the grassroots campaign.

Kentucky producers

While the initial thought behind Kentucky Proud was to promote and provide easier access to local food, the label has opened doors for other local craftsmen and women to test the waters with products ranging from bath soaps to candles.

As farmers and businesses have thrived under the program, people have begun working together, forming a diverse intertwining network of farmers, producers and distributors throughout the state who all want to see one another succeed both financially and in terms of bringing affordable, healthy, sustainable food to Kentuckians. Head chef at Smithtown Seafood Jon Sanning is one of those who goes out of his way to support local.

“I just try to buy as much locally as possible, obviously there’s things you can’t,” Sanning said. “Nobody’s out growing 50 pounds worth of onions for $20 … but we try to utilize as much as possible. When say FoodChain is running short, we do Bluegrass Aquaponics for some stuff, out in Midway.”

Whenever Sanning needs to turn to FoodChain for product, he can trust owner Becca Self’s thorough process for hydroponic plants and harvesting fish that she then sells to Smithtown and other restaurants.

According to Self, they hatch their own baby tilapia. When born, the babies take about six months to grow to a suitable size. After that they are moved into the main aquaponics system, and their waste travels down to filtration tanks. Some solid waste is removed to prevent pipes from clogging, and the remaining waste is converted into nitrate by bacteria. The bacteria feed off the waste, turning it into nitrate, yielding a nutrient-rich water.

The fish are fed with spent grain from nearby West Sixth Brewery. Most of their food goes to Smithtown, but the remainder goes to other local restaurants in order to limit the producer-to-consumer distance.

“We started with a pretty big vision, not only with the food production but also growing into food preparation and distribution with a store,” Self said. “It was a lot of knocking on doors and talking to anybody and then some. We had a lot of individual donors, which I think has really contributed a lot to the success of FoodChain because there’s a lot of people who feel like they’re part owners of it.”

Self said while Kentucky Proud cannot avoid being political in certain aspects because it is a program of the Department of Agriculture, she cannot help but be thankful for everything it has done to benefit and promote local farmers and food.

Kentucky distributors

The final group vying for a slice of the financial pie is Kentucky Proud’s vast network of distributors. Sean Haggerty, an independent chef who has teamed with Louisville-based Bluegrass Brewing Company, said that while selling his sauces in stores throughout Kentucky is often more profitable when he buys products from larger farms, the benefits of doing business with other local farmers and producers has benefits important than the loss of profit.

“If we just manufactured it here it would still be certified Kentucky Proud, but we strive to get local ingredients as well,” Haggerty said. “Being in the business a long time I’ve met a lot of farmers, and that’s really the direction in which our food source needs to come — growing local. Mass-producing farms, GMOs and Monsanto is tearing our kids apart — tearing our own health apart.”

One of the many local vendors Haggerty works with through the BBC is Bill Kamman at Pop’s Pepper Patch. Haggerty turns to Pop’s for peppers he uses in his signature Cajun relish, which is available at more 60 Kroger stores, Liquor Barn, and several local businesses throughout Kentucky. According to Kamman, who’s been in the pepper and local farming business since 1994, momentum has been building in the last six or seven years for supporting locally grown foods.

“Evidently there were certain retailers who were watching the movement and Kroger chose Kentucky to start a pilot program for buying local,” Kamman said. “They’ve done so well in the state of Kentucky, I believe they’re looking to start programs in the neighboring states of Tennessee, Indiana and Ohio.”

Kamman’s distribution network for Pop’s Pepper Patch runs from Bowling Green to Eastern Kentucky. Kamman uses five distributors. The first is based out of Bardstown and distributes to gourmet, retail, and mom-and-pop shops. He has another that deals with his multi-state sales to Kroger, and another that handles bi-local sales to the grocery distributor. Kamman’s final two distributors are based out of Louisville and Salt Lick, Kentucky, respectively.

Scott Smith, faculty director of the Food Connection at UK, a program that seeks to develop solutions and creative strategies for more sustainable, healthy and affordable food at UK and in Kentucky, has also noticed an upward trend in advocating for local food.

“Over the last 10 years it has really changed tremendously,” Smith said. “There were no restaurants who were interested in food sourcing and those kinds of things. Now there are really quite a few.”

Smith said UK’s partnership with Aramark is utilizing Kentucky Proud in its contract as a means of measuring local food purchasing. For the first year of the contract, Aramark was required to purchase no less than $1.2 million of local food from Kentucky, an amount that increases every subsequent year in the contract.

One large complaint about Aramark and other large companies under the Kentucky Proud label is the leniency in what is classified as Kentucky Proud. For example, Aramark’s largest Kentucky Proud distributor is Coca-Cola since there’s a bottling plant in the state, although critics have said Coca- Cola is not local, whether it is bottled in Kentucky or not.

According to Sanning, that labeling becomes even more mysterious under the microscope of meat.

“You get into that fuzzy protein situation where cows are born here, they’re shipped off to finish, they come back,” Sanning said. “You ship a cow to Nebraska or something for the last 80 days of its life, they ship them back, you don’t know if they’re your cows. So it’s just a processing thing.”

From his experience at Smithtown, Sanning said people appreciate locally-sourced food when they come across it, but do not often go out of their way to find it. While fast food restaurant sales are on the decline, millions of Americans still eat at those restaurants every day, although more people are beginning to explore their local cafes and restaurants. Sanning said that that to “talk the talk” of buying local, one has to “walk the walk.” That’s why all the food items purchased for use by Smithtown Seafood are certified Kentucky Proud.

Self, owner and operator of FoodChain, started the nonprofit on the northwest side of Lexington because the surrounding neighborhood didn’t have enough access to fresh food.

“We’re in a food dessert, which means we’re more than a mile away from a grocery store, which is where most of our fresh food needs to come from,” Self said. “It happens to be a community that has a high population of low income. The problem of lack of access is exacerbated in this community. Another foundational point of FoodChain is that Kentucky as a whole has fairly dire health statistics.”

Self said to encourage businesses to go Kentucky Proud, restaurants will often be rewarded certification simply for using local tomatoes for a small portion of the year while they are in season because buying local is often much more difficult than going to the big distributors.

“It’s still not as easy as ordering from a broad line distributor, but I think that those restaurants have gone one step in the right direction by saying, ‘I am going to incorporate local food,’” Self said. “Would I like it to be more? Absolutely.”