UK supported evolution before it was cool

February 11, 2019

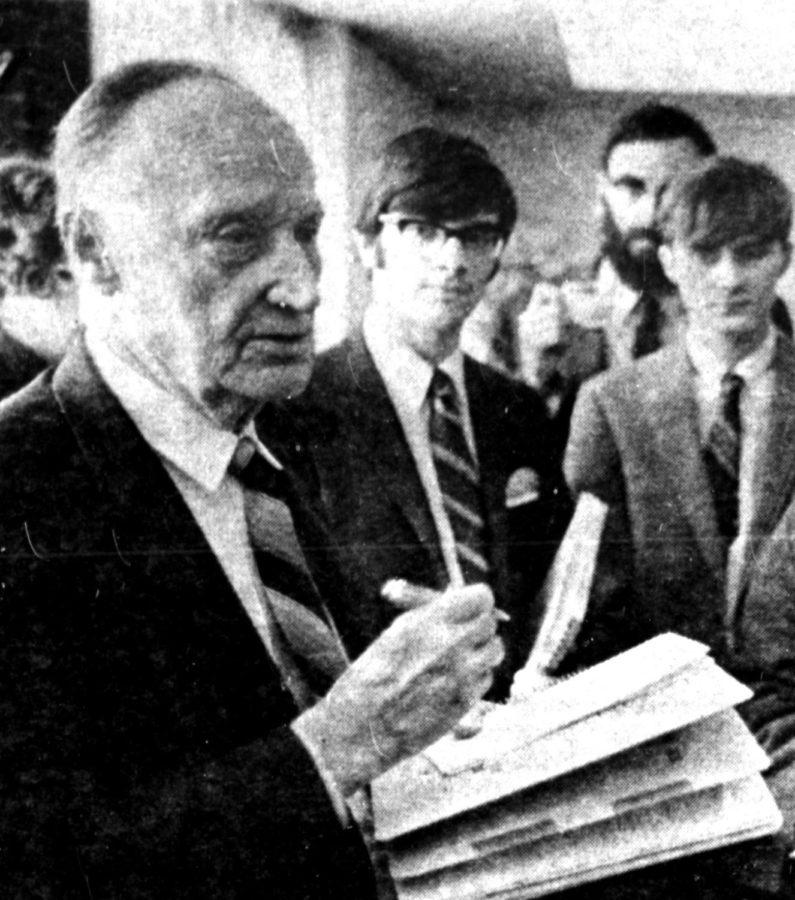

Retired UK professor Joseph Jones wants UK to remember its connection to a century-old American debate on the beginnings of all life on earth.

Jones recently created a plaque commemorating the university’s involvement in the evolution trials of the 1920s. The plaque, which was put up in Miller Hall in January, describes UK’s connections to resisting laws against teaching evolution in both Kentucky and Tennessee. A UK alum was even a prominent member in the famous Scopes Monkey Trial.

The idea for the plaque rose out of a talk Jones gave to a group called the Cricket Club.

Each month, a member of the club gives a talk about a topic of their choosing. Jones’ talk covered early confrontations between evolution and the law. But it wasn’t until Jones took some curious friends to the Creation Museum that he began to wonder what kind of legacy those confrontations had left.

“It was the Creation Museum that got me started,”Jones said. “I thought, people make fun of Kentucky because we have these two Fundamentalist gazillion dollar theme parks, but Kentucky was the state that defeated the very legislation that would have allowed that to be taught.”

The Creation Museum and the Ark Encounter are two attractions in Kentucky that advocate for seven-day creationism and Biblical literalism. They represent the insistent divide between Americans about evolution; Pew Research Center says that “34 percent of Americans reject evolution entirely.”

The initial conflicts about evolution that the plaque reminds us of were just at the beginning of a century of debate on the topic. The debate began in the state legislature, where Rep. George W. Ellis proposed the first bill to ban the teaching of evolution in any public institution. The “Monkey Bill,” as it was known, was defeated by a vote of 42 – 41.

Frank McVey, UK’s president at the time, spoke against the bill. William Jennings Bryan spoke in favor of it. At the time, Bryan was one of the most famous figures in America: He was a presidential nominee, Secretary of State under Wilson and a Congressional representative. Bryan traveled extensively throughout Kentucky speaking against Darwinian teachings in the early 1900s, as did religious leaders.

So Kentucky was the initial battleground for the debate over evolution, but its most famous fight was in Tennessee. In 1925, the state passed a law banning the teaching of evolution. The ACLU responded by offering to represent any teacher who broke that law. Businessmen in Dayton, Tennessee, arranged for the trial to happen there and John T. Scopes, a local teacher, became the scapegoat for the case.

“The Chamber of Commerce of Dayton did it as a kind of publicity stunt and let me tell you, it paid off big time,” Jones said.

The ensuing trial attracted national attention, with newspapers and radio giving daily updates. Bryan was the prosecuting attorney, using his gift of elocution to great effect. All of the attention caused the Monkey Trial, as it came to be known, to be remembered as the major culture clash and turning point of the evolution debate, even though it happened three years after Kentucky’s Monkey Bill.

UK is connected to the case in several ways. Scopes was a 1924 UK graduate and he was taught by UK professor Arthur Miller, an early adopter of Darwinism who served as a witness for the defense in the Scopes trial. Both are named on the plaque.

“I think we should be proud of the fact that (Kentucky’s anti-evolution bills) didn’t pass and that the man who allowed himself to be tried, a phony trial, was a graduate of the university,” Jones said.

Scopes was convicted and fined for teaching evolution. UK students, who had largely missed the public fervor that led up the Monkey Bill in Kentucky because of the first World War and its aftermath, took an interest in the fate of their classmate John Scopes, Jones said. Students even created a satirical float in the end-of-school parade depicting seniors evolving from freshmen.

“That’s what universities are about,” Jones said. “Intellectual discourse and the promotion of accurate beliefs.”

The idea that a small land grant university was an early adopter of Darwinian teachings and that its students and professors had a role in these pivotal events is special, and something Jones hopes the plaque helps people remember.

“I think we should have a memorial to people who are intellectual leaders on a university where that’s an important matter,” Jones said. “We have monuments to all sorts of things— why buildings were named, and that sort of stuff— this seems to be to be in the big picture, a good deal more important than who won the most ping-pong tournaments.”