Hostile Terrain 94 conveys the deaths of migrants crossing into the United States through the poor terrains of the Sonoran Desert and are represented through toe tags with documentation in an exhibit.

The exhibit took place on Thursday Feb. 13 for students, faculty members and members of the community to visualize the dangers of the migrant trail in the Lewis Honors College.

Hostile Terrain 94 was created by Jason De León who has a doctorate in anthropology and is a member of the Undocumented Migration Project (UMP). This project promotes migration to “raise awareness” and encourage “positive social change,” according to the UMP website.

The art was designed to represent the migrants who died trying to cross the “hostile terrain” of the Sonoran Desert due to the “Prevention Through Deterrence” strategy created by the U.S. Border Patrol, according to UMP’s Hostile Terrain 94 website.

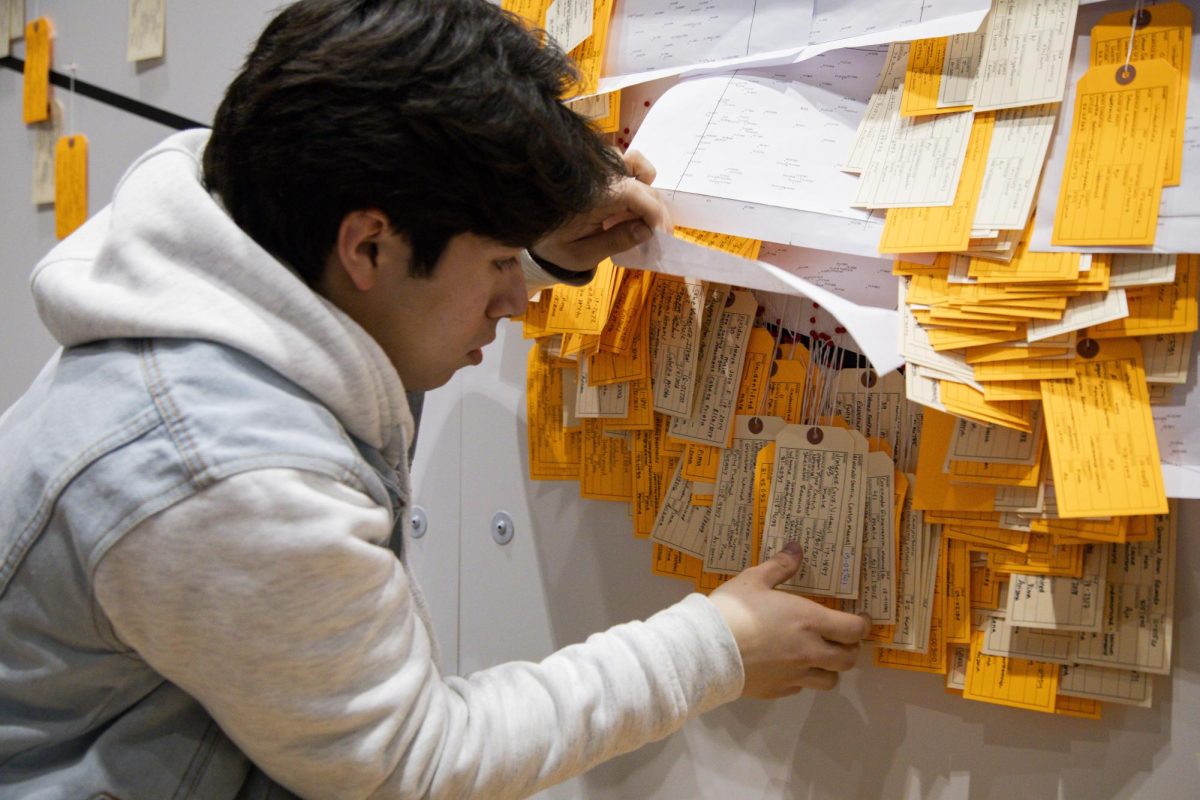

The art behind the exhibit is a map of the Sonoran Desert with tan and orange identification toe tags representing the lives lost on the trail and those whose bodies could not be identified.

“This exhibit is trying to let us memorialize the almost 5,000 people that we have recovered, that have died on the migrant trail and, basically, cultivate a sense of justice for everyone who has crossed and attempted to cross,” Zada Komara, a professor at the Lewis Honors College, said.

Komara also said that she hopes people feel this art on a “personal and emotional level.”

“It is a beautiful experiential education opportunity for Lewis students and the community,” Komara said. “I think it’s just an awesome way to practice social justice in a mixed media way.”

Students and professors were seen writing names on tags, how they died, their age and any other information known. Others helped by pinning the tags they wrote on the board and Heather Worne, an associate professor of anthropology, was one of those people.

“We know how long they have been out there. Some of them were five and some died more recently and they become real when you read their toe text,” Worne said. “I’m a bio-archeologist. I study human remains and it still affects me even though I’m used to working in that context.”

Former Lewis Honors College student Audrey Matthews-Fields said they felt compelled to come back to campus and help with the exhibit. They said that they used this opportunity to take things they learned in the classroom and apply them to real life.

“We had a lot of conversations about theory versus practices and how we take what we talk about in the classroom into our communities and into the spaces where they can make a difference,” Matthews-Fields said.

According to Matthews-Fields, the exhibit is “overwhelming” and a representation of the lives that were lost.

Ali Vargas, a civil engineering senior, said she had seen her parent’s luck when migrating to the U.S. and how hard it was for them to find work and get their citizenship. Vargas said some people “aren’t as fortunate” as her parents to make it safely to start a new life.

“It’s not just statistics that we’re looking at or just numbers on a paper,” Vargas said. “We’re able to see the lives affected by policies and different things that the United States has done.”

Professor of anthropology, Chris Pool, said that he has followed León’s work and finds the exhibit a great way to “express and to document that for a broader public that may not be aware.”

“We need to not just see pieces of paper hanging by string,” Pool said. “You need to see the people that it represents and the tragedy that it represents.”