UNDAUNTED: Double standards

November 10, 2021

In the wide world of sports, gender biases manifest in numerous ways — media attention, resources, revealing uniforms. Many of those threads are exposed by differing expectations for men and women in collegiate sports.

UK players say these double standards are primarily shown in the comments they from media, fans or anonymous strangers on the internet.

“If you’ve gone to Instagram or on a guy’s YouTube, there won’t be a single comment about his form or anything like that,” UK track and field star Abby Steiner said.

But she gets online comments often on her looks, her form and her physicality.

“People will comment about my running form. People I don’t even know, and they’re like, ‘Oh, she runs like a girl who’s trying to be cute in PE class’ or ‘Her form looks like she’s running like a girl,’” Steiner said.

In those comments, running like a girl is used as an insult, but it’s anything but a drawback.

Steiner is the reigning national champion in the indoor 200-meter dash, tying an NCAA record after breaking her own SEC record. Her achievements in sport — including being named a 2020 NCAA All-American and Southeast Region Women’s Track Athlete of the Year — speak to the strength of “running like a girl.”

Steiner finds it crazy that people will comment on videos of high-level athletes and think they know better than the athletes, who have years more experience and elite coaching.

In one comment on a YouTube video of a news segment about Steiner, an anonymous user commented “Hot + Smart + Fast = UK Women Track and Field.” A compliment? Maybe. But “hot” was put first.

In the comments section of Steiner’s 200-meter race at the 2020 SEC Indoor championships — a world-leading time for that season — another commenter said “doesn’t her hair slow her down?”

A third person referred to her as “the Steiner babe” under a YouTube clip of Steiner’s 2021 interview with LEX18.

Comments based on looks is an unfortunately common occurrence, one that often reveals implicit biases.

“Sometimes I’ll get like comments that are like, ‘Oh, you don’t look like a softball player.’ And I’m like, ‘Well, what does a softball player look like?’” UK infielder Lauren Johnson said.

Statements like that show that the world at large has built-in expectations for what women in sports should look like and be like.

“They are commenting all the time on our hair, the way our leotards fit us, every single thing that you can pick apart — our makeup, all of that,” Josie Angeny said. “It’s always super crazy to see the things that you don’t even think people would notice on TV.”

Angeny, a UK gymnast, said comments on men’s appearance are much rarer than those on women. In one gymnastics Facebook group she’s a part of, Angeny constantly sees comments about female gymnasts’ appearances that she doesn’t for men.

“In men, no one really cares. If their hair is super different, maybe they’ll comment on it or say something and they’ll be known for that, but really with girls, it’s like every week I see that with like several different girls,” Angeny said.

The frequency of this critical commentary could make for a treatise on how women’s appearance is more important to outsiders than their athleticism, work ethic or personality. It might suggest that our society values superficial traits like beauty, which in turn is rewarded in ways that encourage increasing attention to one’s appearance.

“They might be giving one girl a compliment and then tearing another one down about it, but in men’s sports, the fans don’t really comment on their bodies,” Johnson said. “We’re looked at for our bodies, whether it’s good or bad, like, ‘Oh, she’s very athletic’ or ‘Oh, she doesn’t look that athletic,’ whereas in men’s sports they don’t really touch that subject — they just look at their physical ability.”

Commentary in men’s sports is more focused on ability, not just looks; if an athlete is big but still fast, the skill remains more important than appearance. Size can be an amusing tidbit instead of a source of mockery.

Whereas a man might be praised for gaining weight or muscle, women are mostly criticized. The peripheral sexism that permeates society as a whole, not just sports, adds an extra layer of concern about body image for women athletes. But size is often valued for its association with masculinity, especially in sports where size is a strategic advantage, like linemen in football — an approach that glosses over the nimble footwork required for such a position.

The valuation of weight in men deviates into body shaming with comments along the lines of ‘what are they feeding him’ and overuse of the word husky by commentators. For men, their height and weight can go either way — worthy of praise or material for jokes. Or, in the case of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, such an unfair advantage that the NCAA bans dunking.

So, athletes in men’s sports are still subject to unfair scrutiny of their physical appearance. Bulking up in the off-season is discussed by the media as one of the key indicators of a male athlete’s improvement from one year to another.

Former UK basketball star Tyler Herro is only one example of this; between his second and third season in the NBA, Herro was encouraged by the Miami Heat to gain 10 pounds of muscle. His ensuing transformation spawned dozens of articles about his physical appearance, with headlines like “Tyler Herro looks absolutely ripped in new gym photo.”

The fact that one Instagram post can spur an entire news cycle speaks to the sports world obsession with looks; Herro is far from the only athlete to garner such a response. See USA Today’s article “Derrick Henry shows off muscles in shirtless Instagram challenge” or the Women’s Health piece titled “Serena Williams, 39, Shows Off Insanely Toned Legs, Arms, Everything In Multiple Instagrams” for further evidence (Williams captioned the photos with a statement about her boots, not her muscles).

Having muscular arms has garnered Steiner many negative comments. UK athletes say they do worry that their musculature and height, traits that give them an advantage on the court, make them less attractive in the outside world, where conceptions of femininity are different.

UK libero Maddie Berezowitz said volleyball players often stand out due to their height and are aware that men don’t see them the same.

“I have teammates who are 6’5” — you don’t even see a 6’5” dude walk down the street very often, much less female,” Berezowitz said. She added that her teammates have also been asked about weight loss.

“I don’t know if that same question would have been asked to their male counterparts,” Berezowitz said.

These double standards can be as hurtful to men as they are to women. Angeny pointed out that rosters, especially in football, often list the athlete’s weight, which publicizes something that maybe should be personal.

Berezowitz also noted that sexism can go both ways. Gymnastics is thought of as a sport for girls, so male gymnasts face sexism in that sport.

“My cousin is a male gymnast, and he kind of gets looked at funny for being a male gymnast,” Berezowitz said.

That commentary on looks and bodies is so widespread in men’s and women’s sports may then be more revealing of a cultural belief that it’s acceptable to appropriate athletes’ bodies than it is on gender discrimination.

Solving the gender biases in these double standards may then be secondary to erasing the notion that fans and commentators have a right to athletes’ persons. Just because an athlete signs up to compete for a school doesn’t mean they’re fair game for criticism, especially of their appearance; unlearning this requires a societal shift in body positivity. If that’s the case, new NIL laws might be a first step in the right direction — putting control of college athlete’s image and name back into their own hands, instead of the proprietary control of their schools.

But though this body commentary is a burden placed on both men and women, the double standard is still there — women receive disproportionately more comments about their appearance, and more negative comments, than men.

According to ABC Australia, a 2019 study found that female athletes received 19 percent more negative comments on online posts than men.

“Of the negative comments directed at women, 23 percent were sexist and 20 percent belittled their sporting abilities,” ABC reported, and 14 percent were highly sexualized.

Women also have to contend with being called manly or masculine for their physical traits, a form of body shaming Serena Williams has faced for years, and one with origins in slavery that highlights how racism and sexism are intertwined.

And for women, the comments extend past just the physical. Though there is no denying that physicality — strength, flexibility, endurance — are foundational aspects of sports, the comments around women often tie those observable traits to intangible ones.

“It’s not just, ‘Hey, your swing sucks,’ there’s always a look comment,” softball coach Rachel Lawson said. “It’s always about what you look like, and that’s always thrown in there somehow. Or if you happen to be a great athlete and you’re attractive, that always gets thrown in there too.”

A study by Cambridge University Press found that men are three times more likely to be mentioned in sporting contexts than women; language used to describe women “focuses disproportionately on the appearance, clothes and personal lives.”

Similarly, broadcasters are more likely to call women “girls” than they are to call men “boys.”

Even the terms used to refer to sports are more overtly gendered for women than men; “we are more inclined to refer to women’s football, whereas men’s football is just called football,” researchers found.

That double standard extends into commentary, Lawson said. Even though some people make personal comments about male athletes, it is almost always personal with women, especially if the woman is not playing well.

Personal comments are just one double standard between men’s and women’s sports. Angeny pointed out a double standard new to the last year — how expectations for mask compliance vary between men and women.

“Men’s sports have kind of been held to a different standard this year with COVID protocols. You don’t really see them getting in trouble for not wearing masks,” Angeny said. “We’re kind of held to a higher standard. We get so many emails from fans if we’re not putting our masks on right away, which obviously everyone should be doing.”

Lawson most sees a double standard in sports in the kind of language men and women are allowed to use.

“I have a bad mouth and I’m really trying to work on it,” Lawson said. “I do things that a normal football and basketball coach does every single day, but a woman, when she speaks the truth in a blunt sort of way, I get a lot of comments on that.”

That principle was on display in the 2021 NCAA basketball championship, when Arizona head coach Adia Barnes was caught on camera saying “f**k everybody” when her team, discounted by many, made it to the Final Four. Backlash was swift, but Barnes stood by her actions.

“I don’t feel like I need to apologize. It’s what I felt with my team at the moment. I wouldn’t take it back. We’ve gone to war together. We believe in each other,” Barnes said. “So I’m in those moments, and that’s how I am, so I don’t apologize for doing that. I’m just me, and I have to just be me.”

Famously potty-mouthed men like Bill O’Brien, Urban Meyer or Rex Ryan are often let off the hook for similar language, which is often characterized as a normal product of testosterone-fueled sporting environments.

“Cussing and football go together like praying and church. From the competitiveness of the sport to its physicality, from drill sergeant-like coaches to the frat-like atmosphere of a locker room, swearing is omnipresent,” wrote columnist Jeff McLane in the Philadelphia Enquirer.

Swearing is thus treated as an acceptable, even amusing, trademark of men that are head coaches, but a flaw for women. Lawson thinks getting to the stage of free speech for men and women is the next frontier in sports equality.

“A woman should be allowed an opinion and she should be able to say it as bluntly as she wants to. But I don’t think that’s the standard,” Lawson said. “I think men are allowed to say things that women just aren’t.”

Instances of unequal treatment differ by sport. Former UK tennis player Akvilė Paražinskaitė said in tournaments, men are more likely to be assigned the more important center court.

“On the bigger scale, it’s getting better with the prize money and stuff equalizing the prize money between women and men,” Paražinskaitė said.

Double standards also emerge in the comparison of men and women. When listing the all-time greats, women athletes are branded as the female version of a male athlete instead of getting their own marker of success.

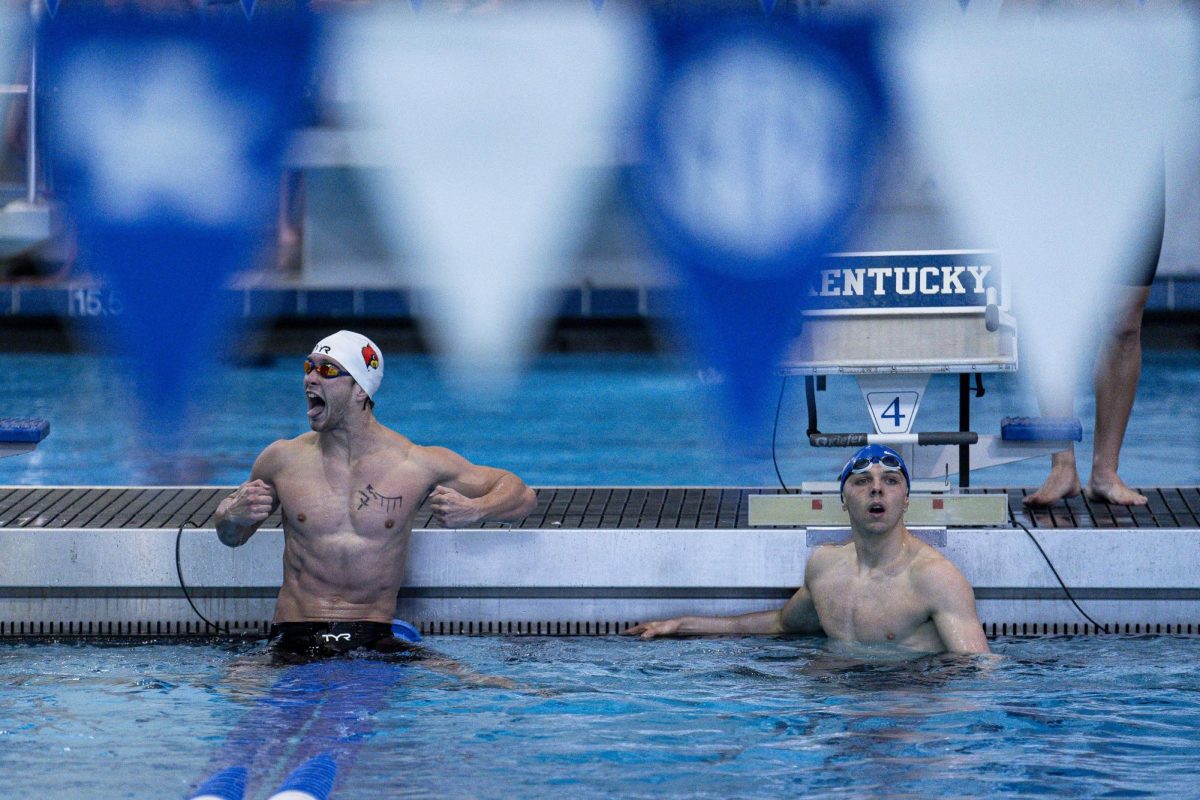

During her first Olympics, Katie Ledecky was branded as “the female Michael Phelps.” Dominant runners like Caster Semenya and Allyson Felix are frequently compared to Usain Bolt instead of the other way around.

These one-way, gender-based comparisons persist despite Felix holding more world record titles than Bolt and Semenya competing in totally different events than Bolt. This repeated method of measuring women’s success only in comparison to men suggests that for society at large, the only framework for understanding women is by their proximity to men, even when their achievements aren’t comparable.

Much of the narrative around Ledecky’s dominance centered on her swimming style — that, as Olympic silver medalist Connor Jaeger put it, she “swims like a man.”

Multiple articles repeated this statement and implied that Ledecky crossing the gender divide in swimming style was the main reason for her success. And though this theory holds water — Ledecky did depart from traditional women’s form in adapting her strokes — she didn’t set out to swim like a man. At the direction of her coaching team, she set out to swim fast, with techniques that anyone could replicate with enough core strength, persistence and mental attunement.

That swimming style is known as a gallop stroke, comprised of longer pulls on the right and shorter on the left, that maximizes “the aggression and the kind of fury that she swims with” according to her former coach Yuri Suguiyama.

But instead of focusing on her intuitive athleticism or hunger to be the best, media and commentators set forth one thing, Ledecky swimming with the same stroke as men, as the core component of her success. Everything else — her precise stroke rate, her work ethic, her commitment to studying film, the mental and physiological flexibility that enables her to dominate both sprint and distance races — was dismissed as incidental, despite being unprecedented in the history of swim.

But that kind of rhetoric, framing women’s success as only existing in conversation with what men do, is more common than it seems at first look. Consider the frequent habit media outlets have of identifying women, even top-performing athletes, by their connection to their husband.

When Hungarian swimmer Katinka Hosszú won gold and broke a world record in Rio in the 400-meter IM, the camera immediately panned to her husband and NBC commentator Dan Hicks said “and there’s the man responsible.”

The Chicago Tribune’s social media post about Corey Cogdell’s bronze medal win identified her as the “wife of a Bears’ linemen” instead of three-time Olympian.

A CBS News tweet about the 2019 Women’s World Cup went viral for focusing on NFL player Zach Ertz instead of Julie Ertz, his wife and the midfielder actually participating in the competition.

The tweet identifies Zach Ertz by name and position while reducing Julie Ertz to “wife.” The focus of the tweet and accompanying article is about Zach missing training camp, not Julie’s success. The attached photo is of the pair kissing after Zach’s Super Bowl win, as opposed to a photo of Julie playing soccer — the fundamental reason the article exists. CBS faced swift condemnation for the misstep.

“’Wife’ is a weird name for a pro soccer player who’s made it to the highest level of her sport,” wrote a Twitter user in the aftermath.

Bloomberg reporter Ryan Beckwith went so far as to point out that Julie Ertz was trending at a higher rate than Zach Ertz at the time, meaning that CBS should have used her name to maximize engagement — a primary goal of news outlets.

Recognizing men solely by their wife’s achievements is equally troubling, though less pervasive.

UK’s own Gerek Meinhardt was tagged as Lee Kiefer’s husband in a People! headline about his Olympic win: “Team USA’s Gerek Meinhardt Wins Fencing Bronze After Wife Lee Kiefer’s Historic Gold.”

That Meinhardt and Kiefer are both successful, repeat Olympians, lessens the sting marital pigeon-holing may incur, especially given that they consider their medals as collective wins. Their commonalities — both medical students, training partners and elite athletes in a shared sport — make mentions of their marriage a logical inclusion in media coverage.

That these mentions go both ways — Meinhardt is listed as her spouse in articles about Kiefer’s wins and vice versa — eliminates a double standard based on gender. Leaving out their relationship would be excluding a part of the story, but that’s not the case for everyone.

Perhaps the treatment of Kiefer and Meinhardt could serve as a model for reducing hypocrisy in media coverage of men’s and women’s sports; only include information about men that you would include about women and vice versa. Better yet, only refer to their spouse if they do so themselves, as Meinhardt and Kiefer do.

The widespread prevalence and extensive variation of double standards in sports makes the issue almost too daunting to tackle. But as UK athletes can attest, identifying hypocrisy in everything from media coverage to trophy size is the first step to ending it — making a better world for us all.

UNDAUNTED, a series by Natalie Parks, explores the intersection of gender and athletics with testimony from UK athletes and coaches. Series installments will discuss body image pressures, unequal access, representation, mentorship and double standards between men’s and women’s sports.