At school and at home, father and son are together

March 4, 2014

By Rachel Aretakis | Editor-in-chief

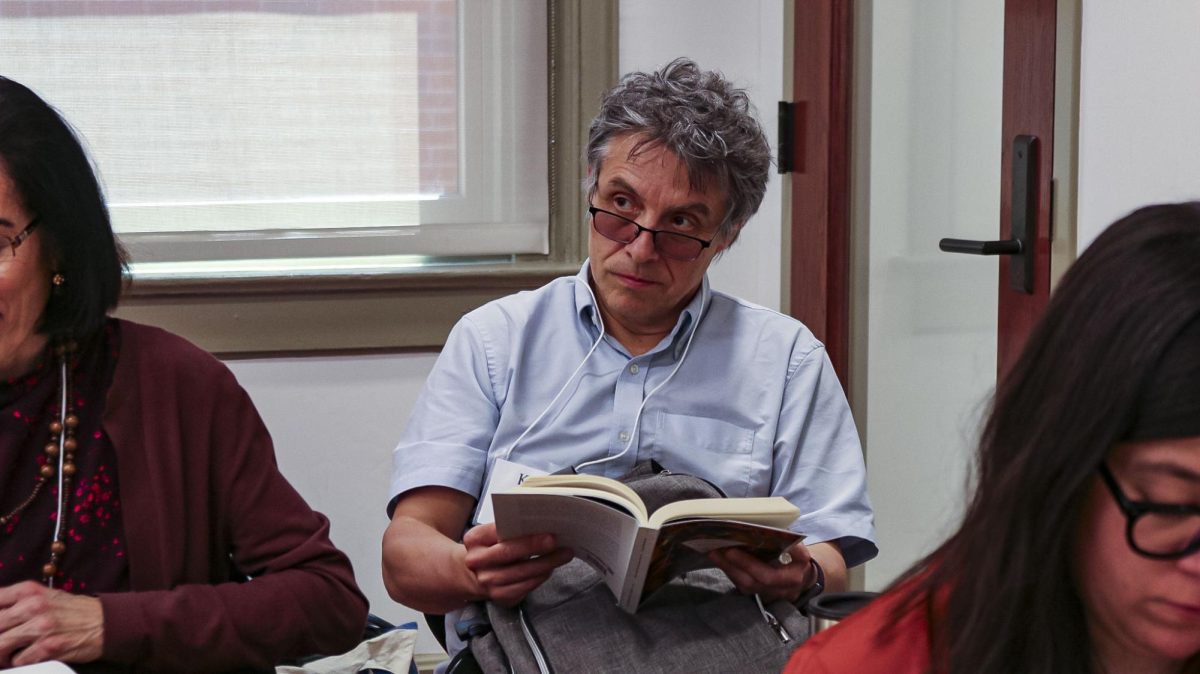

With his hat brim down and earphones in, Brad Pike guides his son through the cluster of students rushing out of class. He is unfazed by the chaos, looking ahead as he swiftly pushes the wheelchair through the door.

Pike is in his routine. He picks up his son, Haden, in the morning for class and later takes him home. While he’s waiting, he listens to the radio in his truck or goes to Haden’s apartment and makes lunch or cleans.

That’s his job most days.

“It is just normal for us,” Pike, 51, said.

Three years ago, Pike retired early because he knew he wouldn’t trust anyone else to take care of his son.

“I mean when it’s your kid,” he said, “you can do it better than anybody else can.”

Haden Pike, 20, has been blind since birth and has a degenerative disease that affects his nervous system.

His father’s sacrifices have included sleeping on a dorm floor for a night class or carrying his son up a flight of steps when an elevator in White Hall is out of service. He’s on the road to Lexington by 7 a.m. for the 45-minute drive from Garrard County.

“Yeah, we probably go to the doctor a little more than most people do, just because we get him checked out every so often,” Brad Pike said. “But I mean other than that, you know, it’s about as normal as it comes.”

A second diagnosis

Haden Pike was born blind. He can only see light and shadows.

When he was 4 months old, doctors diagnosed him with a retinal degenerative disease called Leber’s congenital amaurosis, said his mother, Teri.

Throughout his childhood, she said, his blindness was a mere inconvenience for him. He was active and played the trumpet in middle school. He enjoyed playing percussion instruments on the sideline in his high school marching band.

But as Pike grew up, his family noticed his balance was becoming worse.

It took about six years to diagnose a second degenerative disease, one that would affect Pike drastically. When he was 16, they found out he had Friedreich’s ataxia, a rare disorder that impairs muscle coordination. Over time, his movement will decline, his mother said.

Her son went from having independence to needing to rely on someone else to take him everywhere. That has been the biggest adjustment for her family, she said. “If you’d known him 10 years ago, you’d be amazed at how different a child he is.”

When Pike realized he wouldn’t be able to walk, he considered two options.

“I can deal with it and keep doing what I’ve always done, even though I’m a little less mobile than before,” he said. Or, he could give up. “So I said, OK, I can’t walk. Who cares? Keep going. And that’s what I did.”

Getting to class

If they’re lucky, Brad and Haden Pike will find an accessible parking spot near Haden’s classroom in the morning. They have a disabled parking permit from the university, but there’s not always spots. If not, they’ll drive around for 15 minutes or so until a spot opens.

His dad parks the truck, unloads his wheelchair from the back and helps him get out. Pike can walk short distances and often does when he goes home every weekend.

This semester, Pike is generally in class at 9 a.m. and done by 2 p.m. Around 10 a.m., if he’s not in class, they tune into Kentucky Sports Radio.

Haden doesn’t like to take notes. He usually sits and listens, then reviews them later on at home.

At least once a week, he visits professors to expand on class topics, take a test or just catch up. He is a computer science junior, whose classes are often visual.

“He has such potential and he is such a brilliant programmer,” said Jeff Ashley, a computer engineering professor who taught Pike last year. “And the family is just amazing.”

Haden and Brad Pike both described Ashley as one of the best instructors Haden has had at UK. Ashley sat down with Pike once a week for 30 minutes to further discuss class concepts. He once printed a map on a 3-D printer so Pike could better understand it.

“He never had a connection because he didn’t have a tool,” Ashley said. “With the printouts, Pike could run his hands over them, feel the patterns and solve the problems just as a student gifted with the ability of sight would do,” Ashley said.

“It was kind of a real breakthrough moment.”

Haden Pike is interested in computer programming and is considering grad school. He also could see himself as a teacher or one day working for a company like Apple to improve accessible technology.

“I got lucky in that my chosen field of interest is computer science because (being blind) doesn’t really affect that,” he said. “And truth be told, it actually gives me an interesting avenue to research things in.”

‘He’s extremely independent’

Pike’s mother said she doesn’t know what her family would have done if her husband didn’t help.

“You do whatever your kids need,” Teri Pike said.

“Fortunately, Brad is able to come over every day and do whatever Haden needs so he can get his college degree.”

Brad Pike worries that he takes some of Haden’s independence away by completing tasks that Haden can do but that Brad can do faster.

“It scares me sometimes leaving him here by himself all the time,” Brad Pike said. “But he’s extremely independent.”

Haden Pike lives in a studio apartment at Newtown Crossing. His sister, Macy, who is a senior at UK, visits once a week with her boyfriend to cook dinner and hang out. His tutor stops by once a week to help with homework.

“He’ll tell you he’s antisocial,” his dad said, laughing. Haden talks to his friends from high school online or by text occasionally, but doesn’t hang out with them much.

“In some ways for him that’s the way he likes it,” Brad Pike said.

Haden Pike spends his time writing about topics he can expand on for nonvisual learners or working on computer programming.

Pike used to read braille, but has gradually lost feeling in his fingertips. Now, he relies on technology to read his calculus textbooks or epic fantasy novels, or to post a status on Facebook.

He said he doesn’t get lonely; he enjoys his privacy.

Brad Pike said he could see his son getting married eventually, and someone else taking over most of the responsibility of helping him get around.

But Brad and Teri Pike know that they’ll always be involved in their son’s life more than most parents, even beyond college. Currently, Haden Pike receives Supplementary Security Income benefits from the government. But his dad said he won’t live off of that.

“That’s our goal — that he can be employed somewhere and make a good living and have a good life,” Teri Pike said.

“Everybody has their own normal, you know.”

‘It’s me and him’

Teri Pike said her husband and son have gotten closer since they went to college together.

Brad Pike said they have a typical father-son relationship. They discuss anything and everything, often making fun of each other or palling around. If there is an attractive girl around, he’ll let his son know.

“We’re together more than anybody,” Brad Pike said.

They have their good days and bad days, and sometimes they get on each other’s nerves.

“Some days you don’t want to go, but you just go,” Brad Pike said.

But he is there every day, ready to take his son to class. After dropping him off, the waiting game begins again for Brad Pike.

“You know, hey, it keeps me busy. Otherwise, I’d be playing golf or something like that,” he said.

But Haden’s dad is his companion.

“I’m not a social person. … It’s me and him,” he said. He says he can’t complain that his dad is always around.

“He really is doing me a favor by just being there every day.”