After hearing proposals, committee still deciding what art to add to controversial Memorial Hall mural

May 15, 2018

After numerous debates and discussions, the UK Memorial Hall art committee made the decision to incorporate another artwork into the historical building to add context to Ann Rice O’Hanlon’s 1934 mural.

The committee was created in February 2016 as a response to a meeting between UK President Eli Capilouto and African-American students held in late 2015.

The decision to add more context to the mural was made by the committee in September 2016, and in March 2018, two acclaimed artists, Karyn Olivier and Bethany Collins, came to UK to present their proposals for an additional art piece. The committee has not yet made a decision.

The Maxwell Place Discussion

On Nov. 12, 2015, a group of 24 African American students were invited to have a discussion with UK President Eli Capilouto in his home on Rose Street.

“They did not feel included, they did not feel welcomed,” said UK Assistant Vice President for Institutional Equity Terry Allen.

The group of students presented a list of 18 recommendations to better the inclusion of UK’s campus. Number 14 was about the mural in Memorial Hall– which they considered racist.

“The image sanitized the treatment and brutality that existed through the course of slavery and legal segregation and legal discrimination,” said Allen.

Quiyana Murphy, a recent graduate with majors in mathematics and psychology and a minor in political science, was invited to the meeting as president at the time of Alpha Kappa Alpha, a historically African-American sorority.

Murphy said that the mural depicted an inaccurate history of slavery, and “now it’s time to take steps to understand this was a bad part of history that should not be glorified.”

After the discussion, Capilouto opted to cover the mural temporarily while a new solution was reached.

Capilouto announced the creation of the committee in 2016 to take the recommendation from the students and “provide an accurate and complete story and provide context for those who visit the building,” said Allen.

The Mural

Anne Rice O’Hanlon created the mural in Memorial Hall by invitation via Edward Rannells, chairman of the UK Art Department as part of the Public Works of Art Project.

The PWAP was established during the Great Depression as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Smithsonian website said.

The Archives for American Art stated that PWAP was created on Dec. 8, 1933, to give unemployed artists the opportunity to create artwork in nonfederal public buildings.

The mural was completed in 1934, five years after Memorial Hall was built.

The mural is considered to be “one of the only true frescos” in the country, the O’Hanlon Center for the Arts’ website said.

A fresco painting is created by applying colored pigments to freshly applied plaster. After the pigment has dried with the plaster, the artwork becomes part of the wall on which it was painted.

As the mural is a fresco, removal was not really an option. The mural has become part of the building and cannot be removed without destroying the artwork itself, said Stuart Horodner, the director of the UK Art Museum.

The mural will not be removed in the near future, if ever.

“The current option we are at now is the best possible step after that decision– to continue the story, create more context and tell more history,” said Murphy.

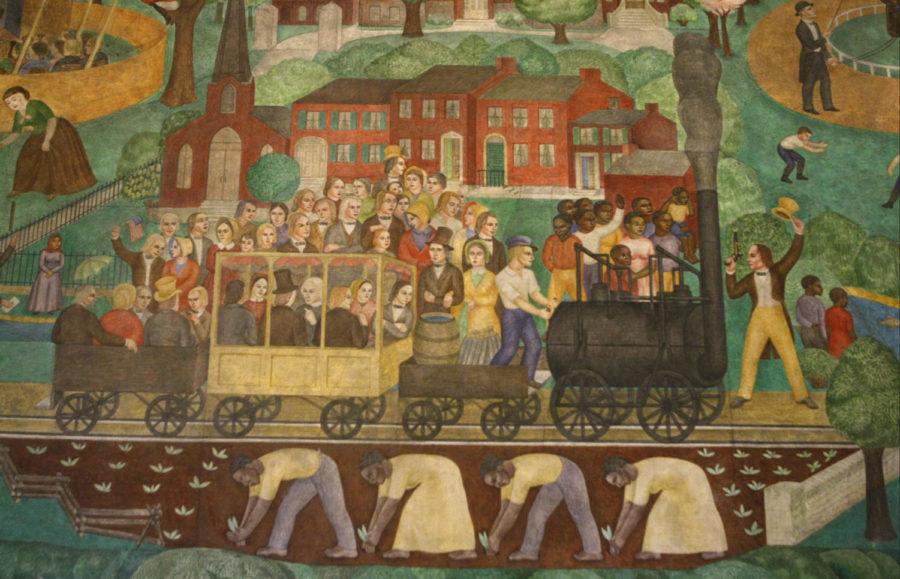

The mural is a complicated combination of ideologies and history.

“It has representations people find challenging. It also has representations of historic places, historic people. It is one person’s take on the legacy of this commonwealth. It is not the only story,” said Horodner.

Adding Context

After the meeting in Maxwell Place in 2015, Capilouto created the Memorial Hall Art Committee to listen to concerns about the mural and create a solution.

The committee includes:

- Terry Allen, Co-chair

- Stuart Horodner, Co-chair

- Jay Blanton, UK spokesman

- Anastasia Curwood, UK faculty in History

- Sonja Feist-Price, Vice President for Institutional Diversity

- Nicole Jenkins, Executive Associate Dean of Gatton College

- Allan Richards, Art Historian and UK faculty in Art

- Mary Vosevich, Vice President for Facilities Management

- Quiyana M. Murphy, student member

“The strong sentiment of the committee, after months of thoughtful discourse, has been to preserve this significant work of art for those on our campus today and for those who will follow tomorrow,” read Capilouto’s 2016 blog post.

The committee set up an email address so everyone on campus could submit their opinion about the plan for the mural.

“We wanted a process that was open, transparent,” said Allen, “a process where everyone could be involved. Every opinion would be taken seriously and valued based on the merit of the opinion itself.”

One of the first steps was to provide different information at the site, said Horodner. This included information about the mural, the artist, the history of the mural, frescos, some of the issues surrounding the piece and the action plan.

Then the decision was made to try to engage contemporary artwork that “might be in dialogue with the mural, might comment on the mural, might take a bigger picture and look at memorial hall and its history,” said Horodner.

The committee then created an open call for artists to create a proposal for artwork that would be placed in the vestibule of Memorial Hall.

The committee members were looking for an artist with ties to Kentucky as a remembrance to the original artist’s ties.

“Because the mural was created in the 1930s depicting the origins of Kentucky to the time it was created, the committee envisioned that the artwork would speak about the 1930s to the present and speak about the nature of Kentucky or America or race or representation, or those general concerns,” said Horodner. “We wanted something thoughtful, something intelligently conceived that had a connection to Kentucky.”

However, the first set of submissions were “very uninspiring to the committee,” said Horodner.

“This is important, we wanted to get it right,” he said.

The committee then personally reached out to multiple artists who they believed would be a good fit for the project, but they were again underwhelmed, Horodner said.

It was then suggested that Horodner, as the director of the UK Art Museum, propose three artists to the committee.

The three artists suggested were women of color, had nationally known artwork, and had works that deal with issues of history, race and representation.

Only two of the three artists that Horodner proposed showed interest. Karyn Olivier and Bethany Collins moved forward with their proposals.

The committee viewed the proposals and still had questions to ask and “thought it was very meaningful to bring them to campus to meet with people– stakeholders, students– and see the actual site,” said Horodner.

While both proposals were thoughtful, they were very different, Horodner said. This led the committee to decide that a site visit could be the “final layer” needed for the artists’ final proposals.

Horodner said he believes UK would be lucky to have artwork from either artist, but it is a bigger conversation.

“I hope this issue isn’t a ‘one and done’ solution. It’s an opening up and insisting that life is complicated. We don’t want anyone to feel consistently unthought-of or compromised,” said Horodner. “The challenges of generosity and respect are ongoing and my hope is the artwork contributes to that.”

The Artists’ Proposals

Karyn Olivier presented her proposal for artwork for the vestibule on March 20.

“I’m interested in artworks that can have a relationship to history that can make us reckon with the present, that can talk about the impact of the future,” she said.

She said she was interested in investigating O’Hanlon’s piece as a single perspective and “shed light on what’s hidden in plain sight in the mural.”

Olivier plans to recreate the mural in the vestibule, but in the eight instances where there are African-American figures, she plans to recreate those shapes in gold leaf, providing a “stark contrast to the white figures in the mural.” She also plans to have the “displaced” figures represented as they are in the original mural on the inside of the dome.

The use of gold leaf dates back many centuries, often used in sacred paintings and in sacred places.

“I hope my discrete use of gold leaf within this ‘contemporary’ mural will serve to elevate the oppressed represented-those who were deemed lowly-to the divine,” Olivier said.

Olivier said this piece is an extension of her practice.

“This an extension from the work I do– how do I show conflicting histories and how do we then see these histories and try to understand what does that mean for subjectivity, for my life,” she said.

She said her piece is not about solving, but about asking questions and “offering a space for discourse.”

Bethany Collins presented her proposal on March 29.

Collins is originally from Montgomery, Alabama, so “[her] work is very much rooted in the history and the memory of the south.”

Collins focuses on race, identity, history and language in her artwork.

“Language is often the subject of the work. It is the material out of which I am making… (using encyclopedias, dictionaries, and historical documents),” she said. “Language is not just the subject and the material, it is also a kind of prism through which I can interrogate any other topic.”

Collins plans to engrave the text of of two different documents into the walls of the vestibule, the Kerner Commission of 1968 and a page from the official report from the recent events of Ferguson, Missouri.

The two pages would be one from each document with most similarities to the other, she said. Collins wants the text to “speak to one another” but also “feel 50 years apart, while saying the same thing.”

“I realized that these, with 50 years separating them, are very similar reports– the analysis is similar, the recommendations are similar, and the inaction that followed is strikingly similar,” said Collins.

Collins’ idea for her art piece stems from O’Hanlon’s mural being a version of history, not one that is necessarily a complete or accurate version.

“What I’d like the reports, by showing them as you enter the space before you reach the mural, is to show a really brutally honest, truth-telling document,” said Collins.

Collins’ believes O’Hanlon was attempting to show the contributions of Kentucky on a national scale.

“That, though, was founded on enforced labor, on the contributions of those that did not necessarily want to contribute to Kentucky,” Collins said.

Collins’ piece would show “a kind of unflinching honesty” about how slavery still impacts us today.

Allen said both artists were “extremely interesting.”

“We are searching for art that will enable our students, our visitors, our faculty, staff, all of those who use this building, visit this building to give a particular frame of reference while they are on our campus,” he said.

The artists’ final proposals were due April 30, 2018. There has been no final decision by the committee; however, the members plan to begin the installation of the artwork in the coming months, according to Allen.

Progress

Frank X. Walker, Kentucky’s first African-American Poet Laurete and an English professor at UK, said in a previous interview with the Kernel that the mural was causing conflict when he was a student at UK in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Walker credits the current university leadership with the ability to progress with the mural in ways that past administrations had failed.

“[Dr. Capilouto’s actions] illustrate belonging, continues the conversation. Illustrates that the university as a whole has listened,” said Allen. “Of all the times the mural has been an issue, up until two years ago, nothing was different.”

Allen said that campus has a long way to go in terms of being able to progress as an institution of so many different people.

“This is a very small part of what campus strives to become, but it’s a very important part.”