A tale of two pandemics

March 12, 2021

If you thought 2020 was bad, wait until you hear about 1918.

Still in the throes of World War I, a global conflict the likes of which had never been seen, a myste-rious new respiratory illness silently but steadily travelled through barracks. But while soldiers on the front lines and in training camps were the strain’s first victims, they were nowhere near its last.

Influenza was a skilled killer. It felled 14,000 Kentuckians, 675,000 Americans and 50 million peo-ple worldwide before it ran its course, according to the University of Kentucky’s 1918: Over Here exhibit, curated by UK librarians Carol Street and Jennifer Hootman.

The first known case appeared in March in Kansas at Fort Riley, where soldiers were training. Con-trary to popular belief, this disease likely did not originate in Spain, as the “Spanish influenza” nickname would have people believe. Wherever the actual origin, the strain was mostly contained within training camps and prisons until the end of America’s involvement in WWI in November 1918, when soldiers came home to huge celebratory events where influenza was disseminated.

But there were “superspreader” events before then – one of the most infamous in Philadelphia in September 1918. Despite calls from doctors and health experts to call the event off, the city held a massive “Liberty Loan March” to raise money for the war effort, according to a history.com article. 12,000 Philadelphians died from the flu in the following four weeks.

Gov. Andy Beshear alluded to Philadelphia’s mistake in some of his COVID-19 updates, instructing Kentuckians to be like St. Louis, which cancelled their 1918 parade, not Philadelphia. Hootman said that this contrast between pandemic approaches by different localities was one striking paral-lel between the two pandemics she has noticed.

Kentucky’s first case of the flu appeared mid-September at Camp Zachary Taylor, near Louisville, said UK Special Collections librarian Terry Birdwhistell. As the troops travelled along the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, they briefly stopped at Bowling Green, spreading the disease in the process. By November, the state had 8,000 cases. By mid-December, the health department was so over-whelmed they asked Surgeon General Rupert Blue to have the U.S. Public Health Service take over all other administration of health work business until the pandemic was over.

Louisville was hit hardest. Within a week of the first reported contraction, there were 1,000 influ-enza cases. Approximately 180 people died from the flu during both the second and third weeks after the initial case.

The Kentucky State Board of Health announced an order to close “all places of amusement, schools, churches and other places of assembly” on Oct. 6, along with a travel ban, according to a Courier-Journal article.

Lexington, a more rural community at the time, staved off influenza a little longer. The city experi-enced its first influenza casualties on Oct. 10; William Wade, 47, and Francis Arnet, 14, according to the Lexington Herald-Leader. Just one day later, UK president Frank McVey announced that the university would close for a month, and the Buell Armory would transition to a makeshift hospital for students run by the American Red Cross.

Influenza had entered UK’s campus through the Students’ Army Training Corps’ (SATC) ranks, a group of about 400 men who prepared to fight for the war effort in Buell Armory. Throughout their train-ing, 170 members fell ill and five died from the flu, including sophomore Private Harry K. Smith of Louisville and freshman Private G. Lloyd Haydon of Springfield, Ky.

Preceding the October campus closing, two functions contributed to the spread—an Oct. 1 natural-ization ceremony, where 1,100 men were inducted into the U.S. Army and Navy, and an Oct. 5. circus-themed party hosted by the Philosophian Society in Patterson Hall for female students. However, after the quarantine order, students mostly avoided future gatherings, likely due to a real fear that getting sick might actually kill them.

“We have so many ways to treat this disease. And even then, we’ve seen over half a million deaths nationwide,” Birdwhistell said. “When you got sick, back then the treatment was really much dif-ferent than you would have today.”

Among the 1,200 students enrolled at UK in 1918, 403 contracted influenza and eight died. It could have been much worse, Birdwhistell said. UK’s death rate was lower than the state as a whole, making them a model for other communities to follow.

“I think one of the parallels is that it took leadership from the university to make sure that we got through the (pandemic) in 1918 and also the one now,” Birdwhistell said. “Not unlike now, it took a community effort, you know, everybody pulling in the same direction.”

In 1918, the community was led by McVey, who had only been at UK for a year before the pandemic hit. He came from a presidency at University of North Dakota with a Yale doctorate and a former professorship and public policy experience at the University of Minnesota, which guided him along his journey to solidify the shaky financial standing of the university at the time. He made the tough decision to shut down campus from Oct. 11 to Nov. 3 for everyone but SATC members and a hand-ful of women residing in the Maxwell and Patterson dormitories.

Those five weeks of halted instruction may have saved lives, although it did delay commencement an additional month. Birdwhistell said that he thinks UK is lucky to have Capilouto, with his public health doctorate, as president this time around.

In 1918, UK tried and failed to keep students on campus for the entire fall semester. But in fall 2020, it was a different story.

“I think that the effort that UK made on behalf of students, to try to get students back on campus, try to get things back as normal as they could, was really took a huge effort and it was kind of a gamble, in a way, to see how that would work out,” Birdwhistell said. “From my perspective, that seems to have done about as well as could be expected.”

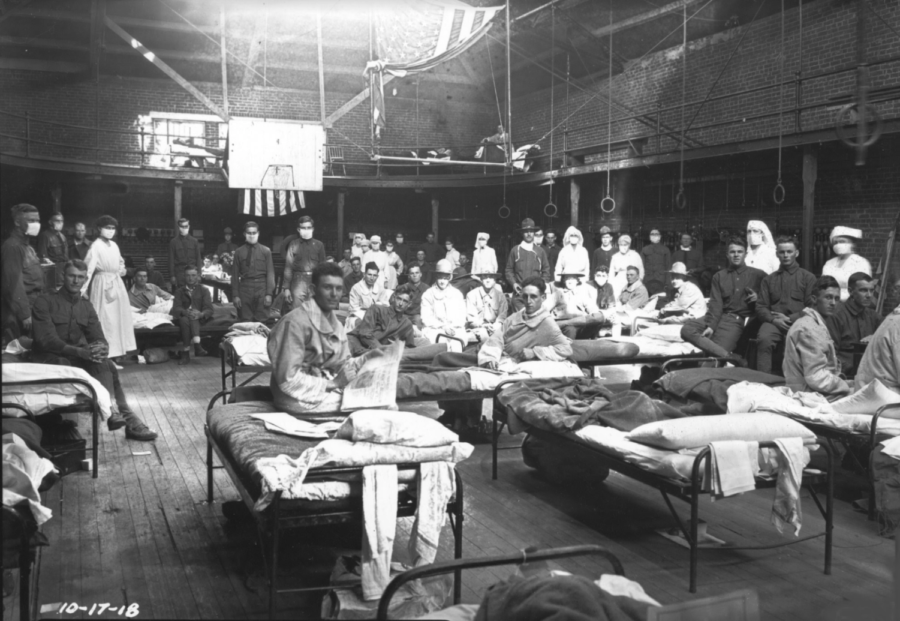

Another key sect of the community effort against influenza was the group of women who ran Buell Armory, the campus gymnasium turned makeshift hospital. Mrs. George R. Hunt led the Lexington chapter of the Red Cross, Mrs. W.H. Thompson managed the hospital, Miss Catherine O’Brien was head nurse and ten female staff took charge of nursing duties and food preparation. According to a Nov. 11 edition of the Kentucky Kernel, the hospital could accommodate 150 students at a time, and was a major success.

Street said that looking at photos of these 1918 frontline workers, often wearing masks, was very familiar.

“They looked exactly like the faces of the hospital workers we see on the news reports every night, just with modern clothes,” Street said. “I understood why they look the way they did. They look tired, and they looked exhausted and as they’ve been working all day and dealing with something that they’re really scared of and worried about taking it home to their families.”

One of the most tangible long-term effects of the 1918 pandemic on UK came out of this medical endeavor. At the December Board of Trustees meeting, members suggested that the university needed a permanent hospital on campus. This conversation began a multi-decade push that result-ed in the 1962 opening of Albert B. Chandler Hospital and the beginning of the UK HealthCare en-terprise.

Over a century ago, antsy quarantiners didn’t have Tiger King, Chloe Ting workouts or TikTok to keep them occupied. But that didn’t stop them from having a little fun. The fifteen women stuck in the dormitories during the five-week break in classes found many activities to occupy their time, as reported by the Kentucky Kernel:

“Rare friendships have developed among the girls who now realize that the only reason why many people don’t like each other better than they do is simply because they don’t know each other. The girls embroidered, knitted, played cards, danced, took long hikes, read countless books and stories, sang and serenaded until they either lost their voices or became professionals, accumulated quite a collection of snapshots, almost wore out Mary Archer Bell’s victrola, stole a ride in Elizabeth Kimbrough’s Ford, and played many games…”

Street said there were some examples of mask resistance from 1918, but not many on campus or in Lexington. Their research for the 1918: Over Here exhibit didn’t find whether or not the limited resources and communication tools people had in that time period, with newspapers as one-way gatekeepers of information, contributed to the milder resistance. Hootman added that staying at home might not have been as big of a deal, considering that the economy didn’t rely as much on restaurants and businesses as it does today.

“It seems like there are sort of cavalier attitudes today about widespread virus,” Hootman said. “’Oh, it won’t touch us, we don’t die from these different kinds of things today,’ you know, like in previous generations, but we do. We do die of these sort of pandemics and epidemics all the time, not only in this country but around the world.”

The Kentucky Kernel wrote an op-ed to students stuck on campus on Nov. 27, writing that while Thanksgiving looked different in 1918, with war and influenza, they could still find reasons to be thankful.

“The flu will probably be raging, and perhaps some other destroyer of happiness will have been discovered by that time, but our thanksgiving must not cease,” the article read. “Those who ha-ven’t the flu, be glad you’re escaped, and those who are unfortunate enough to have it, be glad you’re not dead.”

It’s unclear whether the level of compliance with quarantine orders really was greater in 1918, or non-compliance simply wasn’t recorded. Nobody could Tweet out an infraction of the pandemic rules in 1918, Birdwhistell said, and if, say, church congregations in rural areas continued to meet, there was little to no enforcement.

When students returned to class, they faced new protocols, similar to this spring’s campus return. According to the Kentucky Kernel, those who left campus needed to obtain a doctor’s note from their county or town health authorities verifying that they hadn’t been exposed to influenza in the past four days and have permission from the Lexington Board of Health to return. When they ar-rived, they were under a four-day quarantine before they could resume their studies.

“The welcome of fellow classmates, who have (escaped) or recovered from influenza, will be en-thusiastic this first week; each will be eager for the work which awaits him after almost five weeks of interrupted classes and the waiting studies will be seriously (attacked)” read a Nov. 11, 1918 Kernel article headlined, “Flu Well in Hand.”

Things quickly returned to normal the spring of 1919, Birdwhistell said, with classes and sports back on track. Football fans were among the most ecstatic. The loss of most of the 1918 football season, save three games, was perhaps almost as big a disappointment as 2020’s sports cancellation.

Before the Board of Health order, UK’s only competition was their season opening victory at Indi-ana on Oct. 5. Their annual Thanksgiving match against rival Tennessee was canceled, along with the postponement (and eventual cancellation) of a match against Centre, who was particularly upset at their lost chance to defeat UK for once.

“For the first time in years the Wildcats can eat their turkey in peace, with no thoughts of a coming gridiron struggle, and townspeople with the lure of the pigskin removed, can observe the day with true Puritan tranquility,” the Kentucky Kernel reported.

The football squad, made up of SATC members, played two other games on only a few days of prac-tice: a loss at Vanderbilt on Nov. 2 and a win at Georgetown on Nov. 9. The 2-1 record was disap-pointing for all involved, but the 1919 Kentuckian, UK’s yearbook, chose to look at it from a hu-morous standpoint:

“There are just two lenses through which to look at that gridrion record. One is lettered S.A.T.C., the other FLU. In roughneck parlance, if such will be pardoned, ‘S.A.T.C. and flu sho’ busted up Kentucky football last fall.’”

Throughout the 1918 pandemic, Fayette County had roughly 1,000 influenza cases and 51 deaths, according to the Lexington Herald-Leader. The death count could be underreported due to the misclassification of some influenza deaths as pneumonia deaths. With a population of 41,000 peo-ple, that’s a 2.4% positivity rate and 0.1% death rate.

So far, there have been 32,789 Covid-19 cases in Fayette County, as well as 234 deaths. With a population of 322,000 people, that’s a 10% positivity rate and a 0.07% death rate.

If one were to just look at these numbers, it would seem that Lexington has learned from history. But is it a fair comparison?

“I think the ways we had of dealing, I just think it’s like apples and oranges in a way,” Birdwhistell said. “Look at this one today—how many more people are in the country? How many more people are in our communities? … It’s is just different times and I think it took different strategies this time and we’re not out of it yet.”

One key similarity between 1918 and 2020 is that both begged the question of how much can so-ciety bear at one time. In 1918, influenza was far from the only issue on the table. There was the massive destruction of WWI, racial issues, economic changes and influenza, Hootman said. In 2020, there was racial strife, a hotly contested election, economic problems and wildfires, in addition to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I got the sense like in doing our research for 1918, that the flu pandemic, I mean, while it was really awful, it wasn’t their biggest focus of the year,” Hootman said. “It really seemed to me the war was the big focus.”

Perhaps the most interesting connection, however, is the use of humor to cope with adversity. In 2020, people all around the world used social media to joke about their experiences in an attempt to make light of the situation. While they didn’t have TikTok or Twitter in 1918, they weren’t lack-ing in humor, as illustrated by this entry in the 1919 Kentuckian:

“Flu—like hair, most every one has it. God bless the bald-headed man.”