SAD winters: Seasonal depression affects some UK students

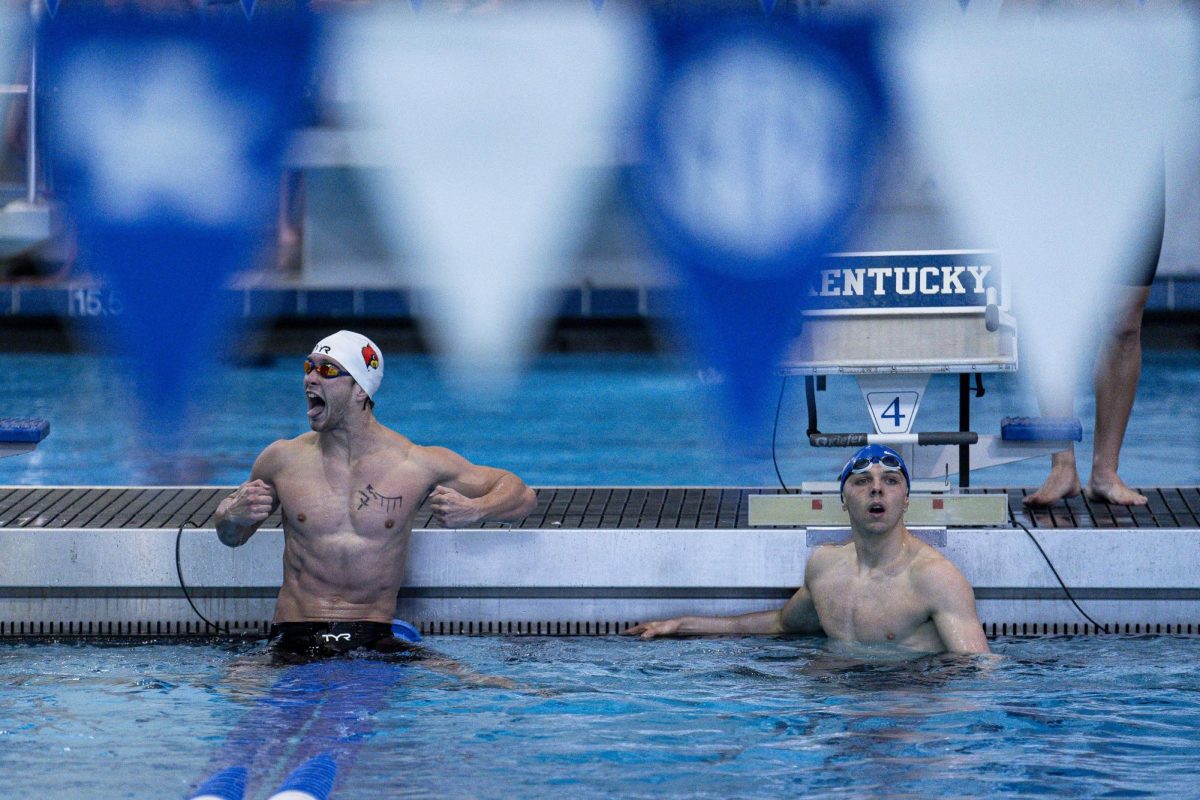

UK freshman Zoey Drexel sits in the Gatton Student Center with Scooby, a 4 Paws for Ability dog, on Friday, Jan. 27, 2023, in Lexington, Kentucky. Photo by Travis Fannon | Staff

February 3, 2023

Windy, gray and freezing cold — that’s been the trend for January weather at the University of Kentucky.

When walking to class feels like crossing the Arctic tundra, it can be especially difficult to get out of bed for some students.

Sufferers of seasonal affective disorder (SAD), defined by the American Psychological Association as “a type of depression that lasts for a season, typically the winter months, and goes away during the rest of the year” have been struggling on campus lately.

According to Matt Southward, research assistant professor of psychology at UK, symptoms of SAD include general sadness, oversleeping, fatigue, lack of energy and motivation, self-isolation, lack of interest in usual passions, overeating and, in extreme cases, suicidal thoughts.

Southward said the causes of SAD are not certain but are thought to be primarily a combination of biological and environmental factors, whereas common depression is often brought on by stressors in people’s lives.

Shorter days and less sunlight may trigger a chemical change in the brain. Other factors that may come into play include vitamin D insufficiency and confused circadian rhythm from the lack of sunlight, Southward said.

SAD is more severe than the average person’s tendency to feel down when the weather is unpleasant.

“It’s when it starts to be that level of impairment,” Southward said. “It’s making it hard for you to do the things you care about, to be with the people you care about, to function in the ways you want. That could be a good indication that you’re experiencing a clinical condition rather than the pretty typical slowing down that happens.”

Katie Mushkin, sophomore at UK, was diagnosed with SAD her senior year of high school and said her feelings of impairment start around November of each year.

“It takes away a lot of my motivation and my energy,” Mushkin said. “I find myself less willing to do things. It’s harder to get out of bed, go to my classes, do things with my friends or want to go out.”

This is out of character for Mushkin, who is vice president of recruitment for her sorority Phi Sigma Rho and spends her summers counseling a summer camp.

“I work at a summer camp and have to be at work by 6:45 (a.m.), and it was so much easier for me to do that than it is to even get up on the weekends and get lunch or something during the winter,” Mushkin said.

Freshman Zoey Drexel’s SAD also makes it difficult for her to get out of bed despite her love of being outdoors.

In the winter, Drexel misses being able to get fulfillment from spending time in nature. She hopes to work in a national park one day.

“I find happiness outside. Being outside is one of the biggest things for me. And when it’s colder, it’s just not as enjoyable,” Drexel said. “So that definitely makes it more difficult just to get going. Once I’m up, it’s easier, but like, I just want to be in bed all the time.”

Each winter, Drexel finds herself caught up in a cycle many with SAD can relate to. She doesn’t have enough energy to get out of bed and hang out with friends, but because she isn’t seeing her friends as much, she misses the energy she usually gets from them.

“So when I’m having a more depressive episode, I tend to self-isolate and cut off those friendships,” Drexel said. “Being the extrovert I am and how I prosper off of friendships, it’s harder to do as well when I’m not taking care of myself.”

Mushkin also sees her friendships impacted by SAD.

“It’s hard to make myself want to go to the library or go out with my friends,” Mushkin said. “So I find myself canceling plans a lot because I just have no energy to go do things. I spend less time with them and sort of pull away.”

Drexel said her grades tend to suffer during the colder parts of the semester because of her low motivation. She also has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which doesn’t help mediate the effects of her SAD.

ADHD makes remembering and completing tasks difficult on its own, so the combination of ADHD and SAD can be especially hard to manage. Southward said a combination of disorders can make the manifested symptoms stronger.

“You start adding other disorders on it and they start to multiply their effects,” Southward said. “If you add anything to (SAD), it will probably exacerbate it.”

Mushkin also experiences exacerbated effects of SAD due to her anxiety.

“I think the anxiety makes the SAD worse because when I get anxious about something during that period, it tends to be a lot more debilitating than when I am otherwise in a good headspace,” Mushkin said.

Southward said college-aged people may be at increased risk for SAD. SAD occurs in 5% of the U.S. population and most commonly starts in young adulthood (ages 20-30) according to Mental Health America.

Having dealt with SAD since high school, Mushkin said it has worsened since coming to college.

“I think college was a lot worse because I wasn’t living at home, I was spending more time by myself and I was having to be outside a lot more, so I had to deal with the weather a lot more than when I was living at home and being inside at school all day,” Mushkin said.

There are many ways SAD can be combated, varying in effectiveness from person to person.

Southward said SAD can be treated with cognitive behavioral therapy, sunlight replacements like vitamin D supplements and light boxes and psychotropic medications.

For college students specifically, Southward suggested that a consistent sleep schedule be established. He said students should try to wake up at the same time every day to balance their circadian rhythm and maximize energy in the dreary winter months.

Southward also said students should try and socialize even when it’s hard to go outside.

“Really rely on that social network,” he said. “Plan activities, commit, say, ‘Hey, it does feel crappy out, but let’s do something together.’ I think that social activity can have a really nice buffering effect during these kinds of months.”

Mushkin and Drexel both said that seeing their friends helps them feel better even on days they woke up feeling antisocial.

For Mushkin, sticking to a schedule and focusing on “the little things that don’t necessarily depend on the season” help the most.

“I find it better to have little things to look forward to,” Mushkin said. “I love being able to wear shorts and T-shirts when it’s warm, so I’ve tried to pick out a cute outfit that I want to wear that’s suitable for the cold weather and would make me feel better about being outside when it’s not feeling great.”

Drexel is a primary caretaker for a 4 Paws for Ability dog and said that having a constant fluffy companion is an effective coping mechanism. The responsibility of caring for her dog gets her out of bed and her dog’s energy improves her mood.

“(The dogs) are so good and it’s really easy to say, ‘Oh you’re antsy? Okay, time to get up and move,’ and just get the blood flowing,” Drexel said.

While SAD looks different for everyone, Southward offered advice all sufferers of SAD and other mental illnesses can use.

“With depression, it is really easy for us to blame ourselves or to feel like ‘I can’t do things, so it must be my fault.’ Recognize that this is something that is not uncommon and it’s not a personal failing,” Southward said. “Be compassionate about ourselves, and then extend that to each other.”

For mental health support and resources on campus, visit https://www.uky.edu/counselingcenter/.