Caught between two homes

February 2, 2017

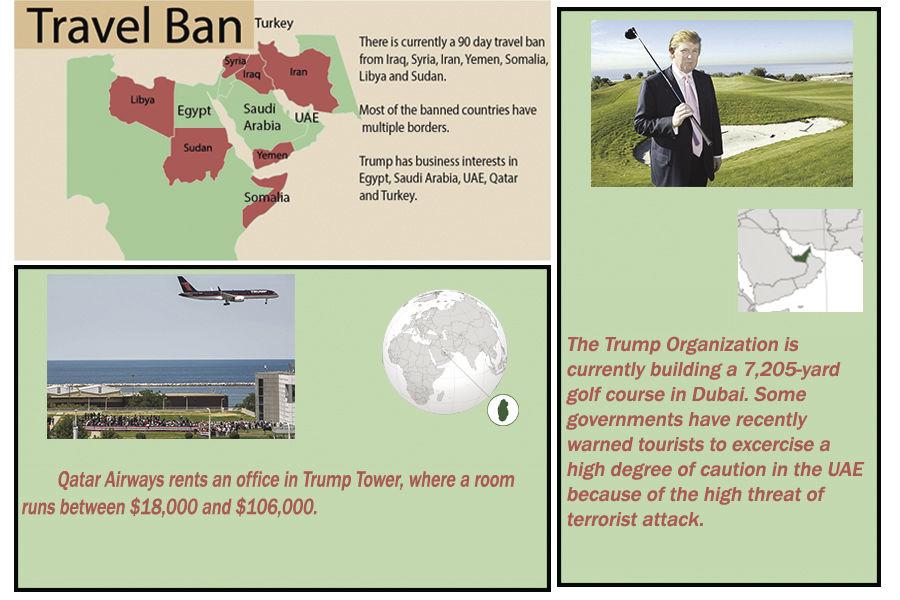

On Jan. 27, Trump signed an executive order that halted the issuance of visas, barred refugees, and detained immigrants and citizens traveling from Syria, Iraq, Libya, Iran, Sudan, Somalia and Yemen.

Universities across the country, including UK, have issued formal statements in regard to Trump’s executive order, and advised students not to leave the country.

Foreign students across the country are worried whether they will be able to continue studying in the U.S. and if they will be able to renew their student visas.

“Family is much more important than cancer.”

Amin Abedini is battling bladder cancer on his own, while his wife, stuck in limbo like many other immigrant families, is in Iran barred from re-entering the U.S.

He received the diagnosis while she was in Tehran helping her father recover from heart and brain surgery.

They came to the U.S. hoping to honor his mother’s dream to see all nine of her children become successful. With three PhDs, one medical doctor, a mayor and three master’s graduates under her belt, Abedini’s pursuit of a PhD in mechanical engineering in the U.S. will fulfill that dream.

“My mother is a wonderful woman who believes that higher education is the key factor for her children to be beneficial to themselves and society,” Abedini said.

That dream may be interrupted if his F1 student visa expires before the government lifts its ban on issuing visas, and he is deported back to Iran.

Through all of this struggle, the least of his concerns has been his health.

“I think my family is much more important than cancer,” Abedini said.

Abedini hasn’t been able to see his family since he came to the U.S. in August of 2015 because his visa does not permit multiple entries. He has no family in the U.S., and the newlyweds have had little time to begin their life together here.

They married three weeks before moving to the U.S. and she had to return five months in to help her ailing father. While abroad, she secured a multiple entry visa and booked a return ticket for Feb. 4. A week earlier and she would have been able to take her husband to his appointment this Tuesday, where he will learn more about his condition.

“It’s really devastating to see all of your desires, ambitions, achievements and plans suddenly turn to ash,” Abedini said.

Abedini said he knows the world is not black and white, and believes the majority of American people are caring and welcoming. He believes the country has the potential to accept immigrants, and with them utilize their skills and expertise.

“In almost all countries when the politicians can’t fulfill their promises and objectives, they try to put the blame on an external cause,” Abedini said. “I think it’s better to think about the root causes which generate refugees. Refugees themselves are victims of these root causes.”

“Iran is a piece of me.”

Parisa Shamaeizadeh thought the travel ban was a bluff. She said she couldn’t believe that a president would force an order that would fragment families like hers, which is now split between two countries.

“After he signed it and I heard about everything that was going on in the airports, I was shocked and disgusted,” she said. “It hit me like a brick.”

As a dual-citizen of Iran and the U.S., she doesn’t know if she would be able to return to either if she tried to travel.

“My biggest fear is that it will become permanent instead of temporary,” she said. “If not permanent, it will scar relations to the point that I can’t go back to Iran or my family will never be able to come here.”

She was born in Prestonsburg to an Iranian father, and has spent her life traveling back and forth between the states and Iran to visit her family. After her grandmother was unable to get a visa to visit her newborn grandson, Shamaeizadeh’s fears manifested into reality.

“Because of the political tension… and because of this ban, I probably won’t be able to go this summer to see my family. It’s separating me from them.”

Shamaeizadeh said she is scared she will not be able to take her future children to visit Iran and to experience the culture if the travel ban stretches longer than the allotted time, or if it becomes a permanent fixture for U.S. travel laws.

“The first time I went to Iran, I fell so in love with it because it’s so historic, so beautiful and the people are so kind. It’s a culture you can’t find anywhere else.”

“I’m literally stuck here. At least for now.”

Ranym Nenneh is alone in Lexington. Her mother and grandmother are in Damascus, Syria. A few days ago, that meant she was only a plane ticket away. Now she fears a trip would risk her education at UK, or worse a secure refuge from the conflict in her home country.

Nenneh was born in Cairo, Egypt and raised in Damascus. She moved to Lexington on an F1 student visa in August 2014, and is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in psychology and business management.

She has called Lexington her home for the past three years, but said she now feels unwanted in a place that used to be her community because of the increasingly negative attitude towards foreigners.

“It concerns me that this order reflects a general hostile environment towards foreigners in general, and citizens of the seven concerned countries in particular,” Nenneh said. “It makes me feel unwanted, and Lexington no longer feels like my second home.”

With the support of friends, coworkers and professors during this confusing time, she said she is reviving her hope in the American people.

“It gives me hope that the American people are all about support and inclusion, which gives me back a sense of safety and comfort,” she said.