Two among thousands: Meeting Sean Culley and Taylor Nolan

April 1, 2019

In January 2019, the unexpected deaths of two of UK’s own students left many on campus asking for answers.

In hopes of furthering an already growing dialogue about mental health and the resources available to UK’s students, the Kernel has spent the last two months learning about who Taylor Nolan and Sean Culley were during their time at UK.

Carefully and honestly, we set out to meet their friends, families and anyone who could help us tell each of their stories. We listened to what they had to say, sat in their homes and often asked questions that were tough to answer – never in an attempt to cause harm, but always in hopes of accurately and truthfully spurring a conversation about mental health.

In doing so, it was evident that Taylor and Sean each faced their own problems, but it was just as apparent that each of them were normal students.

They made friends, had their own talents, played sports, joined clubs, helped others, visited home for the holidays, had pets, did homework, walked to class in the cold, had jobs, and so much more, just like other students.

Each of them lived their lives and were loved by others along the way.

While we set out to learn as much as we could about Taylor and Sean, it’d be foolish to think that any of us could ever have all of the answers.

Dr. Julie Cerel is a licensed psychologist, a professor in the UK College of Social Work and serves as the president of the American Association of Suicidology. In an interview with the Kernel, she said that in cases of suicide, often no one has the full picture, but only small pieces to a larger puzzle.

“I think it’s hard for people left behind to understand why the person they cared about left them when perhaps so many people were pulling for them,” Cerel said. “A lot of the times the people left behind feel guilty, and say ‘Oh, only if I had done this or that.’ But no one has the full picture oftentimes.”

In a February interview with the Kernel, Cerel said her biggest advice to UK students was to look out for their friends and for the people they care about. Just talk to them.

If you are concerned for someone you know or are seeking further support, the UK Counseling Center offers walk-in crisis appointments for those seeking immediate assistance. You can also make non-emergency appointments throughout the week with UKCC’s trained clinicians. If you need to consult with someone from the UKCC after business hours, you can call 859-257-8701.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is available 24 hours a day at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

You can also contact the Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

The following stories attempt to paint a picture of who Taylor Nolan and Sean Culley were and what each of them means to the people who love them.

There are upwards of 30,000 students who enrolled in courses at UK. It’d be impossible to think that you could meet all of them, but here’s an easy way to meet two more.

—

Taylor Nolan

‘She did everything she could.’

Taylor Rae Nolan was ready to start the Spring semester.

She packed her things and made the nearly hour-and-a-half-long drive back from winter break at home in Springfield, Kentucky, to Lexington. She had just gotten her hair done, and had a few new pieces of clothes and a planner with every one of her upcoming exams penciled into it in her curvy handwriting. She seemed excited to get back to UK.

When she got back to the Chi Omega house where she lived on campus, Taylor went to see her therapist, something she had been doing every Monday for weeks.

Taylor’s closest family and friends knew she had been dealing with depression and anxiety for some time now. But to everyone around her, it seemed like she was taking all of the right steps to help herself.

She was on medication, had been actively seeking professional help and openly sought the support she needed from her friends and family.

The next day, one day before she was scheduled to start her fourth semester at UK, Taylor woke up and went to her job at iHeart Radio. She had made plans to meet a couple of her friends after her shift ended at 5 p.m.

But at close to 6 p.m., Taylor texted and said she needed to make stops at the grocery and the bank before coming over. She never made it to see her friends.

That night, Jan. 8, Taylor died of suicide. She was 19 years old.

‘She loved life, and it loved her right back.’

From the minute she learned her first word, Taylor never stopped talking.

“She spoke at nine months old and she never stopped,” said Taylora Schlosser, Taylor’s mother. “I was reading her a Veggie Tales book and it was about a ball and she said ‘ball,’ and there we went. I don’t think she ever stopped talking.”

Taylor grew up as the closest thing to a princess a little girl in Kentucky can be. The youngest child of her family and the only girl, Taylor was the baby of the family, and she expected to be treated as such.

“We did all the things little girls do. Makeup and hair and clothes… but she was the little girl that knew about Rambo and Rocky and all those kinds of things,” Mrs. Schlosser said. “She and I were outnumbered.”

But even if she was outnumbered, that didn’t stop Taylor from growing up strong and blazing her own trail.

Fast forward 18 years later, and that little girl with blonde, curly hair who never stopped talking graduated high school in the top 20 of her class and was set to bring all of her “spunk” and smiles to UK in the fall.

“We made multiple trips, and sometimes multiple trips to the same place,” Mrs. Schlosser said. “But she knew she wanted to be at an SEC school, and she said she ended up deciding she wanted to be at the University of Kentucky. I remember her being very emotional about that, because it was a really big decision for her.”

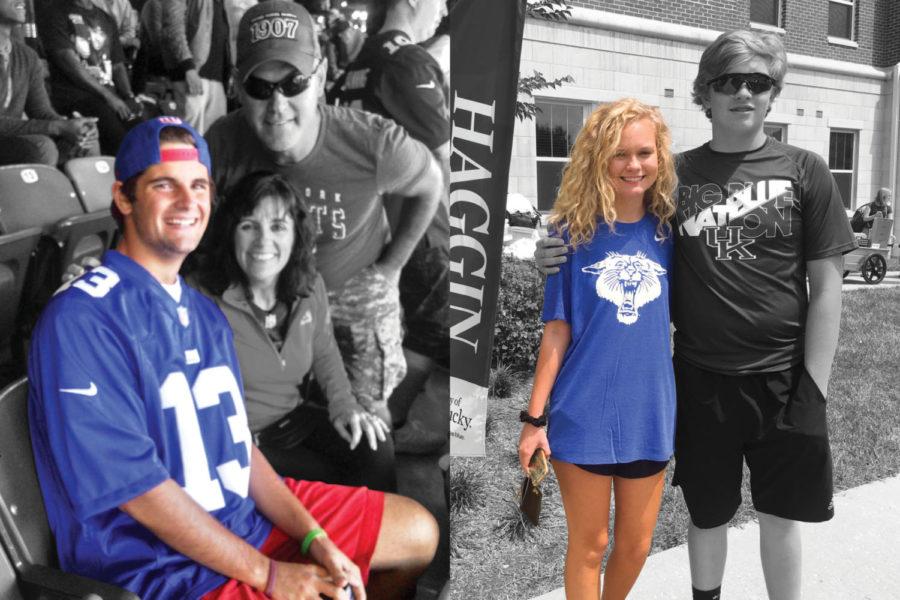

Taylor started her classes at UK in August 2017, and from the minute she stepped foot into Haggin Hall with her collection of UK t-shirts in tow, it was clear she was a hit with everyone she met. Most of them say it was her infectious smile and passionate personality that made her shine.

“Instantaneously, I knew she was just bubbly and cute, and I knew we were going to be friends,” said Lauren Mason, Taylor’s sorority sister and coworker. “What struck me the most about her is that everything she’s involved in, she’s like the most passionate person in the world about it. She could talk to you about what shampoo she uses for 45 minutes because it was just the best thing in the world to her.”

Some were even finding excuses to talk to her.

“I ended up looking over at her computer and seeing she was doing chemistry homework, and I was doing chemistry homework. I knew what I was doing, but I said, ‘Hey do you want to help me?’ I made myself look stupid so I could ask her for help,” said Taylor’s eventual boyfriend Noah Anthony. “She just drew people in… I was making up reasons to talk to her. She was so smart, intelligent and beautiful. She just had a lot of things that people wanted to be around her for.”

Taylor quickly found her homes on campus and started making friends. She joined the Chi Omega sorority and was elected as a freshman senator to the Student Government Senate.

For those watching Taylor, it was obvious she wanted to use that same passion of hers to make an impact on others.

“It was not a one-way street with Taylor. From the moment you met her, it didn’t matter who you were or where you came from,” said Courtney Wheeler, Taylor’s friend and SGA Senate president. “She loved helping others. She loved supporting each other and all of our differences.”

Taylor excelled in the SGA and in Chi Omega. She was appointed as the Chair of the SGA Senate Operations and Evaluations Committee during her second semester and was eventually elected as an SGA Senator-at-Large.

Her friends in Chi Omega saw Taylor’s same determination and drive come alive in their own chapter.

“She was very determined, probably the most determined person I knew,” said Taylor’s sorority sister and eventual roommate Faith Turner. “If she wanted to do something, she was going to do it, and if she wanted you to do something, you were going to do it.”

Taylor was even voted “Most Likely to Become President” by her Chi Omega sisters. From the outside looking in, it seemed like Taylor’s life was perfect.

“She loved life, and it loved her right back,” Turner said.

‘Taylor Rae’s Support Group’

A year before her death, in late January 2018, Taylor was diagnosed with meningitis, an often life-threatening infection that attacks the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

She spent multiple weeks of her second semester at the UK hospital and at home in Springfield, instead of on campus. At times her friends and family feared for the worst, but Taylor fought and recovered with the help of her support system.

“If you hear that word [meningitis], typically that doesn’t end well,” Mrs. Schlosser said. “But she came home and I served as her hospice nurse, I guess you could say. You try to have a lot of talents and a lot of things on your resume, so I added that to my resume.”

Before she got sick, Taylor’s family had a group text message they called “Freaking Weirdo Family,”— “because we had a lot of fun, and we enjoyed each other,” Mrs. Schlosser explained.

As Taylor fought to recover, that group text name changed to “Taylor Rae’s Support Group.”

“As our family changed, our group text message changed as well,” Mrs. Schlosser said.

With mountains of flowers and encouraging text messages pouring in, Taylor had a lot of people in her corner, which only increased her desire to get back to campus.

“There was no question. She was going back. She wasn’t staying home. She wasn’t dropping out. She was going back to the UK that she loved,” Mrs. Schlosser said.

And once Taylor got back to UK, all of that support she received didn’t stop flowing in. Her closest friends knew she was sometimes dealing with bouts of anxiety and depression, and they made sure to be there for her when she needed them.

Taylor’s closest confidants say she had a tough semester to balance in the fall of 2018, even for someone who seemed to have super powers like she did.

“I just think she didn’t give up. So even if she did feel like she was overwhelmed, she wasn’t going to be the person to say ‘I can’t do it,’” said Taylor’s friend and sorority sister Casey Sartore.

Taylor was living in the Chi Omega house, had previously accepted an internship at Lexington’s iHeart Radio, was still involved with the SGA and had even picked up another major. She was studying Integrated Strategic Communications and Digital Media and Design.

“She was really busy. I felt like she was probably super busy over this fall semester,” Mrs. Schlosser said.

Taylor eventually resigned her position in the SGA in September 2018.

“She really loved SGA. I know it probably broke her heart to have to leave it,” Mason said. “I think she just felt like she was spread too thin.”

To her friends and family, it looked like Taylor was taking the right steps to avoid being overwhelmed. They say they saw that because Taylor was always very open with all of them.

“When she was upset, she was going to tell you. You knew when she was upset, she was texting saying, ‘I need to talk. I’m upset. This happened.’ She never hid her feelings really,” Sartore said.

Taylor was like an open book.

“Most people when this happens, you don’t know what’s going on in their life, but with Taylor you knew everything,” Mason said. “She met you, and she unloaded.”

They knew how Taylor felt. They saw she was taking care of herself.

Taylor tried to go to therapy every week and had been prescribed medication to help with her mental health. Taylor’s friends say she recommended therapy to everyone she met.

“She was actually so knowledgeable about mental health,” Turner said. “She was very into therapy. She was very into it. She loved it. She had a therapist that helped her a lot.”

But aside from the professional help she was getting, and the support she received from her friends, Taylor always knew she could talk to her family.

“If she was worried about something or she was feeling anxious about something, I mean we talked. She told me. We talked it out… so I felt like she could call me… because she did. She called me about happy things, or if she was worried about something,” Mrs. Schlosser said.

Mrs. Schlosser said Taylor would come home for a good meal and a rest.

“Sometimes she’d just come home to take a nap, and she’d tell me what’s going on and we’d talk about it…” she said. “We would have those conversations.”

Taylor and her mother often talked about achieving a balanced life, so when it came time for Taylor to go back to UK in January 2019, Mrs. Schlosser thought she was ready to go.

“If you looked at anything Taylor had on her bulletin board, anything she wrote down, anything she painted, you knew she knew how important that balance was and how important that growth was…” Mrs. Schlosser said. “I was under the impression we were ready to go back to school, and she was fired up and ready.”

But no one in Taylor’s life was aware she contemplated suicide.

A ‘Rae of Sunshine’

Taylora Schlosser typically wears pearls, but now that her daughter is gone, her wrist is filled with bracelets and tokens that used to belong to Taylor.

If you walk into the front door of Mrs. Schlosser’s home in Springfield, it’s hard to find a wall without a picture of Taylor grinning ear-to-ear with her signature smile on it. The entire house is dotted with memories of Taylor and gifts she gave to her family.

“Taylor was the kind of little girl that was very giving. Not just all kind and sweet and smiles, but she always gave me gifts,” Mrs. Schlosser said.

Taylor loved art, and she was talented. When her family members’ birthdays rolled around, she often gave her artwork as gifts.

The mantle at Mrs. Schlosser’s home is adorned with a record her daughter painted for her during her last semester at UK. It sits right next to a flower display that was on Taylor’s casket at her funeral. The scene painted on the record combines their mutual love of music and Mrs. Schlosser’s love for the state of Colorado.

For weeks after Taylor died, Mrs. Schlosser would leave some of the paintings her daughter painted sprawled across her own bed. Every morning, she would make her bed and then display the paintings— for herself and for any visitors who were coming by the house.

“Every morning that’s what I would do. I would get up and make my bed and lay out her artwork. So, it was helpful. It was helpful,” Mrs. Schlosser said.

Venture downstairs to Mrs. Schlosser’s basement and you’ll find a room that houses boxes of old paintings and drawings from when Taylor and her brothers were kids. A few feet above those boxes hangs a wall that draws comparison to a florist’s shop. Mrs. Schlosser has hung bouquets from Taylor’s funeral there as a way to remember her daughter.

All of the mementos that fill every inch of Mrs. Schlosser’s home serve as constant reminders of who her daughter is.

“In my home there are so many things Taylor has given me. So after her passing I didn’t have to rearrange my home to add things, because everywhere I look there is something she has given me,” Mrs. Schlosser said.

But Mrs. Schlosser said that even without these special gifts, it’s easy to remember Taylor’s spirit. And she wants to share that smiling and bubbly spirit with others.

That’s why Mrs. Schlosser has started the Rae of Sunshine Foundation. For the foreseeable future, she plans to travel the state and speak at different schools and universities, sharing Taylor’s story and advocating for awareness about mental health along the way.

She says that’s what Taylor would want her to do.

“Taylor would want us to tell her story,” Mrs. Schlosser said. “She would want us to find a way to keep that present at the University of Kentucky, in my home, in your home, at other colleges and universities for other children her age. That’s what she would want. It is a tragedy and it’s unfortunate. My family and I, we are heartbroken. We are devastated, but we have to find a way to spread more sunshine.

“The one thing I told some folks is that I don’t want this to be a story book. I want Taylor’s life to be a chapter book, and Jan. 8 was just one part of a chapter. We can still write chapters of Taylor’s life for many, many years to come.”

Taylor will turn 20 years old on April 28. Every year on her birthday, Taylor and her mother would spend the day together shopping. That trip was “always more about the experience than the gift,” according to Mrs. Schlosser.

So this year when April 28 rolls around, Mrs. Schlosser said that Taylor’s roommates have offered to fill in.

“For me and for missing Taylor, her friends have been a real joy,” Mrs. Schlosser said. “I do feel like they’re all a part of this.”

For Mrs. Schlosser and the rest of those who knew Taylor, they will forever remember her as a “Rae of Sunshine,” complete with her signature curls and that big smile.

“It’s been pretty cloudy lately, but when the sun shines we appreciate it, and I think that’s what our foundation wants to do,” said Mrs. Schlosser said. “…We just need to smile more. We all need to smile more.”

—

Sean Culley

Winters in Brick, New Jersey, can get cold.

Cold enough that during this January, when Sean Culley’s family ran out of room in their refrigerator, they were able to stack the piles of food they were getting from their neighbors outside.

“As we came back into our house, we had neighbors bringing food over… the refrigerator was stocked for the next three or four days,” said Stephen Culley, Sean’s father. “It was at least cold enough to stack some food outside, because they’d come in the front door and I’d stack it outside in the cold. We started using neighbors’ houses to hold all the food, because people didn’t know what to do, so they’d send food.”

Sean had been struggling with depression since his junior year of high school, but he decided to keep that part of himself a secret when he started classes at UK as a freshman in August 2018.

A semester later, on Jan. 23, Sean woke up in his dorm room in Woodland Glenn III at close to noon, then showered and asked his roommate Joe if he wanted to eat lunch. But Joe had just eaten, so Sean left the dorm alone and went on his way.

Sean died of suicide later that afternoon.

There was no way for Joe to know what Sean was about to do because he never told any of his friends at UK about his ongoing struggle with depression. In the words of Sean’s father, he simply put on his mask.

“He had a mask he would put on basically, and you wouldn’t be able to tell. He was a big schmoozer. He should’ve been a politician,” Mr. Culley said.

‘The happiest one in the room’

In the neighborhoods of Brick, New Jersey, the houses are close together.

It’s the type of place where kids and their friends play on the same sports teams, and those teammates’ parents become friends themselves.

Sean grew up playing basketball, soccer, lacrosse and anything else he could get his hands on. So from the start, he had lots of friends.

“There was always some other kid in the house, or he was at their house. So it was pretty active that way,” Mr. Culley said.

From the minute Sean was born, it was clear his life would be tied to sports. The night he was born, Sean’s father was rushing from New York City back to New Jersey.

“I was able to able to make it from New York City to Brick in one inning as the Yankees sealed getting into the World Series,” Mr. Culley said. “And then rolled into a Monday night football game, so it was a good night the day he was born.”

Sean was the youngest of three children and one of many cousins in a big New Jersey family. But he never let his age or size stop him from being part of the action.

“Sean was forever trying to catch up with them to be able to play ball, or play Nintendo or play whatever games were going on,” Mr. Culley said. “He was always stretching to play higher with kids who were older than him.”

But when Sean got older, he “remembered being the little guy” so he made sure he stayed out and played with the younger ones, Mr. Culley said.

It was easy to see that Sean was competitive and driven, but kind and compassionate at the same time, according to his father. And he carried those same qualities with him when he came to UK in the fall of 2018.

Sean was studying pre-materials engineering at UK. His goal was to graduate and work on designing and making prosthetics.

The first week he moved into his dorm, Sean didn’t wait very long to start making friends.

“He and a group of guys knocked on the door, and I answered it and he said, ‘You must be Joe, right?’ and I said ‘Yeah,’ and there were about five of them and they said, ‘We’re going to be your friends now,’” said Sean’s eventual roommate Joe Schuler. “It was Sean who decided to come and knock on the door. He didn’t know many people coming here, so he wanted to get right into it and skip all the formalities and everything and just jump into ‘We’re going to be good friends.’”

Sean’s friends say that he was usually the “catalyst” of getting everyone together. He was always the happiest one in the room.

“I never even saw him as anything other than happy,” Schuler said.

When all of Sean’s friends returned to campus from winter break, none of them were aware that Sean was in a year-long battle with his own mental health and had been seeking professional help.

‘His demons’

When he gave his son’s eulogy, Mr. Culley wrote that Sean’s life “wasn’t all sunshine and roses.”

“Sean struggled with depression and that was part of him too. I remember the first time I saw that demon,” Mr. Culley said.

Mr. Culley first saw glimpses of his son’s depression during his junior year of high school. Sean was playing in a varsity basketball game – a game his team wasn’t supposed to win. Sean got subbed in and immediately started hitting three-pointers. It looked like his team might actually win, Mr. Culley said.

But when the fourth quarter started and it was clear the game was on the line, he looked over and Sean wasn’t on the court. He wasn’t on the bench.

Sean couldn’t manage to get himself back out on the court. It was his depression that was holding him back.

“I went down to find him as he walked out of the locker room and there was something missing in his eyes. He was trying to get himself back. They lost that game. That was my son,” Mr. Culley wrote in Sean’s eulogy.

After that game, Sean and his family started seeking professional help. Sean was prescribed a variety of medications to help with his depression during his senior year of high school, and he started seeing a therapist.

It seemed like Sean was getting better. He went off to start college at UK, and was off of his medication for the entire fall semester. He was happy.

But when November came around, there seemed to be a lot more phone calls coming in from Sean, Mr. Culley said.

“We pretty much talked every weekend, and then during November there seemed to be a lot more phone calls coming through. Probably three times a week,” he said.

When Sean came home for Christmas break, it was clear to his parents that he was struggling again. Sean told them he needed some extra help, so he made a plan to visit the UK Counseling Center when he got back to campus, Mr. Culley said.

Sean wanted to get more help. But looking back, Mr. Culley said that Sean had likely already been planning his suicide.

“I think at that point he had been planning it in his head,” said Mr. Culley.

‘He had me fooled’

Mr. Culley spoke to Sean on the night of Jan. 22.

Sean was out to dinner with his roommate Joe and some of Joe’s family friends. They were planning to go to a UK basketball game afterward.

“I interrupted the dinner so he came out to talk to me for a few minutes to let me know they were taking him out. So I told him to get back inside,” Mr. Culley said. “He sounded rather excited. I hung up the phone thinking he was doing great. He had me fooled.

“Somewhere along the line, he had it in his head he was going to do it, but I don’t know what triggered him that day, that that was the time. But I’m pretty sure a few hours before, he did not know.”

Now that Sean is gone, his family says they are left with a lot of questions.

“Well, we spent the first few days crying our eyes out,” Mr. Culley said.

Things around the family’s home reminded Mr. Culley of his son in the days following his death.

“I think it was two days before I put down his basketball,” Mr. Culley.

Mr. Culley said the family was in shock at first.

“Going through a little different times of everybody falling apart, and we had to get to a point where we went back to school and went back to work,” he said.

The one thing the Culleys are sure of is that Sean was loved.

“It was not a matter of not being loved. He knew he was loved. He felt the love,” Mr. Culley said.