Checkpoint: What does a reopened semester look like at mid-term?

October 13, 2020

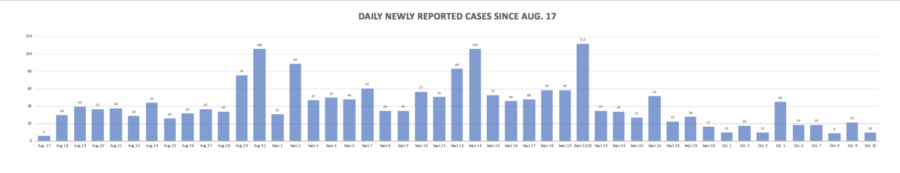

This week marks the halfway point of the semester, with eight weeks of an unprecedented semester in the books. Prior to UK reopening, college towns around the country braced for an influx of COVID-19 cases brought in by out-of-town students and perpetuated by poor social distancing. In August, that idea was born out by data from the Lexington-Fayette County Health Department. Upon students’ return, cases in Lexington increased.

The highest weekly total among UK students occurred after two weeks of classes, a predictable spike born out by incubation periods. Another predictable spike came two weeks after Derby Day and Labor Day, tying the earlier record of 371 weekly cases.

However, cases dropped in the first two weeks of October, which was somewhat of a surprise considering the rash of parties that occurred as football season began. Thus far in October, the average of new daily cases among UK students is 18, according to data from LFCHD. The number of total cases among UK students has plateaued for the moment, though daily cases continue to see small bumps every 14 days.

UK is without question the main contributor among colleges in Lexington; UK students account for 91 percent of all college cases, with the other four colleges included in the health department’s reports totaling 228 cases altogether, compared to UK’s 2,808 cases (1,977 this semester). As of Oct. 10, UK student cases since Aug. 17 equaled 21 percent of all of Lexington’s cases since March. Daily new cases among UK students average 37 percent of new Lexington cases according to data from the last month.

However, the rate of infection is slowing slightly. It took 23 days for UK to accumulate its first 1,000 student cases of the semester, a milestone the university hit on Sept. 23. It took another 31 days to hit the 2,000 case-mark, which occurred on Oct. 13.

UK and Lexington

One of the big questions heading into the semester was how a college population would impact a city’s attempts to control coronavirus. And although university reopenings are an economic boon to college towns, the data shows that UK students contributed significantly to case increases for the surrounding community.

September was a record month for COVID-19 cases in Lexington and Fayette County, with 2,808 cases accumulating over the 30-day period.

Cases among UK students contributed greatly to the high totals; 1,286 cases among UK students were reported by LFCHD in September, which equates to 46 percent of the city’s September total.

With such high totals for the city and UK, Lexington spent much of the month in the critical red zone, according to the state Department of Public Health. That red zone rating triggers certain restrictions, such as no in-person learning for public schools.

Fayette County Public Schools were thus very concerned that cases among UK students would prevent K – 12 students from going back to school.

Debate had previously surfaced over whether or not university cases should be considered when making decisions on a community level; no college has implemented a “bubble” type reopening, but the exact level of mingling between students and community members is unknown and, without strict surveillance, difficult to quantify.

According to the midterm report published by UK, only 5.5 percent of the close contact exposures reported to the UK Health Corps were not members of the UK community. The remaining 3,800 people contacted by UK Health Corps were Close contact is defined by the university as 15 or more minutes in maskless, close proximity to someone who has tested positive for COVID-19.

Gov. Andy Beshear said at his briefing on Sept. 24 that university cases must count as part of community spread because college students interact with the community through places such as restaurants and bars.

“If UK stays open and continues to have those amount of cases, it could potentially keep it red, and then you’ve got FCPS saying, ‘wait, we need a community spread that is low enough to where our kids can go to school’,” Beshear said. “That is a real issue.”

Beshear said he talked to both Lexington mayor Linda Gorton and the superintendent of FCPS about the issue.

“This also makes us rise up, elevate our thinking that it’s more than just the institution or institutions we serve, it’s the communities around us that can be impacted,” Beshear said.

Beshear had previously stated that UK’s factors for triggering a shutdown were unsuitable, since critical care capacity and hospital preparedness are not commonly necessary for college-aged people who contract COVID-19.

One concern from the city was off-campus partying, which led to a joint Lexington police/UK police patrol on weekends. UK spokesperson Jay Blanton said the university has 84 cases of student misconduct tagged as “off-campus” and “gathering.”

“One of the issues we’ve had early on with reports was the lack of complete information – such as addresses or names of participants in an event – so it wasn’t always easy to move the incident onto a more formal hearing,” Blanton said.

UK has issued five interim suspensions for student conduct this semester, Blanton said, which is a suspension awaiting a disciplinary hearing.

Was reopening a one-way street?

When UNC-Chapel Hill shut down just a couple of weeks after reopening, it seemed like the proverbial domino signaling the downfall of the pandemic semester dream.

Colleges continued to welcome students back anyway, and as time went on the likelihood of similar shutdowns decreased. This determination to stay open was aided by epidemiological experts, who warned that sending students home after any period of time on campus would cause a surge of cases as students brought the virus back to their hometowns.

On NBC’s TODAY show, Dr. Anthony Fauci called such a dispersal the “worst thing” colleges could do.

Dr. Deborah Birx, the nation’s coronavirus response coordinator, gave a similar warning to governors in a September conference call.

“Sending these individuals back home in their asymptomatic state to spread the virus in their hometown or among their vulnerable households could really re-create what we experienced over the June time frame in the South,” Birx said, according to NBC.

These warnings, which came a few weeks after most colleges reopened, became further fuel to the idea that, now that colleges had reopened, the best option was to remain open. But it’s important to note that sending college students home was always going to be a problem, whether or not universities shut down because of an outbreak.

Coming to one city and then leaving to go back home is the foundational structure of the college semester; students are eventually going to go home, and the question of how best to manage that transition should have been a priority from the start — not a potentially disastrous prospect that scientists and universities suddenly found themselves faced with a few weeks into the semester. The timing of this concern lends itself to the interpretation that colleges are using this dispersal fear to remain open, regardless of safety on campus.

As the semester progresses, a shutdown at UK becomes increasingly unlikely, not least because the university is reluctant to commit to a threshold for such an action. However, at this point the benefits of a shutdown are minimal, excluding a catastrophic outbreak on campus.

A multitude of factors contribute to this diminishing-returns phenomenon. For starters, the actual student population would not be greatly reduced if campus were to shut down. According to UK spokesperson Jay Blanton, only around 6,500 students live on campus. 25,339 students are coming to campus this semester, meaning that around 19,000 students live off campus, likely in apartments. Even if UK were to pivot to fully online learning, these students would most likely remain in Lexington because they are tied to their leases and possibly jobs. Also, remote learning does not necessitate de-densification of campus; students might be allowed to remain in their dorms even in the case of a shutdown.

A move to only online classes would likely not lead to a significant increase in cases anyway, since students are — for the most part — following social distancing protocols, including wearing masks, in classrooms. Transmission of COVID-19 is happening far less in the classroom than it is happening at any kind of gathering — even small ones — or in apartments, dorms, or through everyday contact at restaurants, jobs and with relatives. Those exposures would continue regardless of a campus shutdown or move to remote learning.

A shutdown of the campus and subsequent move to remote learning might trigger a loss of the community measures sponsored by UK, including free and voluntary testing for students and contact tracing. At least with the campus open, cases of COVID-19 among students are being reported and tracked in one county, a public health benefit that would be reduced if students were scattered around again. All students have access to testing, isolation spaces and campus Wi-Fi, all of which help bridge the economic gap that emerged during online learning in the spring.

In the long run, staying open even as cases rise benefits the university because we are on a faster track to herd immunity. According to LFCHD, 2,208 UK students were reported as having had COVID-19 since March; 70 percent of those cases were reported since the beginning of the reopened fall semester on Aug. 17. Although the science is shaky on how long immunity lasts and epidemiologists differ on what the threshold for herd immunity is, at this point nearly 10 percent of UK students (nearly 3,000 out of 30,000) have had COVID-19, a greater percentage of the population than other demographics are seeing. This estimate does not include students from out of town who contracted COVID-19 over the summer and were included in the statistics for their local health department.

All of these relative benefits seem to reinforce the idea that reopening was a good idea; however, they only become benefits once a campus is open and infection spread is underway. Did colleges know this, and reopen knowing that once students were back no one could argue against keeping them on campus? We will never know. We will never know if UK reopened solely for profit; despite repeated assurances that safety is the driving force behind the university’s decision, the fact remains that the CDC’s guidelines say that the safest format for any education is online. But now that we are here, all signs point to staying here. We have already stayed open with 400 to 500 active cases at a time; it is difficult to imagine a higher threshold that would trigger a shutdown. Campus shutdowns were the default mechanism in the spring, but even with cases rising in Kentucky and across the country a similar shutdown in the fall is increasingly unlikely.