Men outnumber women among UK faculty, especially in STEM fields

November 2, 2020

Academia has a diversity problem; in recent years, universities across the country have begun diversity initiatives that focus on recruiting faculty to more accurately represent the student population. One of the key benchmarks in this nationwide conversation is the unequal proportion of male and female faculty; UK is not exempt from this conversation.

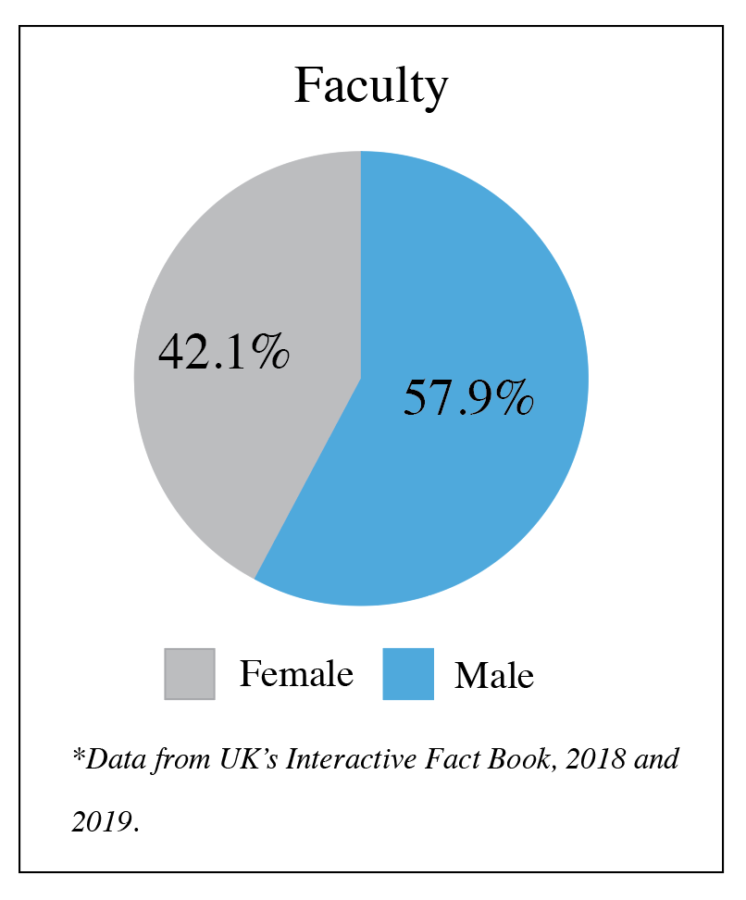

According to UK’s Interactive Fact Book, in 2018 and 2019 57.9 percent of all UK faculty members were male and 42.1 percent were female. Meanwhile, the student population was majority (55.2 percent) female in the fall of 2018.

UK’s gender discrepancy between faculty and student populations is in line with nationwide trends; gender representation among faculty has become a serious research topic in recent years. At UK, the mismatch in gender demographics is present across rank and position of faculty members.

For the 2018 – 2019 academic year, UK’s Interactive Fact Book listed 747 faculty members that were categorized as full professors, 553 (74 percent) of which were listed as male and 194 (26 percent) listed as female.

According to the National Center for Educational Statistics, around 73 percent of faculty members ranked as professors nationwide are male, consistent with the numbers seen here at UK.

In addition, STEM fields are known for having noticeable gender gaps from as early on as elementary school and continuing into the workforce demographics of today, including in higher education.

According to a 2019 report by the National Science Foundation, in 2017 women made up 38 percent of science and engineering doctorates employed in higher education across the country, which is up 13 percent from 1997. The NSF report also found that women accounted for 32 percent of full-time senior faculty (including full professors and associate professors) in 2017, which had nearly doubled from 1997.

The proportion of male to female faculty varies widely depending on the discipline. Nursing is a female-dominated STEM field, whereas physics is largely male-dominated. While these numbers do show the growth of the female workforce in STEM, it still leaves women in the minority in the field as a whole.

UK’s Interactive Fact Book only lists faculty selections by college, so it cannot be used as a measurement tool because STEM programs are spread across nearly every college on UK’s campus. However, Some STEM department chairs were able to provide department specific numbers to the Kernel.

Al Shapere, chair of the UK physics and astronomy department, said with physics being one of most male-dominated fields worldwide, he has seen this discrepancy first hand and even in his own department where only three out of 31 employees are female.

Shapere said his department and the entire College of Arts and Sciences is working to increase their number of female employees.

“The College of Arts and Sciences has 106 Assistant Professors, of whom 62 are female, or about 58 percent. These are all faculty hired within the last six years,” Shapere said. “This number shows the College’s strong commitment to increasing the number of women faculty.”

As for the discrepancy in faculty ranking, Shapere said, “These things can’t be changed overnight, but eventually most of these assistant professors will become full professors, and if hiring continues at its current rate, we should be at 50 percent within seven years or so.”

The Department of Biology, also housed in the College of Arts and Sciences, paints a different picture of a male to female faculty ratio in STEM.

Vincent Cassone, chair of the UK biology department, said the department currently employs 15 female faculty members and 22 male faculty members; however, he said the department will continue recruiting not only female faculty but also continue increasing their overall faculty numbers to fit the growing number of biology majors at UK.

“These are hard times for higher education, and biology has too few faculty for the numbers of biology and neuroscience majors here,” Cassone said.”We desperately need to grow at a time when resources are scarce.”

Faculty members and students at UK and across the country have taken note of gender discrepancies and the issues they cause, and some are now focusing the conversation on solutions.

One of the main concerns in this mismatch between student and faculty demographics is the effects it can have on student success.

“When students have fewer role models and mentors who are women full professors this can certainly also impact how students understand possibilities and obstacles for women in higher ed, and for themselves,” said Cristina Alcalde, associate dean of inclusion and internationalization in the College of Arts and Sciences and Marie Rich Endowed Professor of gender and women’s Studies. “The picture is starker for BIPOC populations, who are less likely to find Black, Latinx, Asian, and Native American women in senior leadership positions.”

Susan Gardner, a professor in the UK physics department, said she has seen this same issue in her classes. However, she saw the opposite effect for those students who were taught by faculty that they identified with.

“I do have the impression from interacting with my students and chatting with my faculty colleagues that female students may feel particularly encouraged to succeed when they are taught by female faculty,” Gardner said.

Katherine Paullin, faculty lecturer in the UK mathematics department, said she has similar concerns for the STEM field, saying that this representation matters especially in the fields where women are often underrepresented in hopes that it will draw more females to be comfortable in the field.

“Students need to see faculty that look like them in order to believe that they can achieve success in that field. This applies not just to gender, but also to race and class, and starts long before students come to college. Having more women in STEM faculty,

increases our chances of having more female STEM majors,” Paullin said.

Darcy Adreon, a sophomore biochemistry and spanish dual degree, said she hadn’t noticed a gender discrepancy in her classes until she reached her higher level courses, where she noticed most of the professors are male and there are fewer female students.

“Girls will always be drawn to science in the same way young male scientists are fascinated by it. The real issue is paving the way for women to stay interested and showing them that they are equally capable of becoming involved in science,” Adreon said.

Adreon and Paullin both said solutions to this issue, beyond UK, begin with changing how the public perceives STEM and the stereotypes surrounding it.

Matthew Farmer, a senior biochemistry major, said students and faculty can both be a part of the solution.

“Our chemistry department’s diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) committee and our very own ChemCats organization has thought and discussed this issue from varying angles. What became apparent immediately from these discussions is that this isn’t a one-dimensional issue,” Farmer said. “This will take a monumental effort with presentation (faculty and student) from every college in the university to limit blind spots of inequality. Everyone at the University of Kentucky deserves equity. We’re fighting for it.”

Aside from departments and students, colleges and the university as a whole are also taking steps to work toward a more diverse faculty not only in STEM but universitywide.

Alcalde manages several initiatives within the college to better diversify faculty not just by gender but also other forms of diversity.

Alcalde said while the college itself has a DEI plan, each department is developing its own version to discuss a path to a more diverse faculty at that level.

Alcalde said the College of Arts and Sciences also created a College Diversity and Inclusivity Committee, including 10 faculty, staff, and student representatives from the natural sciences, humanities, and social sciences to discuss topics related to diversity and inclusion regularly.

They are only developing DEI modules for international students, which include materials on trans allyship, gender pronouns, and LGBTQ histories, linguistic diversity, and several other topics.

The college also has the Faculty inclusion Fellows Program to support faculty-proposed initiatives to increase diversity and inclusion efforts to benefit students.

“We have funded several STEM faculty-led initiatives through this, including initiatives to bring in more women speakers in math and statistics and efforts to further diversify biology peer instructors,” Alcalde said.

The university as a whole is also making efforts to continually increase diversity and educate others on the subject through numerous initiatives such as the new online graduate certificate in diversity and inclusion.

Kathryn Cardarelli, senior Assistant Provost for Faculty Affairs and Professional Development and an Associate Professor of Health, Behavior & Society at UK, said she and her department work directly to increase diversity by gender, race, ethnicity, and a wide range of other forms of diversity

Cardarelli said her department keeps workbooks to track the progression of diversity at the school, especially in terms of tracking how many female employees are moving into tenure eligible positions like professor and increasing diversity in leadership.

Cardarelli also said her office is currently working to expand section on diversity recruitment in their Faculty Hiring Toolkit, a guide for colleges and departments to use in the hiring process,

Cardarelli also said that there were offices and people all across UK that were committed to this same initiative, including the Vice President for Research and the Dean of the College of Engineering.

“We want all of our students to be able to look across the faculty ranks in their college and see someone who looks like them and or who has had experiences like them,” Cardarelli said. “We want to cultivate a community belonging for everyone.”

While Cardarelli said her office is hard at work toward the goal of diversity, she does understand that UK’s commitment to bridge the gap between faculty and student demographics is far from over.

“If everyone looks one way and then students look another way that that’s not going to work. I do think that we’re getting better,” Cardarelli said. “I do think we have a long way to go.”

A previous version of this article misspelled Kathryn Cardarelli’s first name.