He ‘paved the way’ for integration at UK. Who was Lyman T. Johnson?

September 20, 2019

This year marks 70 years since one man changed higher education in Kentucky forever.

This year marks 70 years since Lyman T. Johnson, won his suit against the University of Kentucky, and officially desegregated UK’s graduate school.

In the years before 1949, UK’s graduate school was completely segregated. If a black student wanted to attend graduate school, they were required to go to Kentucky State College at Frankfort.

Much of the black community viewed Kentucky State College as unequal to the level of education white students were receiving at UK, Johnson said in a 1987 interview conducted by Doris Weathers for the University of Kentucky’s oral history project. But black students had no other options for graduate school in Kentucky.

“This was the case until I came down the pipe in 1948,” Johnson said of when he filed his case against UK.

According to a 1949 article in the Kentucky Kernel, Johnson sued UK after two failed attempts to enroll in the school’s graduate program because of his race. The university held the stance that black and white students should not attend the same school, a stance that many institutions across the nation held.

Johnson argued that there was no school that hosted only black students that had equal levels of education to UK. In 1948, he took his stance to court.

“Back in the 1940s, there were a bunch of young educators, mainly, but civil rights leaders in particular, beginning to grow out of the young man into the middle age,” Johnson said in his 1987 interview. “We were concerned about how to get some black people into the University of Kentucky, the University of Louisville or any other all-white colleges and universities as a matter of right on their part.”

In his interview, Johnson tells a story of something he experienced in segregated society. One day, he and his daughter were walking home, and she had to use the restroom. But since Johnson and his daughter were black, they were unable to simply walk into a store so she could. He said a white man could walk into any store or hotel they wanted if they were in the same situation, but he and his daughter couldn’t.

It was situations like these that inspired him to challenge higher education in Kentucky, despite many telling him to give up.

“I am not going to let anyone convince me that I was wrong for raising hell about it,” Johnson said.

According to Johnson, he challenged UK on the basis of the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court. This case established that institutions may separate people based on race, but the separated institutions must be equal to one another.

By April of 1949, Federal Judge H. Church Ford ruled that UK must admit black students to the university.

“Judge Ford said the testimony showed facilities at Kentucky State College at Frankfort were not equal to those at the University,” the Kernel reported.

He ruled that until there was an equal program in Kentucky that black students could attend, UK’s graduate program must desegregate.

“Until the state shall establish a graduate school substantially equal to the graduate school at the University of Kentucky, it must admit Negroes on the same basis as whites,” Judge Ford said in his ruling.

Johnson, and other black students, were now legally permitted to enroll in UK’s graduate program.

Though the ruling was a success for black students across the state, there was still much fear of retaliation from students and teachers attending UK at the time. Because of this fear, Johnson started school in the summer of 1949 as a 43-year-old graduate student, a time of year where fewer students would be on campus.

“A lot of times when something is occurring for the first time, people don’t quite know how to react on either side,” George Wright, a UK alumnus and now Texas A&M professor said. “Notice I didn’t necessarily say people were hostile, but it’s hard in a lot of instances for folks to reach out to, quote, ‘the other side.’”

Wright has been brought to UK this school year as a visiting professor of history. His presence on campus is part of the celebration of the school being integrated for 70 years.

Back when he was still in graduate school, Wright wrote his doctoral thesis on Johnson, whom he met in the early 1970s, around 25 years after Johnson had challenged UK in a legal battle. He wanted to find out about the history of black people in Louisville, where Johnson lived and taught high school history, economics and mathematics.

In Wright’s interviews with Johnson, he found that not only did Johnson never graduate from UK, but he never intended to graduate from the program he was enrolled in, the master’s program of history. Instead, Johnson’s goal was simply to make it possible for future black students to be a part of the graduate program.

“And it was the same in a lot of the states, such as Texas where I have lived for many years,” Wright said. “The first black student admitted to law school there did not intend to graduate.”

Wright said Johnson came and took courses to “open the doors for other students.” The intention was never to graduate, but to pave the way for prospective black UK students.

“Ironically, 19 years later, I enrolled at as a history undergraduate major at UK,” Wright said. “I wasn’t the first, but you see, he had opened the doors for us. I would eventually go to graduate school in history at UK. He had opened the door for people like me and for many people that I didn’t even know.”

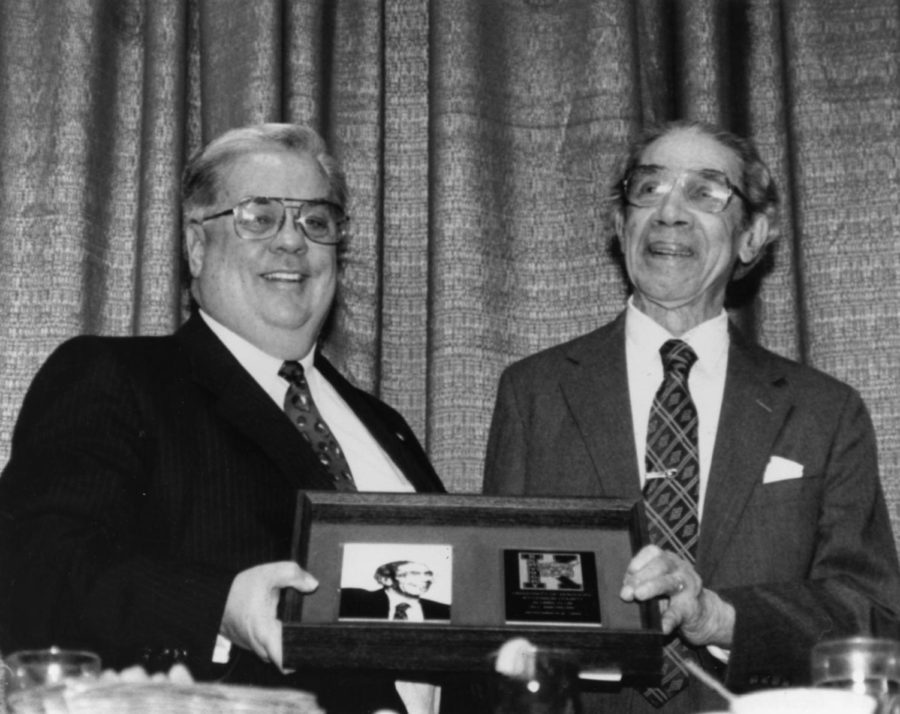

Though Johnson never graduated from UK, Wright said Johnson was given an honorary degree by the school 30 years later.

Johnson died in 1997, but his legacy at UK still lives on. In 2015, the university named a dormitory after him, Lyman T. Johnson Hall, located on Hilltop Avenue across from the William T. Young Library. Among this, there are awards available to students in his name, such as the Lyman T. Johnson Diversity Fellowship.

Now, 70 years later, UK is honoring what Johnson did, even though they were on the other side of the lawsuit so many years ago.

“We recognize this year-long event as a commemorative anniversary of 70 years of integration rather than a celebration,” Vice President of the Office for Institutional Diversity at UK Sonja Feist-Price said. “This time of remembrance allows us to reflect on our journey… For African Americans, this journey began with Mr. Lyman T. Johnson; however, his impact transcends race/ethnicity and speaks to the rich diversity, inclusion and belonging we currently have and seek to enhance.”

In the fall semester of 2019, UK has 2,011 enrolled black students into both the undergraduate and graduate programs.

“Mr. Johnson would encourage us to continue pushing the wagon up the hill,” Feist-Price said.