UK research team develops enzyme-embedded antiviral mask

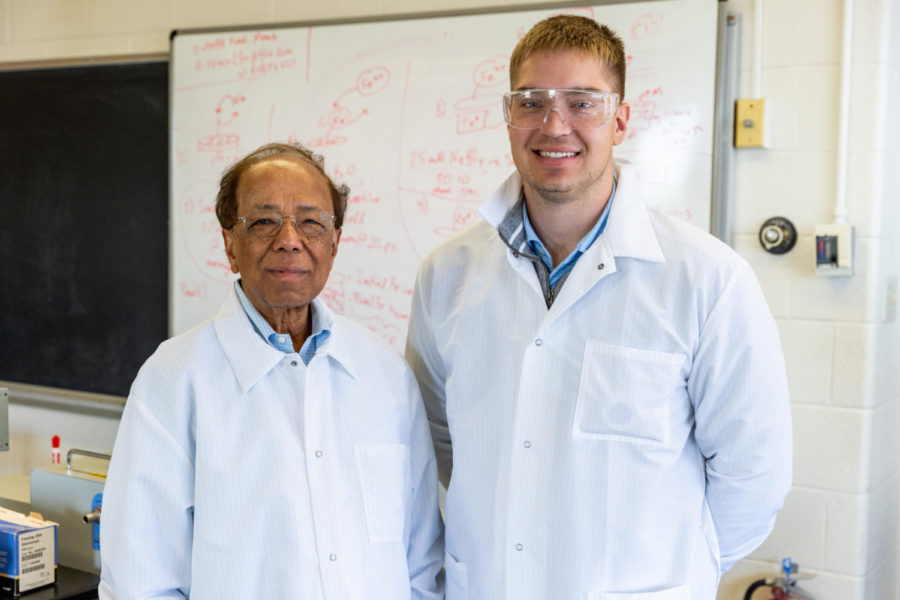

Dibakar Bhattacharyya, left, and Rollie Mills pose for a photo on Thursday, Sept. 29, 2022, at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, Kentucky. Photo by Jack Weaver | Staff

October 5, 2022

University of Kentucky professors, undergraduate students and graduate students from a variety of vocations developed an antiviral mask to combat COVID-19 and other viruses.

This 12-person team is led by Dr. Dibakar Bhattacharyya, director of the Center of Membrane Studies. Bhattacharyya has worked in chemical engineering at UK for around 50 years. He began working on the antiviral mask project in April 2020, shortly after the first cases of coronavirus were found in the United States.

The mask contains enzymes that attach to the spike proteins found in many viruses like COVID-19. The enzyme then deactivates the protein so it can no longer harm the human body.

Two of the many people on the research team were Todd Hastings, professor of electrical engineering and the director of the Center of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, and senior chemical engineering student Matthew Bernard.

“Although I am listed as the PI (principal investigator), there’s a lot of people involved,” Bhattacharyya said.

He added that without everybody on the research team, the project would have never taken off.

Bernard said that his role in the project was working with the spike proteins. The mask needed to not only be able to take out the proteins that bind with human cells, but also destroy them so if they are able to get through the mask they can’t infect the body.

Bernard was responsible for developing an enzyme-embedded membrane for the mask material, testing it with the spike proteins and designing a way to see the results. The team used a dye that would bind to the inside of the proteins when it broke apart.

Hastings worked with light scattering to detect when particles passed through the mask material; when particles pass through the material, laser light scatters over, exposing the particles. Hastings said that Ph.D. student Rollie Mills was a pivotal part of this process as well.

Other aspects of the project included developing a hydro-gel to keep the enzymes alive while on the mask. Bernard described it as a “micro-environment where the enzymes can hang out.” The mask can be used as defense against many different viruses as well as the several variants of coronavirus.

The project is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). Bhattacharyya said that the University of Kentucky’s facilities, departments and support centers were also crucial to the research.

“It’s not just the equipment, but it’s having all the people,” Bhattacharyya said.

He said that without the diversity of the people, their backgrounds and their knowledge as well as the accessibility of research, the project would have been extremely difficult to pursue, if not impossible. Students, professors and researchers of biology, chemistry and engineering were integrated to form the team.

The team has applied for a patent on the product; until the masks are patented, Bhattacharyya said they are not available for use. However, he said that money was never the goal.

“My satisfaction for this project is not making money,” Bhattacharyya said. “It’s saving the lives of people.”