Discussions of politics always seem to be more contentious during the presidential election years. This has been especially true since 2016 when scandals abounded about the candidates of the main two parties and the eventual outcome made long-standing political rifts wider and deeper.

Although I would not say that that election was quite as exceptional as many treat it, it was remarkable for how severe the disparity between the popular vote and the result produced by the Electoral College was. Hillary Clinton, despite winning the popular vote by a margin of almost 3 million, did not win the 270 electoral votes necessary to win because of how the votes were distributed across the country.

Donald Trump’s victory in the election has invited much analysis, interpretation and explanation. The most pragmatic is that he out-campaigned Clinton in the Great Lakes states of Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania winning the electoral votes of those states by narrow margins and securing the electoral votes needed to win.

Those who have pointed fingers in the years since have been inclined to consider third-party candidates—principally Jill Stein, the candidate for the Green Party in 2016, as the culprits for Clinton’s loss in those three states, since they received thousands of votes that supposedly would have gone to Clinton otherwise.

This leads many to conclude that third parties undermine democracy by putting up “spoiler” candidates that split coalitions and enable opposing parties to claim victory.

While there is no shortage of problems with the system of democratic governance in the United States—the convoluted Electoral College, gerrymandering and the practice of lobbying —the presence of third parties is not one of them. In fact, the success of third parties, by offering voters more candidates with more diverse platforms and undercutting the duopoly of party politics will make the country more democratic.

Historically, the American political system has generally only had room for two parties that compete for power. The current dichotomy of Democratic vs. Republican has only existed since the end of the Civil War, and the dynamic of these two parties has changed significantly between then and now.

Whenever parties other than the big two have gained prominence, it has not been for very long, nor have they had much to show for it. When Theodore Roosevelt ran for a third term as president in 1912 under the Progressive Party, he drew votes away from the incumbent, former President William Taft, and enabled former President Woodrow Wilson to win the electoral vote.

In the 1912 election and several elections since then, the presence of a third-party candidate effectively undermined the candidate more closely aligned with them and gave the party opposite to both of them the edge. Democrats have accused candidates for the Green Party of doing this since Ralph Nader ran in 2000 and with Al Gore narrowly losing to former President George W. Bush.

It is undeniable that third parties face a structural disadvantage in the electoral system in the U.S. While the Green Party has successfully run candidates in local races across the country, it has never been able to win any share of the Electoral College votes since states generally award their entire slate of electors to the candidate with the most votes in the state. Given this obstacle, most people regard third parties as a waste of a vote, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy.

However, a third party’s accomplishments might not always be as direct as winning elections. Ross Perot ran in 1992 on a platform of reducing the federal budget deficit, and he was successful at creating the perception that this was a major issue.

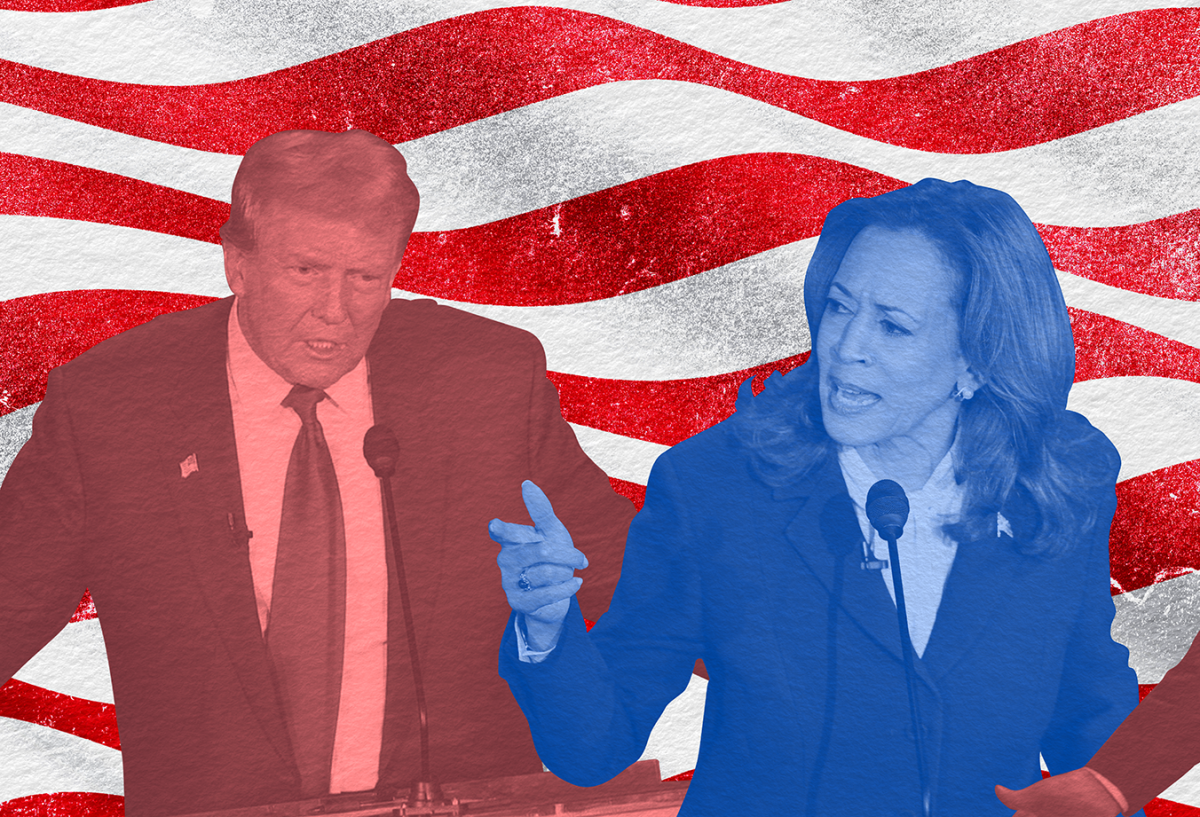

More recently, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. filed to run as an independent candidate in the 2024 presidential election, offering a platform most prominently concerned with his skepticism of health science that had more appeal with likely Trump voters. He has since dropped out of the race and endorsed the Republican nominee, and it appears that he has secured a position over public health in return for his support.

Both Perot and Kennedy have exerted influence over the politics of the Republican Party by running campaigns that appeal to its voter base and forcing the party to engage with their ideas. It stands to reason that a party appealing to the Democratic Party’s base of support would have similar leverage to force policy shifts.

I admit this is a much more distant possibility than what Perot and Kennedy accomplished with Republicans. The Democratic Party has proven more effective at resisting leftward pushes from within its ranks than accomplishing its stated policy goals, and they have happily used left-wing candidates like Stein as scapegoats to cover the weaknesses in their campaign strategies.

That being said, the ascendance of other parties to greater prominence in American politics inevitably forces politicians to be more responsive to public opinion than they are now. One could think of politics as a market. Such as increasing competition is good for consumers, as it forces producers to cater to their needs or risk losing their business.

As it stands, the Green Party, once again running Stein as its candidate, has the most potential to disrupt the current duopoly in politics. Its platform includes several policy proposals that fall far to the left of the Democratic platform, the most notable being a commitment to restricting military aid to Israel. Given the popularity of this proposal, the Green Party has reasons to be optimistic about their performance.

Third parties are subjected to plenty of mockery and scorn for their inefficacy in politics. Critics of the two major parties accuse them of undermining their respective candidates and indirectly supporting their ideological rivals. For some elections in American history this has been the case.

But party politics in the present moment is due for a shakeup. I look forward to seeing it play out in this election.