The fate of Destiny: a child’s battle with cancer

September 17, 2008

A year after her cancer’s remission, she hasn’t forgotten her past

With one finger wrapped in her straight, brown hair, she points with her other hand across a grassy field to an inflated slide. “Mommy, I want to go over there.â€

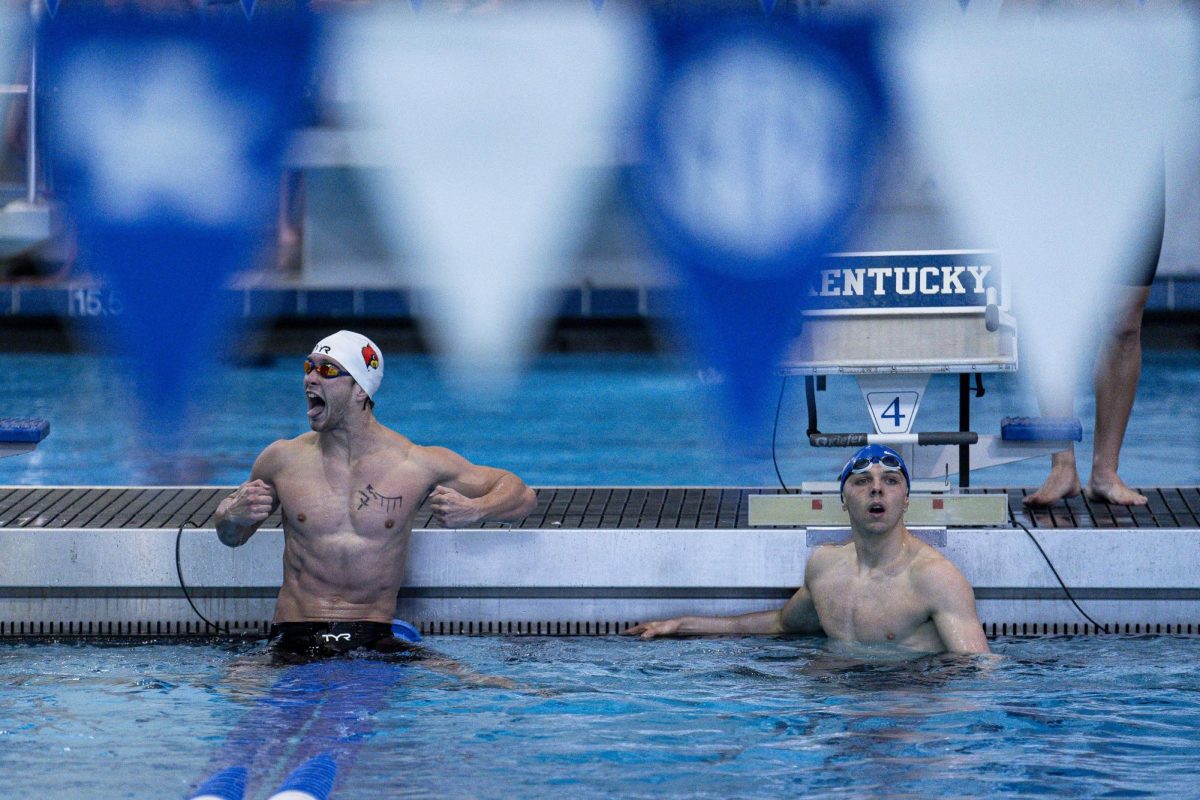

Full of energy, Destiny Ross can’t find enough to do. Mom and Granny try to keep up, arms loaded with free toys, including a firefighter’s helmet and pink sunglasses that Destiny picked out from a basket earlier.

Neither give the slightest mention of “No†or “Slow down.†They’re both just happy that Destiny is able to be at the picnic.

To Destiny, it is about the games, toys and being around her friends. But to her family, it is bigger than that.

Today is the Pediatric Cancer Survivors Picnic. And today they are celebrating her cancer’s remission.

Destiny was diagnosed with stage IV neuroblastoma, a nerve cancer commonly found in children under 5, on Sept. 21, 2006.

Two years later, she is finally establishing the life she had before her cancer. She has returned to school and loves art class. She plays with her cat and loves going to her granny’s house. Destiny never became discouraged throughout the entire process of fighting off cancer. But the fight was difficult.

Destiny is one of many. More than 4,000 children were treated through Kentucky Children’s Hospital Pediatric Hematology-Oncology department last year. Three-hundred eighty of those patients were admitted to inpatient care. While Destiny’s story has been a success, not all are so lucky.

A few months before Destiny’s diagnosis, Regina Ross noticed a difference in Destiny. The talkative, hyper 4-year-old loved to dance, sing and watch television. When she stopped bouncing around the house and became tired all the time, it was clear to her mom and dad, James Ross, that something was wrong.

The family found themselves in the waiting room of their physician’s practice. Visit after visit, everyone was still at a loss for a solution to Destiny’s sickness. Several months of doctor’s appointments came without a diagnosis, and they were directed to Kentucky Children’s Hospital.

A few tests and scans later, the reports came back. Destiny had cancer.

The type of cancer was neuroblastoma, and they were catching it late. Stage IV is at the point that the cancer has already spread through the body, and, in Destiny’s case, into her bone marrow, said Dr. Sherry Bayliff, who has worked with Destiny since she came to Kentucky Children’s Hospital.

Because the cancer had already spread throughout Destiny’s body, the plan for treatment wasn’t as simple as the traditional treatments of chemotherapy and surgery, Bayliff said.

Even when patients are faced with life-threatening diseases, Bayliff said she chooses not to turn to percentages. Every child should be looked at as an individual case and not as a part of a statistic, Bayliff said.

[kml_flashembed movie=”http://www.50.63.25.108/wp-content/uploads/2008/09/destiny/destiny-tonedforweb/cancer_center.swf” height=”447″ width=”590″ /]

“We can say that with neuroblastoma, 30 percent are treated and survive,†Bayliff said. “But we have to consider all children to be in that 30 percent so that we’re striving and trying for a cure.â€

The doctors and nurses in the Pediatric Hematology-Oncology Clinic at Kentucky Children’s Hospital work daily with children who have cancer. Even after seeing thousands of families cope with the reality and possibility of a child’s death, they still aren’t sure there is any way to prepare a parent to hear their child may have cancer.

“We try to be there,†said Jennifer Lee, a registered nurse at Kentucky Children’s Hospital who worked with Destiny throughout her time at the hospital. “We try to listen and be there as much as we can. As for making it easier, I don’t know there is anything they can do.â€

Regina doesn’t think there is anything she could have been told to help her deal with a child with cancer.

“It would have been the same no matter what,†she said. “It’s been rough.â€

Every day the family drives over an hour both to and from their home in Estill County to the hospital. Once they arrive, they typically sit through a day of scans and treatments, and often times have to stay overnight.

Regina had to quit her job at a cigarette company just to be able to do the routine. James had to quit work at the small business he has co-owned for some time. He soon had to go back to work to help pay the hospital bills. That left mom, and sometimes Granny, Donna Noland, to get Destiny to her treatments.

Falling into routine

Just a few months after being diagnosed, Destiny became even sicker. This time, it was a result of her treatments, specifically, chemotherapy.

After thoroughly washing your hands, putting on a pair of disposable scrubs and a mask, you can be cleared to visit Destiny.

In her germ-free room, Destiny watches “The Wiggles†on the television from her bed, interrupted only by the occasional nurse who comes through the door to check in. Her mom is the only unmasked person in the room. She sits to the right of the bed, quietly watching Destiny, not paying much attention to the television.

Despite months of treatments, Destiny is staying positive.

“She likes to try and entertain you and likes your attention on her,†Lee said after Destiny left the hospital. “She likes to sing and dance, and is just your average kid, except, you know, she’s sick.â€

When she’s entertaining, dancing and singing Hannah Montana, you forget she is sick, and forget her beautiful black hair has fallen out. Her skin over her entire head is visible and ghostly pale. It is in her downtime you can see she is tired.

Tired of tubes. Needles. Hospital beds. Just tired of being a hospital-bound, quarantined 5-year-old.

A normal white blood cell count is between 7,000 and 15,000, Bayliff said, and the white blood cells help fight off everyday germs.

Chemotherapy has dropped Destiny’s white blood cell count well below 2,000 cells per microliter, making her extremely vulnerable to even the most common of colds.

“Even a virus someone else would be able to shake off, to a child with cancer undergoing chemotherapy it could be a life-threatening illness,†said Dr. Jeffrey Moscow, a physician who has worked with the family over the years.

Aside from what is expected during chemotherapy, Destiny never caught anything more than a few small viruses that she fought off, Regina said. She was kept in isolation every time she came to the hospital, and at home they had to monitor who came in to the house.

“If anyone had a cold they couldn’t come in,†Regina said.

Looking past the isolation, the most noticeable part of her cancer is her once beautiful, straight black hair is now thinned and falling out from her chemotherapy treatments. All that is left sticks out in every direction, barely creating a brittle, transparent layer of hair over her head.

But what adults notice about cancer is not what children notice about it, Moscow said. Most kids don’t understand what is happening to them.

“Kids get used to the routine,†he said. “They know what the routine is, but they don’t know why the routine is.â€

Destiny never mentions anything about the routine, though. She never complains, or asks what is happening.

“She just got used to it,†Regina said.

Fighting back

She hears some commotion outside her door; voices unlike those of the doctors and nurses she has memorized. The group comes up to her slightly open door, but they are cut off by a floor nurse.

Even Craig Skinner, the UK volleyball coach, and a few of his star senior players aren’t allowed to visit. This patient is in protective isolation, and visitors are limited.

The team is making rounds to all the rooms for Valentine’s Day. Destiny’s mom meets them at the door and they hand over a few things to her.

“What is it?†Destiny says.

It is Valentines and signed posters from the volleyball team. Destiny has to take the gifts and turn down the face time, unless of course the players were to cover their faces with masks and put scrubs on. But even then it is unlikely the nurses would let in so many people to see her. Each person is a chance at another germ getting through to Destiny.

Her mom brings back the cards and spreads them out across the bed. Slowly looking them over, Destiny takes each one and sticks it up to her mom’s face.

“I like this one,†Destiny says, as she picks her favorite out of the group.

Her mom laughs at each Valentine, but more at Destiny’s reaction to them. Despite basically living in a hospital, her daughter is still a cheerful, normal 5-year-old at heart, even with the cancer, the treatments and the isolation. Her spirits have hardly changed at all. Aside from her thin hair and an occasional lonely stare into space, it’s hard to even see a difference.

“She’s been a fighter,†Regina said.

Learning the ropes

After a year of being in the hospital, Destiny has become accustomed to a life of blood tests and the lingo of stem cells and white blood cell counts.

She has quit school because treatments and her poor health make it impractical and near impossible to be around that many children. Her cancer has forced her to trade playtime in the kindergarten schoolyard for her hospital stomping ground. But she makes the most out of it.

“The nurses and doctors love her,†Regina says.

When Destiny and Regina sit down at the Starbucks in the hospital, a group of doctors and nurses sits down nearby. One of the nurses recognizes Destiny and pulls her over for a hug. Another asks if she can have one.

At first Destiny pulls away and hides behind a chair. But after a few moments of peeking over the chair, Destiny jumps from behind the seat and runs out to give them all hugs.

She feels like she’s part of the hospital. Part of the family. Sure, there are hundreds of other sick kids in the hospital, but each nurse and doctor, whether they know the patient or not, is there to try to save the lives of every single one.

Despite the reality of their jobs, Destiny is just having fun, and it doesn’t stop her from feeling at home.

A few months later a volunteer at Kentucky Children’s Hospital comes in Destiny’s room with paper and paints, and Destiny is allowed to pick out her colors.

“Pink,†Destiny says. She takes a few others, and then spreads out her supplies on a table.

“What are you going to paint?†the volunteer says.

After a little hesitation, Destiny knows exactly what she wants. “A flower,†she says, dabbing her brush in her pink paint.

She is giving all her attention to her artwork, only occasionally looking away to the television. With a few stray brushstrokes on the edges of the paper and several splashes of spilled paint, her efforts are slowly paying off. A flower is starting to come together.

A nurse comes in with some equipment rolled up in her hand. Destiny briefly stops working on her flower and sticks out her right arm and pulls up her sleeve.

“It’s time to take my blood pressure,†Destiny says.

The nurse slips on a blood pressure gauge, and Destiny ignores the rest of the process. She redirects her attention to her painting and doesn’t take her eyes off her artwork after that.

When she had been in the hospital for three or four months, Destiny knew the ropes. She knew what an IV was, where the labs were, what they do in the labs and what stem cells were.

“Now if we go there, she tells them what we have to do,†Regina said.

Extraordinary opportunities

Destiny is enjoying a normal life.

Now 6 years old, she is full of energy again and her hair is growing back. It’s a little fuzzier than before and has changed from black to brown, but she is happy to have it back. When her dad told her she needed to have her bangs cut, she said, “You want my head shaved like it was before?â€

When her hair started to grow back, Destiny began to play with it all the time. Twirling it, pulling at it. She never stopped. For a while she was accidentally pulling her new hair out. Mom and Dad were finally able to get her to leave it alone. Now, she just twirls it.

When asked what she missed most while she was in the hospital, Destiny takes no time in shouting back, “My cat.†But right behind her cat is a close tie between “playing with my Barbies†and “seeing my daddy.â€

Destiny’s life in remission of her cancer is celebrated, but through the hospital, she experienced a few great adventures.

Destiny was chosen by the Make-A-Wish Foundation to go to Disney World. Destiny, Regina and Granny Noland all packed up and went to Orlando, Fla, for four days and four nights. Despite a fear of all of the characters in costume, Destiny had a great time, Regina said. When a pair of Hannah Montana tickets were donated to the Children’s Hospital, they gave them to Destiny, too.

Regina said Kentucky Children’s Hospital was the best place she could have taken Destiny.

“I wouldn’t have taken her anywhere else,†Regina said.

Nurse Lee says it’s hard to work with kids this sick all the time, and even harder to see the ones who you know are not going to be as fortunate as Destiny.

“It’s hard to go back and see kids that are sick and in pain, and ones that aren’t going to make it,†Lee said. “But I try to focus on the ones that are there before me. Every hematology and oncology child that we deal with has such a love of life. For the most part they’re not depressed. They’re not sad. They’re just kids.â€

It could come back

When Destiny visits the hospital now, it’s usually not to get an IV or for an overnight stay. She has been in remission since September 2007. She goes for scans every three months. Eventually, her treatments will go to every six months, then once a year.

But even though the cancer is gone, it is not over.

“It’s scary because they told me she could go in remission for six months then relapse,†Regina said.

After a scan, when the results don’t come in exactly when they are supposed to, Regina begins to wonder if something is wrong.

“You wonder what’s taking them so long,†she said.

Even when Destiny doesn’t have to be at the hospital for tests or checkups, Regina finds herself taking I-75 North to Lexington and pulling into the parking garage at Kentucky Children’s Hospital.

“She likes to come and visit,†Regina said. Not just to visit the doctors. Destiny has other friends from the hospital. Other patients.

One of Destiny’s friends has the same type of cancer, and they have spent two years together at the hospital.

“She got really close to him,†Regina said.

When her friend was first sent to the hospital, doctors asked Regina to speak with the mom.

“I knew what she was getting ready to face,†Regina said. “It felt good to talk to her about it.â€

But now Regina finds herself uncomfortable when talking about their friend’s cancer. His cancer relapsed several months ago.

Dealing with the good and the bad is a healing relationship no matter the outcome, Bayliff said. In the end, the families who lose a child are still a part of the hospital’s family.

“It’s worth the tears and the heartache, even if it’s just for 10 more minutes for a family to get their little one to hug and hold,†Bayliff said.

Destiny hasn’t forgotten her past or those hardships. At the end of every healthy day of her life, she prays for her friend before going to sleep.

“It would be really hard for her if something were to happen to him,†Regina said.

The mother of the friend tells Regina that Destiny is an inspiration to her and her son for her will and her faith. But inspirational or not, Regina still feels guilty over her own daughter’s health.

It makes you not want to talk about how well your kid is doing, Regina said.

A celebration

Today, Destiny is doing well.

Today is the Pediatric Cancer Survivors Picnic. And Destiny is celebrating her cancer’s remission.

Having played almost every game and gone through every inflatable slide and obstacle course available, Destiny slows the pace and decides to get her face painted. DanceBlue an annual UK fundraiser for cancer, has two volunteers with brushes and face paint.

Destiny waits patiently in line, watching as a volunteer finishes up a ladybug on the little girl in front of her. Another boy proudly shows off his new alligator on his cheek to his dad.

It is Destiny’s turn. The artist asks her what she wants, and she points to the DanceBlue logo on the table.

“You want the DanceBlue logo?†the volunteer says. Destiny nods.

After a few minutes and several strokes of blue and yellow watercolors, it is over. With cherry sno-cone smeared on one side of her face and a perfect DanceBlue ribbon on the other, Destiny is ready for another activity.

“What did you get?†her Granny says.

She points to her left cheek with one hand, twirling her hair in the other.

After all, today Destiny is doing well. Today, she is a survivor.

Related Articles:

‘Exceptional’ staff making the difference at Kentucky Children’s Hospital