Kentucky Kernel marks 50 years of editorial independence

September 11, 2021

In the spring of 1971, there was one thought on the mind of the University of Kentucky’s trustees: ‘how do we get the Kernel off our hands?’

The Board of Trustees’ answer to that question led to the Kentucky Kernel becoming the paper it is today, a financially and editorially independent student newspaper that serves as a bastion of free speech and free press. 2021 marks 50 years since the Kernel became independent and Kernelites both past and present are proud of that legacy.

But how that independence came to be is a lesser known story, one that Kernel archives show to be a concerted effort by members of the university’s Board of Trustees to eradicate the Kernel due to their outspoken editorials.

“The tension sort of began about a decade earlier when the Kernel began to editorialize in favor of allowing for integration of the SEC,” said Duane Bonifer, who was on the Kernel staff from 1986 – 1991 and now serves as chair of the Kernel’s Board of Directors.

The Kernel was one of the early leaders in the South calling for integration, Bonifer said, which the university’s “pretty conservative” board objected to. A previous Kernel editor resigned without publishing an issue in protest of the university assigning the Kernel an advisor in an attempt to control the paper’s coverage – including barring content about integration from the paper.

Combined with growing political activism and youth empowerment movements of the 1960s, the Kernel transitioned into a serious student newsroom that pursued journalistic integrity at a higher level than ever before – and that was a threat to a university campus.

“The Kernel staff has worked under the concept of a free student press, rather than being parentally restricted to the whims of a University administration or a Board of Trustees,” said a column about the power of student press in the Kernel’s April 7, 1971 edition, published the day after the fateful board vote that cut off the Kernel’s funding.

The initial article on the decision was by Jean Renaker, the managing editor at the time, and also appeared in the April 7, 1971 edition of the Kernel. Renaker said that university president Otis Singletary proposed the Kernel’s budget be cut in half, which was accepted by the Board of Trustees with an amendment that the reduction take place within one calendar year.

An editorial from then editor-in-chief Frank Coots, entitled ‘Kernel victimized by politics,’ decried the decision as a failure of the Board of Trustees to fully consider the thoughts of students and faculty in the decision.

Still, Coots noted that the compromise – letting the university’s funding fade out in the next year – was better than the original plan favored by at least three board members, which was to cease funding immediately.

“This, of course, would have killed the Kernel,” Coots wrote. He noted that the financial change was actually to the benefit of the Kernel, which would now be printed off campus and cut publishing costs in half.

“They looked all over the state to find a printer who would agree to print the Kentucky Kernel, really on faith more than credit, because the Kernel had no credit,” Bonifer said.

In his piece, Coots affirmed the Kernel’s commitment to keeping papers free of charge and laid out the plan for the newsroom’s continued operation.

“When the paper became independent, we basically had to start over,” said Michael Wines, a Kernel staffer who took over as editor-in-chief after Coots.

Still, the decision – veiled as an objection to using taxpayer money for a student paper – came across as reactionary to the Kernel’s history of, to speak euphemistically, persistent journalists, and the educational value of a student press was “always second on the list when compared to the university’s fear of a dissenting campus newspaper,” according to the editorial ‘Trustees can cut off Kernel funds, but not student power.’

Kernel staffers from 1971 and 1972 characterized the move as lashing out at a student press that was not afraid to criticize either the state or university administration. So long as they kept quiet, they believed they would have been allowed to continue as they were. But staying quiet wasn’t in their nature or their mission.

“As state officials came under attack, they responded with criticisms of their own,” Coots wrote about the Kernel’s pointed editorials. But those officials also had the power to silence the Kernel by influencing the Board of Trustees, and notable politicians sat on the board themselves.

The governor at the time, Louie Nunn, sent a state trooper to Lexington to pick up the Kernel and former Kentucky governor Happy Chandler vowed to “abolish that stinking sheet.” Nunn controlled UK’s board by appointing his own men, which allowed the funding ceasure to pass after failed attempts in earlier years.

One of the board members who voted for immediately cutting off the Kernel was the owner of another paper, the Wildcat. Even the efforts of UK president Otis Singletary were not enough to sway the board. Singletary, who had a known fondness for student papers, was cited by Coots as the only reason the Kernel was not cut off entirely and immediately.

“Singletary, at least, I won’t say give it a lifeline, but he didn’t pull the plug,” Bonifer said. Others were not as inclined toward benevolence for the Kernel.

“This is only manslaughter. I wanted murder,” Chandler is reported to have said of the tempered decision. Chandler, who would be appointed to the board again in the 1980s, continued his dispute with the Kernel for the rest of his life, including an altercation where he punched a student reporter – an act for which he received a letter of commendation from J. Edgar Hoover, then-director of the FBI.

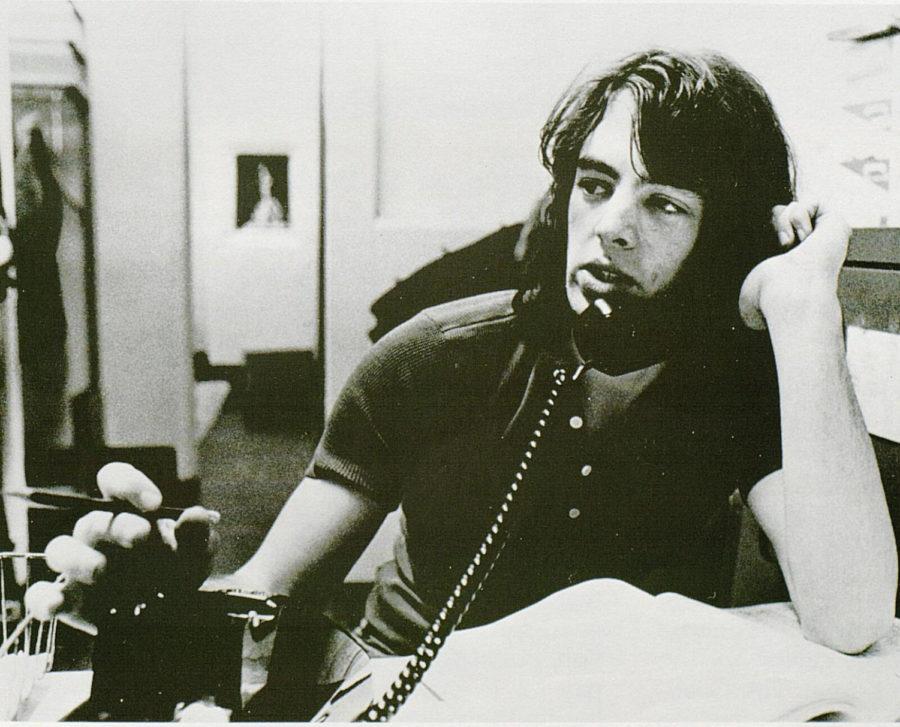

Wines testified to the frictious relationship between the paper and university officials. When the Kernel caught wind of unethical aid being given to members of the basketball team, Wines himself was threatened by an administrator.

“I got a call from the sports athletic guy telling me that if we ran the story, I’d never find a job in Kentucky again,” Wines said. “So we had our share of run-ins with authorities.”

Wines, now a correspondent for the New York Times, went on to get a Master’s in journalism from Columbia University. Many of his peers from the Kernel had equally successful careers, including former White House correspondent Bill Straub.

But in 1971, Kernel editors were aware that they were lucky to survive, and though criticized for accepting the board’s decision without much pushback, knew they had little room to negotiate less they “face a sure death.”

“Talk about a leap of faith, man. The company that agreed to print the Kernel and said ‘yeah, we’ll believe that you guys are gonna pay us for doing this for you’ -” that printer, along with the editor who took over in the first year of independence, are the real heroes,” Bonifer said. That would be Wines and his crew of journalists, who embodied the scrappy underdog mentality Kernel staffers have become known for.

So the Kernel persisted, and in 1972 was publishing daily, independent papers with more pages than previous years – now tagged with the all-important “independent student newspaper” header at the top.

“We never really worried about being cut off,” Wines said. “And when it happened, I think there was a resolve among everybody just to go forward and be a better paper.”

As the first editor of the newly independent Kernel, Wines helped shape the Kernel’s commitment to solid journalism. He recounted that his focus was on “a nonpartisan enterprise, aimed at getting stories.”

“We definitely saw ourselves as a collegiate version of the fourth estate. And we felt that was very important to the students, first of all, which we felt was our first audience but also the families that read the newspaper,” Bonifer said.

This was especially important given the state of upheaval in the United States. Kernel reporters were swamped by the Vietnam War, integration, and a bevy of other social movements leading to riots and protests.

“Everybody was dedicated to being as good a journalist as we could,” Wines said. And for a lot of us, it really became a 24-hour job. I know I missed a lot of classes putting out the paper.”

Skipping class for the sake of the paper has become a rite of passage for Kernelites. But an even greater tradition from the 1970s has carried on to today – the same sense of free thought, speech and press that led to the Kernel’s independence.

“The Kernel’s very independent spirit and attitude of being a watchdog of the university as opposed to a lap dog or a cheerleader for the university was continued on…there’s always, always been sort of a sense of suspicion or tension since then between the university and the Kernel,” Bonifer said.

Through 50 years of independence, the Kernel has weathered many changes, going from a daily paper with 154 issues a year to a weekly paper. A transition to mostly online content has dropped the paper’s circulation, once one of the largest in Kentucky, from 17,000 to 5,000. In 2018 the Kernel moved out of its long-time home in Grehan, parting ways with the legacy remembered by generations of Kernelites. But the fundamental identity of the paper remains.

“The Board of Trustees cannot halt the thinking and power of a student community,” said the ‘student power’ editorial in 1971. “The Kernel will be just one example of how the student community can succeed.”

50 years removed from a tenuous start to independence, the Kernel has succeeded in that mission. Here’s to 50 more.