UK receiver Adams completes comeback after life-threatening clot

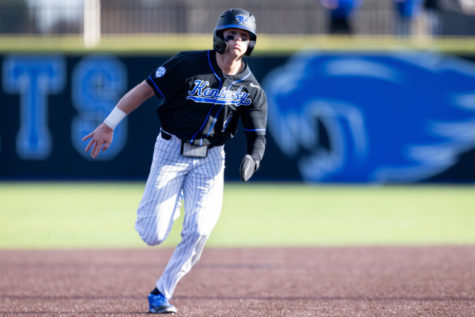

The University of Kentucky Wildcats played the University of Akron at Commonwealth Stadium in Lexington, Ky on Sept. 18, 2010. Photo by Latara Appleby

October 27, 2010

Who knew that one catch could represent so much?

In the third quarter of UK’s 47-10 win against Akron on Sept. 18, redshirt freshman wide receiver Brian Adams snagged his first career reception, a momentous occasion for any player.

The Cats were facing 2nd-and-8, and the UK offense dialed up a mirror route, aptly named because receivers lined up opposite each other run identical routes. With the Akron cornerback cheating up in anticipation of a running play, UK quarterback Mike Hartline scrambled and threw to Adams, who was tackled at midfield following a 13-yard gain.

Yet the play represented more than Adams’ first career catch — it was a culmination of a year’s worth of frustration, disappointment, recovery and hard work. The catch signaled that a football career once suddenly derailed was finally back on track and a life almost lost was enduring.

A season ends before it begins

Adams best summarized his first year on campus: “I was more like a fan than I was a player.”

But not one of the 70,000 fans that fill Commonwealth Stadium could have predicted what was to unfold for the freshman, who was readying himself for a busy summer in 2009.

Following his graduation from South Forsyth High School in Cumming, Ga., Adams, like the other freshmen who had signed to play for the Cats, was set to come to UK for the summer conditioning program offered in early June.

Unlike the other freshmen, Adams arrived in Lexington for conditioning after leading his high school to an appearance in the state baseball tournament finals. The effects of a long baseball season would soon show up as a medical problem that appeared when he went home for the Fourth of July weekend.

It was a problem UK head athletic trainer Jim Madaleno has seen twice before in his career and one that he says someone in his line of work will encounter “once in 15 years.”

Adams called Madaleno and explained that he made a trip to the emergency room because of a swollen right arm, but assured Madaleno, a trainer for nearly the last 30 years, that the blood thinners the doctors had prescribed would take care of a minor clot that existed in his forearm.

Even over the phone, Madaleno had a different hunch.

“I said ‘OK, you need to stay right there, until you’re sure that’s exactly where the clot is because what you’re describing to me over the phone and the fact that you’ve just gone through a couple of weeks of intense baseball and a lot of throwing, I believe there’s a chance you might have some sort of condition that’s called thoracic outlet syndrome,’” Madaleno said.

Thoracic outlet syndrome, though not typical, is most common in baseball players.

Madaleno said that the subclavian vein, which travels from the heart and down the arm, twists and turns at key locations. A baseball player’s muscles in their throwing arm easily become hypertrophied and the vein is squeezed between the top rib and collarbone causing a potential clot.

But because the doctors at his emergency room visit hadn’t mentioned thoracic outlet syndrome, Adams wasn’t convinced he had anything to fret and was more concerned about returning to campus to resume his conditioning. Madaleno refused, telling him he was to stay home.

Disappointed in Madaleno’s decision to forbid him from returning, Adams’ mom, Karen, called the trainer the next day in hopes of swaying him. A stern Madaleno explained the dangers of thoracic outlet syndrome to her, too.

Adams missed a follow-up appointment on the following Monday, much to the chagrin of Madaleno, who insisted that Adams reschedule another follow-up later in the week even if he was feeling normal. But the next day, before Adams got a chance to go to his new appointment, he felt a sharp pain in his back.

“The mother, because of what I put in her mind, took him to a different hospital’s emergency room and mentioned to them about this condition,” Madaleno said.

Doctors had failed to catch a possibly life-threatening clot in his subclavian vein on his first trip to the emergency room. Now, the clot had broken off and gone to Adams’ lungs.

“That can kill you,” Madaleno said. “It needs to be taken care of, what I would call, urgently.”

So a surgeon promptly removed Adams’ first rib to alleviate the pressure on the vein and hopefully prevent future clots. After surgery, Adams was referred to Dr. Daniel Miller, a thoracic specialist and UK graduate, at Emory University in Atlanta. Miller was familiar with thoracic outlet syndrome and, according to Madaleno, credited him for making the Adams family aware of a condition that may have gone undetected twice.

“I didn’t save the kid’s life,” Madaleno said. “I just made sure they emphatically knew the seriousness and that we weren’t going to tolerate him being up here, going from one doctor, to another, right in the middle of a condition.”

A receiver that isn’t receiving

Becoming a better receiver isn’t easy when you can’t catch a ball, especially when you’re not allowed to. Playing football was second nature for Adams, but his physical activities were limited for the six months following his surgery while he remained on blood thinners.

“If I got hit with a ball or anything, it could’ve caused a bruise. Because I was on blood thinners, blood would’ve rushed to the spot,” Adams said. “Too much blood and it would have clotted, and I risked dying.”

The treadmill, stationary bike and elliptical machine became his best friends. When he wasn’t performing these tasks, he studied game film and prepared for class. Aside from the on-the-field activities he was missing, Adams couldn’t really bond with teammates. Naturally, Adams wanted to get back in the fold immediately.

“He was begging me to bend the rules,” Madaleno said. “I was learning the Brian Adams that I had encountered earlier was really the Brian Adams that isn’t going to go away. He has that kind of drive.”

‘All-American’ pedigree

By late December 2009, when specialists in Georgia and then team doctors at UK cleared Adams for physical contact, he knew he was going to make up for lost time.

Adams, who believes he would’ve played his first year had it not been for the clot, has zealously competed since his return. Wide receivers coach Tee Martin said he is one of the three hardest-working players he’s ever coached.

“He’s one of those guys that you can trust to be there on time, guys that you can trust to bring it every day, and I think that is why they have a high level of expectation from themselves and when things don’t work out they have a high level of frustration,” Martin said. “I like that about him, it shows that he cares about the outcome of what he’s doing and that he’s going to work hard until he gets it, and in the end, it’s going to make him a great player.”

Though Adams is still a raw talent after playing quarterback in high school, Martin said he has been pleased by Adams’ progression and that his athleticism, including 4.4 40-yard dash speed at 232 pounds, can compensate for his lack of understanding about some of the nuances of his new position.

“I’m always hard on myself. I like to be hard on myself, that’s how I get better,” said Adams, who has to be constantly reminded by Martin to not get too frustrated for occasionally making a mistake.

During film study, Martin said he routinely points to Adams’ play, even if it’s on special teams where he’s running down the field “hollering and ready to crash something,” as an example of the kind of effort his teammates should emulate.

Freshman quarterback Ryan Mossakowski, Adams’ roommate and good friend, attested that his work ethic goes well beyond football. Mossakowski said when dirty dishes pile up at their home, Adams will go on a neatness “rampage,” doing the dishes and then cleaning the entire house.

“We joke around, that Brian Adams is All-American,” Martin said. “He’s an American, he’s going hard, he’s going to get it the hard way and he doesn’t want you to give him anything.”

Not surprisingly, the “All-American” continues to play America’s pastime.

Adams kept his commitment to UK football after being drafted in the 45th round by the Cincinnati Reds in the 2009 Major League Baseball draft. But he’s now also a standout on the UK baseball team.

When UK baseball coach Gary Henderson heard Adams had a desire to play baseball, he didn’t hesitate to put him on the roster. After spring football concluded, Adams became a surprise starter in leftfield, starting the last eight games of the season. He appeared in 18 games, batting .472 with one homer and eight RBIs.

“Because he had to sit out for football, I think he was grateful for the opportunity to compete more than anything,” Henderson said.

As long as Henderson and UK head football coach Joker Phillips don’t mind to continue to share a player, Adams foresees playing both sports as long as he can.

“If it’s spring, I’m liking baseball, and if it’s fall, I’m liking football,” he said.

A love of the game, a love of life

If it’s not his blazing speed, dual-sport ability, or noted work ethic that separates Adams from his teammates, it’s the perspective he’s gained early in his college years.

“He’s had that feeling of not having something that he loves,” Martin said. “I think he appreciates what he has more so than a lot of the other guys because he was sitting there not knowing if he was going to be able to play.”

To date, Adams has made only one career reception. That doesn’t matter. The opportunity to start his football career with a clean bill of health is something to cherish enough for now. After all, there’s no telling how long it could last.

“It can be taken away from you in one play, you’ve got to enjoy every rep and enjoy it like it’s your last one,” Adams said. “It’s a great experience that God is letting me be back out here and doing what I love.”