Are the Oscars a waste of time?

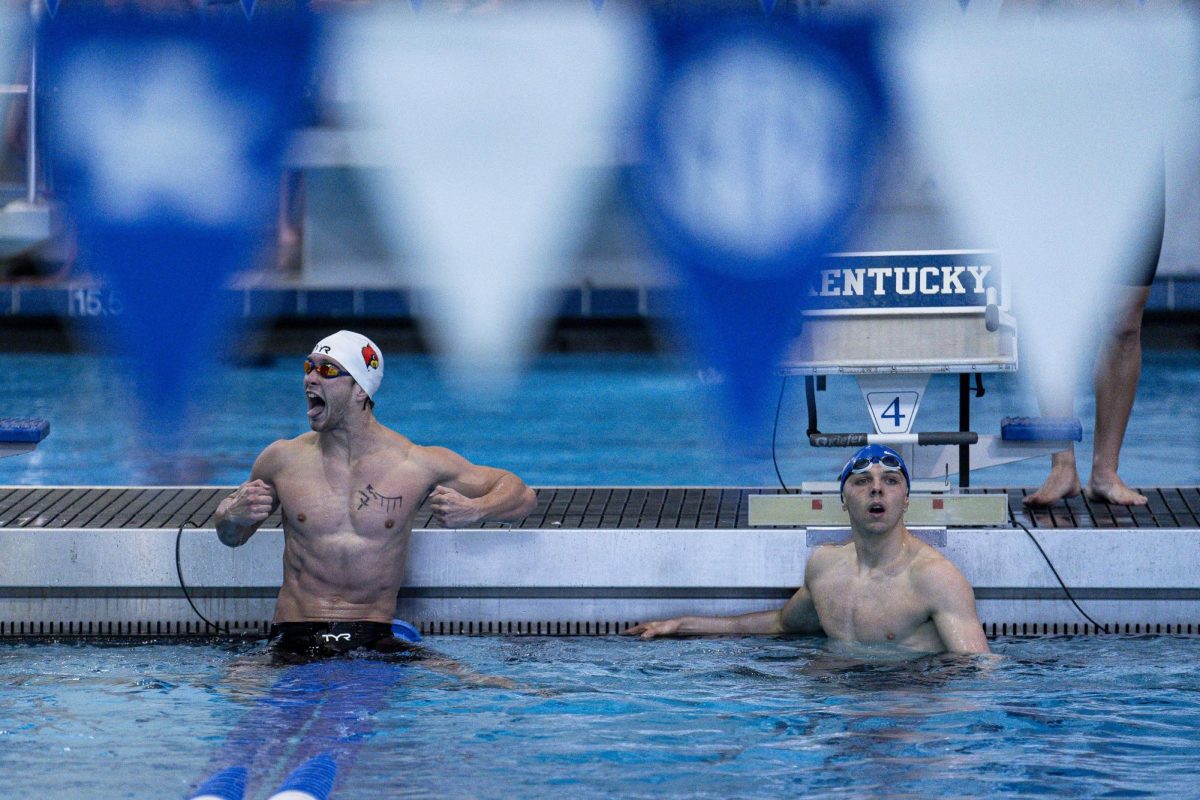

Alejandro G. Inarritu accepts the award for best director for "Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)'', in the press room of the 87th Academy Awards on Sunday, Feb. 22, 2015, at the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood. (Ian West/PA Wire/TNS)

February 25, 2021

I typically find out the Oscars are happening the day after they’re over. Same with the Golden Globes, Emmys, Grammys, Tonys and the dozens of other awards shows usually broadcast at the beginning of each year. The truth is, I don’t think they are worth either my time or yours.

While it’s indisputable that many great films have won the Oscars’ Best Picture—Spotlight, Slumdog Millionaire, Forrest Gump—just as many awards show victors miss the mark. For example, one of my closest friends went to the movie theater with her family to watch 2018 Best Picture, The Shape of Water, and was shocked at how much she hated it. After all, it had won what is arguably the most prestigious award a film can receive. But she said the movie was weird and over her head and overall, not good.

Of course, everyone has a different opinion. But there seems to be a pattern in which the films chosen for Best Picture seem a lot like the “try-hard” students in high school English who try to make everything artificially deep and profound to impress the teacher even when it’s completely unnecessary. Yes, those students might turn in good essays, but they rarely write the most captivating or genuine or entertaining essays that I would classify as truly great.

A great movie shouldn’t confuse half the audience or only be appreciated by filmmakers; it should be accessible and have widespread appeal across many demographic groups. The movie that wins the Oscars’ Best Picture should be like the English essay that would win “best essay” if everyone in the school voted on it, not just the experienced and knowledgeable English teacher.

And then there’s the diversity issue. The Academy can’t honestly expect us to believe that out of the hundreds of films, directors, actors and screenwriters that could win an award, white creators, particularly men, deserve almost every one.

A 2021 Insider magazine investigation found that in the past decade, white creators received 89 percent of the Academy’s nominations for the top eight Oscars’ categories: best picture, best director, best actor and actress, best supporting actor and actress, best original screenplay and best adapted screenplay. In addition, men got nominations over women 71 percent of the time.

There is no excuse for this. It’s alright if a person of color or female doesn’t win Best Actor or Actress every year, but there is no reason they shouldn’t be well-represented within the nominations. If the Academy has 100 films or actor nominations to choose a winner from, and only 11 are POC and 29 are women, those groups aren’t going to get their fair shot.

Ever since the 2015 Oscars, when people began speaking out about the diversity problem, there have been efforts to improve. But until it’s clear that the Academy’s changes aren’t simply performative, but are actually making a significance difference, there’s little chance I will be tuning in to the show.

Speaking of performative activism, many of the acceptance speeches at the Oscars are all too reminiscent of the celebrity rendition of “Imagine” at the beginning of quarantine—all talk, no substance. Of course, being the kind of person who only sees the highlights the next day, I may hear more about the tone-deaf speeches trending on Twitter than the better ones, so this may not be an entirely fair assessment.

So, what’s the solution? First, the Academy should look into its voting members and adjust for diversity. If an overwhelming majority of the voters are white men, then the Oscar winners only reflect one perspective.

Second, the Academy should find a way to make sure Academy members are actually watching the films they are supposed to be choosing between. According to a Vanity Fair article, some voters neglected to watch certain films they didn’t consider Oscar-worthy, like Get Out, or ones they didn’t anticipate liking, like Little Women. The best decisions can’t be made without all of the information, therefore dismissing certain films or actors/actresses without even giving them a chance is unacceptable.

Third, the Academy should find a way to include the public’s opinion of a film, actor/actress or screenplay into their consideration of nominations and eventual winners. Maybe, the public can vote during a certain period and their opinion can be weighted as 10 or 20 percent of the final vote, with the normal Academy members’ votes making up the other 80 or 90 percent.

Moviegoers don’t want to watch an Oscar film only to ask themselves afterward, “Really, this won the Best Picture?” They want captivating, entertaining and representative winners, and the Academy should give that to them.