Thrill of the Hunt: Lexington fox hunting club preserves a centuries old tradition

December 3, 2019

Just a half hour’s drive from the bustling, cell-phone ringing, e-scootering UK campus, the steady plod of dozens of former race horses could be heard marching over a babbling creek deep in the rolling farm hills of southern Fayette County.

Smiling riders, wearing bright red, gray and brown coats, topped the thoroughbreds and all marched through the early November, fall-colored trees to a picturesque red and white mill nestled on the creek. All were on their way to a sermon.

All were a part of the Iroquois Hunt Club—the nation’s third oldest fox hunting club and a Central Kentucky tradition that preserves a centuries old sport that still connects people to the land and to animals in ways that are often scarce in Lexington’s growing and digitizing urban downtown.

Lilla Mason, the huntsman and joint master of the hunt club, leads over a dozen English fox hounds before a gathering crowd and orchestra in front of the mill. Dressed in a red coat with gold buttons and black protective riding cap, Mason and other masters of the hunt address the crowd of a few hundred well-heeled locals as she fends off the happy protests for treats and attention from the hounds.

“They get to use their God-given skills to do what God made them to do,” Mason said of the hounds, while brandishing dog treats in her white-gloved hands. “It’s wonderful to get to experience that and watch them work.”

After Mason spoke, the Rev. Charles Ellestad of St. Hubert’s Episcopal Church addressed the crowd in a sermon that would conclude with him blessing the riders, the hounds and praying “for the prey.” The blessing is an annual tradition for the club—which was established in the county in 1880.

After the blessing, the hunters embark on a hunt, following the noses of the hounds through rushing streams, over green hills and through the red, yellow and brown-colored forests.

“We pray for all creatures great and small who fill this land with life. Give us all the wisdom and will to protect this treasure,” Ellestad said. “We pray also for today’s prey, those wild and wily coyotes, without whom the thrill of the chase would not be possible.”

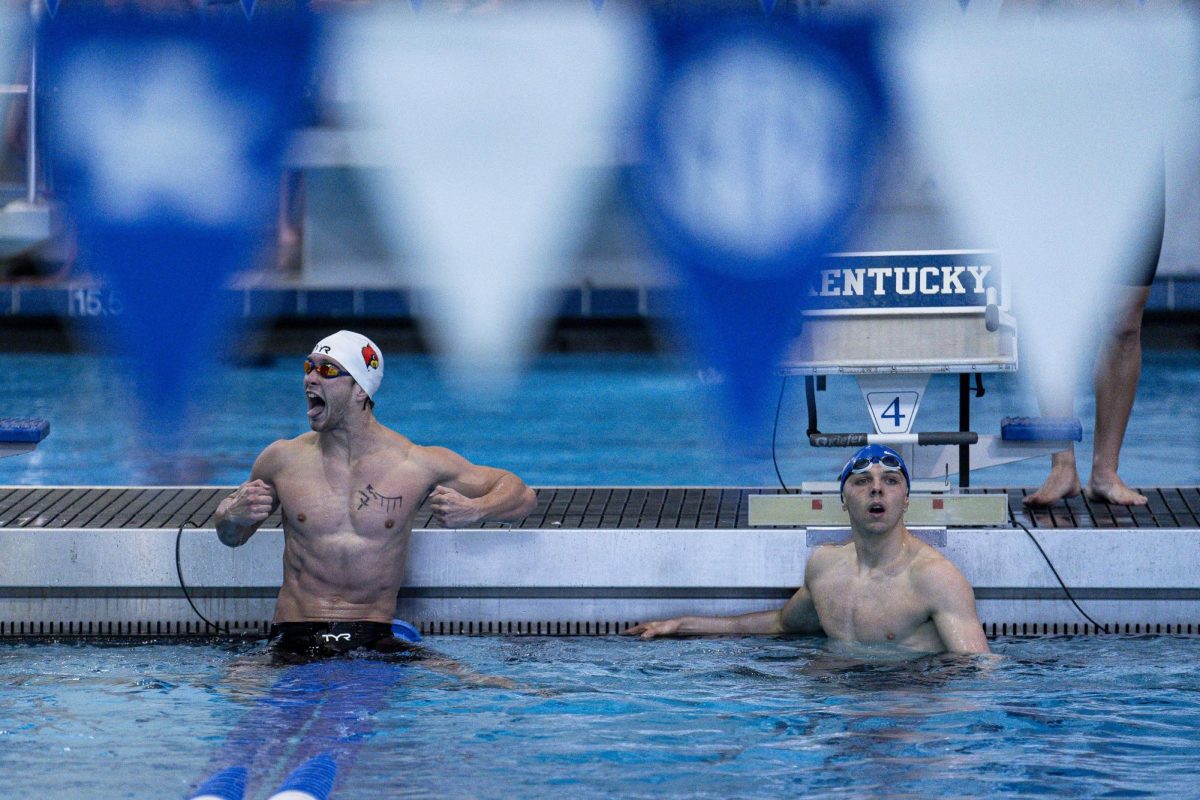

THE THRILL OF THE HUNT

Tails wagging, noses to the ground a group of hounds inspected a field of grass in mid-October. Riders on retired thoroughbreds waited at the top of a nearby hill as Mason blew on her short, but loud hunt horn, to urge the hounds on.

Mason’s voice crackled on a walkie-talkie that sat inside the all-terain vehicle which ferried around Kernel reporters while they observed the club for a few months this fall.

“That’s good hound work,” Mason said over the radio. “They’ve picked up the smell again.”

One hound let out a loud yelp, while the rest of the pack of about a dozen dogs, followed closely behind noses still in the grass. Mason inched down the hill closer to the pack, her horse picking up speed.

“Your horse’s heart starts pounding because he knows pretty soon he’ll be galloping,” Mason said, later explaining the moment in an interview. “Another hound will speak and pretty soon, it’s this symphony of loud voices.”

Another hound soon cried out. Then another, and eventually the whole group in unison began charging through the field, letting loose a deafening howling cry over the quiet countryside.

The company of retired race horses followed the hounds, thundering through the field and into a nearby forest—the ground rumbling like the starting gate at Keeneland.

A former thoroughbred’s athleticism becomes very important in this moment, Mason said. Galloping over natural ground requires a sure-footed horse.

“He might jump a hole or jump a creek,” Mason said. “…It’s just so much fun. It gets your adrenaline up.”

“Everthing’s unscripted,” Mason said. “You’re hunting live animals with live animals. Every day is different.”

Aliina Keers, the club’s kennel huntsman, told the Kernel that seeing hounds track a live animal hooked her into the sport.

“You feel it inside you, you’re just so joyous,” said Keers of following the hounds while galloping behind on horseback. “The wind streaming by your face, the tears running down your eyes.

“It’s just really really incredible, and I thought I just got to do this all of the time. As much as I get this feeling, I need this.”

THE PREY

It’s no secret that the fox-hunting club does not hunt foxes, Mason said in an interview with the Kernel. The club does not catch and kill coyotes, they only try to scare them off and keep them disorganized, Mason said.

Foxes haven’t been able to widely populate rural central Kentucky since the late 80s, she said, when packs of coyotes began to filter into the area from the west.

“They decimated the fox population,” Mason said. “For the first time the foxes had more of a predator.”

In the past, Mason said, the hunt club used native-to-Kentucky fox hounds who could keep foxes from eating farmer’s chickens and terrorizing the barnyard. Now, the club uses rangier English hounds with greater stamina to drive the coyotes, who are larger and more athletic than foxes, out of the area and unable to harm livestock and house pets. The local farmers, Mason said, let the club hunt on their farmland during the fall and winter.

Aside from the change of prey, the club has stuck to the traditions of a sport that has allowed men and women to ride side-by-side for centuries, said Mason who has been a part of the club since she answered a Kernel help wanted ad to exercise hunting horses in the mid-80s.

Originally a show-jumper from El Paso, Texas, Mason said she came to UK to finish college and was drawn to the club’s challenging, all-terrain horse riding. She eventually grew fond of the hounds and the sport.

STUDENTS CAN GET IN THE HUNT

Keers, who hails from Washington state, said she’d been riding horses since she was 7. She works at the club full time and mainly manages the club’s animals, which includes 11 hunt horses for staff members and all of the dogs. She said while learning to ride as a kid she’d go on the occasional hunt.

“But I didn’t really get into it,” Keers said. “It didn’t occur to me that it was a potential job until, well, I graduated from college.”

After college, as part of an international exchange, Keers was able to go on multiple hunts in England and Ireland. But when she returned to the U.S., she first got an office job in downtown Boston, but she missed fox hunting.

“I’d still rather be outside in 15-degree weather than sitting at a computer,” Keers said. She started volunteering and working at hunt clubs in Massachusetts and moved to Kentucky when a job with the Iroquois Hunt Club opened up.

Both Keers and Mason said they want more UK students to get involved with the hunt.

“It’s a lot of fun, it’s a really good opportunity for anyone who enjoys riding and doesn’t necessarily have the financial capability of keeping their own horse,” Keers said.

Like she did over 30 years ago, Mason said she wants students at UK who have strong riding experience to come out to the club to exercise some of the hunt horses.

“Where else would you get to do this? I mean, why not experience it? It’s so much fun,” Mason said.

“I remember being in West Texas, I thought one day before I die, I’d love to be on a fox hunt, that’d be on my bucket list,” Mason said. “I never dreamed I’d be doing it all the time.”