Treating the disease, not the symptoms: A glimpse into the Fayette County Mental Health Court

May 19, 2022

*** The names of the participants in the Fayette County Mental Health Court have been changed using a random name generator due to privacy concerns. ***

The last time Elena had a drink was October 17, 2020, her 21st birthday. She quit using drugs several months prior, on August 31. The last time she refused to take medication for her mental illness was July 31, 2020, the day she spent eight hours in jail after assaulting her ex-boyfriend. She doesn’t wish to repeat that experience, she said.

Now, Elena, 22, is sober and taking new medication that works. She said she has learned to be honest with herself, and hold herself accountable for “all the good, bad and ugly things” she has done. For the first time in a long time, her future plans are full of hope.

Elena is one of the most recent graduates of the Fayette County Mental Health Court, an alternative sentencing court authorized by the Kentucky Supreme Court for criminal defendants suffering from serious and significant mental illnesses. Defendants who meet certain criteria are eligible for this diversion program, which lasts at least a year and combines case management, judicial oversight, treatment, mental health assessments and drug testing in an attempt to push participants toward healthier lives with stable mental health treatment, housing and employment.

The Fayette County Mental Health Court was borne out of a January 2013 city taskforce addressing Lexington’s homelessness problem. Under then-Mayor Jim Gray, the taskforce studied models across the country and met monthly to form the pilot program that would become the first mental health court diversion program chiefly operated by a consumer organization, NAMI Lexington, instead of the courts.

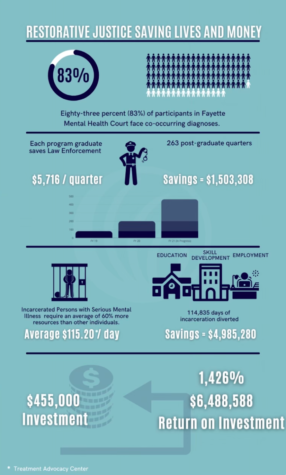

Since its November 2014 launch, the mental health court has served 127 people, 45 of whom have successfully graduated, and 17 of whom are still actively working through the program’s four phases, according to Jennifer Van Ort-Hazzard, a mental health court coordinator at NAMI Lexington.

The program has saved Lexington jails thousands of dollars by reducing recidivism rates, according to NAMI Lexington’s annual reports. Other Kentucky counties have taken notice and are considering replicating the program in their respective communities, Ort-Hazzard said.

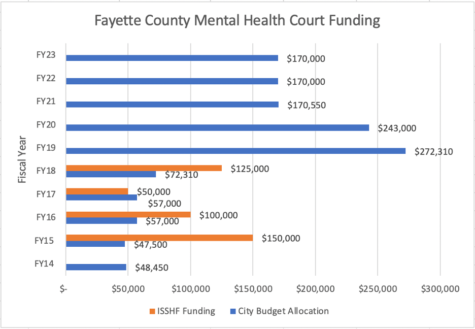

However, since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the mental health court has received significantly less money from the city of Lexington to conduct its operations and serve its participants. After receiving record city funding in fiscal years 2019 and 2020 — $272,310 and $243,000, respectively — the program’s allocation has dropped to approximately $170,000 in the years since.

A monster lives in Julie’s mind.

“He comes and goes as he pleases. He tells me lies. He’s sneaky and rarely gives signs that he is coming. I just wake up one day and he’s there,” Julie said.

Julie does not know how long the monster will stay. There is no rhyme or reason. But she does know what he will tell her — everyone is against her, God isn’t real and she isn’t good enough to live.

Before participating in the Fayette County Mental Health Court, whenever Julie told doctors about the monster, she was merely met with a blank stare and another round of prescription medication that never evicted the monster from her mind.

After graduating from the program, though, Julie is able to distinguish between her thoughts and the thoughts of the monster. She knows that she is not alone in her struggle with mental illness, and that she can retain control.

The goal of the Fayette County Mental Health Court is to reduce recidivism, or repeat offenders.

Connie Milligan, one of NAMI’s licensed clinical social workers, said that while severe mental illness is found in just 4% of the general population, it occurs in 17% of jail inmates. Nationally, 72% of those with a severe mental illness also have a co-occurring disorder, such as substance abuse, and in Lexington, the figure is nearer 90%, Milligan said.

Putting repeat offenders with severe mental illnesses in jail over and over again only treats the symptoms of the problem. The Fayette County Mental Health Court aims to address the cause too, “developing a model of justice” in the process, Milligan said.

The program is headed by the Lexington branch of National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), a nonprofit whose mission is to provide support, education and advocacy for those affected by mental illness. This is unique; out of 533 mental health courts nationwide, Fayette County’s is the only one run by a consumer organization.

This was an intentional choice. The program’s removal from total court control and operation allows multidisciplinary teams consisting of clinical specialists, court officials and peer support networks to intervene in participant’s mental health journeys on an individualized, case-by-case basis. There is no pressure for a “cookie-cutter” solution, said Judge John Tackett, which allows participants the freedom to make progress on their own timeline with the exact right combination of support services they need.

“One thing about this program that’s different than other mental health courts is that it was really homegrown. They didn’t take somebody else’s model and say, ‘Oh, we’ll try to implement it here,’” said Polly Ruddick, director of the Office of Homelessness Prevention and Intervention. “It was really grassroots efforts of, like, these are the gaps we’re seeing, this is what we see works, let’s put a program together. And that’s what made it innovative.”

Ruddick witnessed NAMI’s creation and growth firsthand through her involvement in the Office of Homelessness Prevention and Intervention’s fund for new, startup programs intended to combat homelessness in Lexington. This fund, the Innovative and Sustainable Solutions to Homelessness Fund, provided NAMI Lexington with seed money to operate the mental health court between 2015 and 2018.

After four years, the city of Lexington decided to take over this funding, making the mental health court a permanent line item in the official city budget.

However, the pandemic has slowed the program’s growth. The program temporarily transitioned to virtual groups, daily texts and hybrid court sessions in place of its normal in-person programming. It also suffered from an operating revenue standpoint, incurring significant losses in city funding.

“We were successful in becoming that line item, but then became susceptible to the waxing and waning of city budget and the needs of other social services and experienced cuts accordingly,” Ort-Hazzard said. “Enter COVID and monies for the city to use to bolster the finances for social services as related to COVID needs, through which we obtained a short-term expansion grant.”

At 13, Elena told her friend that she didn’t want to be alive anymore. Her friend spilled the secret, and Elena was diagnosed with anxiety and major depressive disorder. Thus began her nine-year journey to come to terms with her mental illness enough to adequately treat it.

Growing up, Elena’s father wasn’t around often due to his struggle with substance abuse, leaving her mother and grandmother as her only familial support system. Elena said she always struggled to regulate her emotions and maintain impulse control. She lived with an extremely high level of anxiety, which she thought was relatively normal. She tried many medications, but inevitably stopped taking them after convincing herself that she would be okay without them and was qualified to make that decision.

“Every time I would do this, something would happen — whether attempting to take my life or self-harming — and I would be impatient again and put on different meds,” Elena said.

This reluctance to accept help extended to Elena’s time as a participant in the Fayette County Mental Health Court.

“Given my life thus far. I wasn’t used to being helped, and I was always the one fixing things, which can take a toll on your health,” she said. “I had to start being selfish and worrying about me first.”

The Fayette County Mental Health Court is not open to all criminal offenders. To be eligible, potential participants must suffer from a verifiable, treatable mental illness that substantially interferes with one or more areas of their life (school, work, relationships, e.g.). This disqualifies those whose mental illness is entirely induced by substance abuse, as well as people who deal with autism, learning disabilities and other incurable conditions.

Sex offenders and violent offenders are also prohibited from participation, according to the court order establishing the program. This includes criminal defendants who are charged with or previously convicted of capital offenses, class A felonies and class B felonies involving serious physical harm or death to victims, for example.

The most common cause for rejection is a lack of a “serious and significant” mental illness that is not fully substance-induced, Ort-Hazzard said. Substance abuse, if paired with a serious and significant mental illness, however, is not an automatic disqualifier.

If potential participants, referred to NAMI by court lawyers and judges, meet these criteria, they are then thoroughly assessed by the multidisciplinary mental health court group, to ensure the willingness of the referred client to fully participate in the diversion court and to begin planning an individualized treatment program.

NAMI partners with dozens of service providers in the community in order to provide each participant with the unique combination of doctors, therapists and other treatment services they may need to treat their mental illnesses and potential substance abuse.

Typically, each participant is involved with at least three service providers throughout the program duration.

Julie’s “monster” — her mental illness — had a tight grip on her before she entered the mental health diversion program. She said that her thoughts and behaviors were controlled by the mental illness, which made her hyper-focus on past mistakes and act contrary to her normal behavior.

The price Julie has paid for suffering from mental illness is massive.

“I am currently serving two consecutive life sentences in a prison that exists in my mind,” she said.

But now, Julie wins against the lies her mental illness, her monster, tells her more often.

“Now, I have the knowledge and the strength to tell him ‘Not today,’” she said.

The program is divided into four phases: stabilization, treatment, self-motivation and wellness. All phases last at least three months and can extend as long as is necessary for staff to believe the participant is ready to move on. In each phase, participants must agree to random drug testing, maintenance of sobriety, attendance of all court dates, appointments with service providers and group meetings and a continued willingness to put in the work toward their mental health goals.

At least twice a month, and typically on a weekly basis, NAMI holds Mental Health Court Sessions, which are confidential, closed proceedings where participants take turns talking about their weeks and receiving feedback and encouragement from their peers.

The first phase is very hands-on, with daily programming and contact with the NAMI team, weekly check-ins with the sentencing judge and the development of key goals for the outcome of the program, including stable housing and employment.

The second phase slightly decreases the frequency of NAMI contact and judge check-ins, contingent on continued progress on goals set during the first phase and a focus on increasing “meaningful daily activities” and social support and relationships.

The third phase further reduces the frequency of required check-ins and is complete when participants have achieved all their treatment and service provider goals. The idea is for participants to have grown to recognize the need to continue the wellness habits introduced in the previous phases for their own sake, not just to complete the mental health diversion program, Atkinson said.

Finally, participants enter the fourth phase, at which point they write their recovery story, participate in aftercare treatment and serve as a peer mentor for other program participants not as far along. Judge Tackett called this peer support “the magic of this court.”

Elena thought mental health court would be easy. She was wrong, she recalled with a chuckle. While she initially believed that she had already worked through the worst of her mental health issues, she learned throughout the process that she actually had a long way to go toward recovery.

During the program, Elena was diagnosed with ADHD and was required to see doctors to receive psychiatric medications and attend therapy. To her surprise, her new ADHD medication worked, and she obtained approval for an emotional support animal, a 2-year-old Australian Shepherd “who helps [her] power through the good and the bad days.”

As Elena worked through the four phases, she not only gradually allowed doctors and service providers to actually treat her, but also allowed other people in, including the same friend who she initially told about her suicidal thoughts many years prior. While Elena strongly disliked therapy and didn’t enjoy some of the more difficult realizations that the program brought, she said she was glad she stuck it out and finally let people help her.

“I could not be more grateful for the tears of frustration and the challenges that it gave me,” she said.

Once participants have successfully completed all four phases and paid all restitution owed to the court, they prepare for graduation. The ceremony takes place at Life Adventure Center and is intended to represent the “closure and release of a period of life and on to the next journey,” according to a NAMI annual report.

Graduation is contingent on participants’ ability to be “fully functioning members of society,” Milligan said, meaning that they are in stable housing, employment and treatment.

Not every participant follows the same timeline, Ort-Hazzard said.

“As we know, recovery is not linear, so we have to be prepared for relapse and resistance as part of the program, so some clients take longer to complete than others,” she said. “Additionally, clients are at varying stages of recovery at entry, so each program is different to speak to each individual level of need.”

Since the mental health diversion court’s inception, it has received 329 referrals. Of these, 278 were assessed (the remaining refused assessment, as the program is voluntary at all stages), 157 were accepted, and 127 were ultimately served.

Of the program’s participants, 45 have graduated, and 17 are still actively involved in the program. The remaining 65 either quit or were terminated due to violations of the program’s rules or of their own volition.

The court’s success does not end after graduation. Of the total number of graduates, 97% are still in stable housing, and 90% remain active in voluntary mental health aftercare treatment, according to Lateisha Ousley Atkinson, a NAMI case worker.

As part of the program, Lexington police began a 40-hour training program to help officers distinguish between mental health issues and other issues when responding to incidents. Due to this training, 6% of all arrests are now diverted to hospitals instead of going straight to jail holding cells, said Heather Matics, Assistant Fayette County Attorney.

Before the pandemic hit, homelessness populations in Lexington had been steadily decreasing since 2014, even as national trends were on an upward trajectory, Ruddick said.

“Programs like mental health courts play a role in that — keeping people housed, keeping people out of the court system,” she said. “We’ll see what the pandemic did to us.”

Mental illness can manifest as any number of self-destructive behaviors. A society or community that only sees and addresses these behaviors, and not the underlying mental illness, can cause more harm than good.

Anyone can become like her, Julie said.

“No one says when they grow up, I want to be homeless, I want to be a junkie, I want to be an alcoholic or all of the above,” Julie said. “But those are just a symptom of the true disease called mental illness. We can keep treating the symptoms and keep throwing thousands of dollars at it. But if you treat the disease, you will no longer have the symptoms.”

The Fayette County Mental Health Court is currently at 50% capacity and looking for new clients, Matics said. As the number of participants increases, the impact of the reduced city funding on the capacity and efficacy of the program will become clearer.

The program currently employs two full-time workers and three part-time workers, Ort-Hazzard said, and is always looking for more volunteers to lead groups on recovery skills, help participants navigate resources and offer encouragement.

Ruddick said that she hopes that NAMI continues to grow, as it offers a desperately needed service in a way that offers individualized help and empathy instead of the coldness of a clinical setting.

“[The caseworkers] don’t have white coats on, and they just get it. Either they’ve been there, or they have really good peers that understand what that person has been through,” Ruddick said. “NAMI can do a lot of good things given the right resources from the state.”

Before July 31, 2020, and her eight hours in jail, Elena was on track to become a nurse. She said it was devastating to lose all progress in the education she had struggled to receive. But after graduating from Fayette County Mental Health Court, Elena said she has plans to eventually re-enroll in nursing school.

In the meantime, Elena is hopeful about the future for the first time in a long time. She left a job of eight years that was making her unhappy and secured her current job, which aligns better with who she wants to be and what she loves to do. She is learning to celebrate her successes without feeling selfish.

“I never thought I would reach 22, let alone actually living a life I enjoy,” she said.