Difficult conversations: How to start and finish them

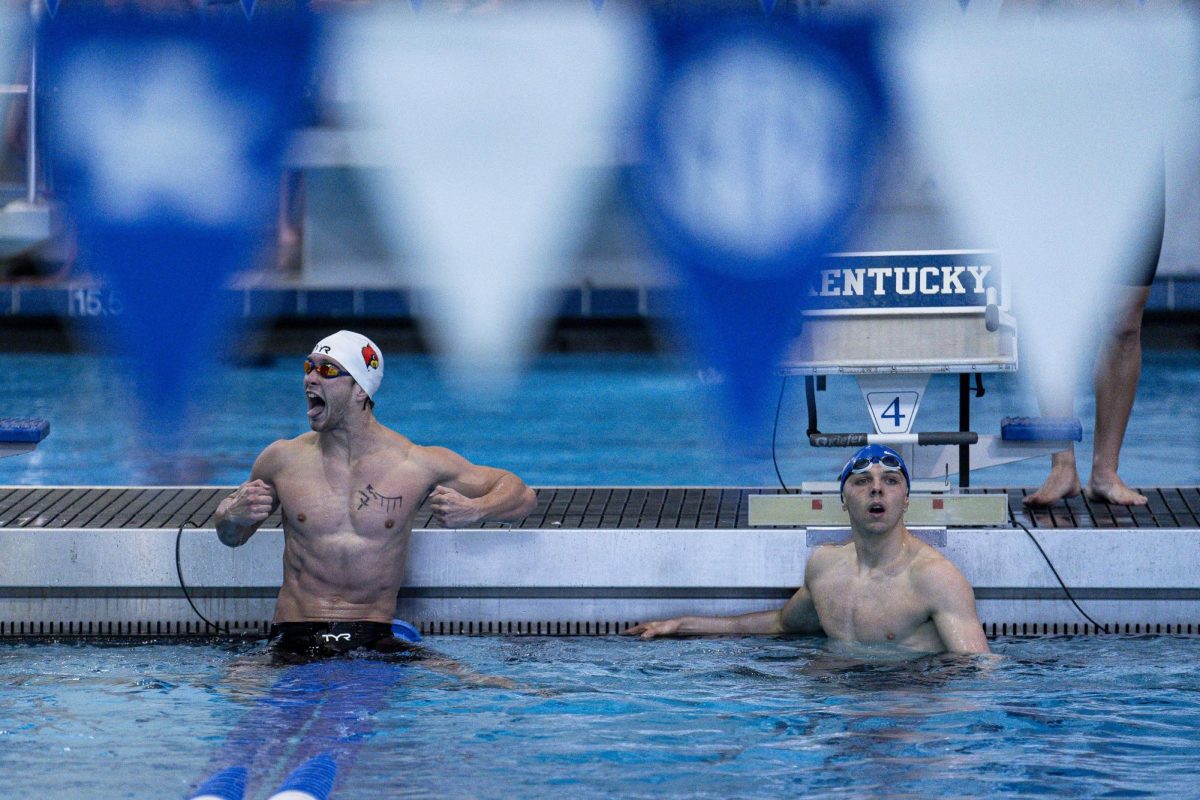

Lewis Honors College at the University of Kentucky on Friday, Jan. 29, 2021, in Lexington, Kentucky. Photo by Jack Weaver | Staff

November 23, 2022

Silence filled the lobby of the Lewis Honors College as a student broke down into tears. The student was attending a Lewis Honors College event promoting “Solid Ground,” a book written by Tom Lewis, that has been the subject of controversy ever since it was first handed out to students in 2020.

While UK has had an honors program since 1958, Tom Lewis’s donation established the Lewis Honors College, and the building was named after him.

During the Q&A portion of the event, the student told Lewis how his book, which said there are only two genders, denied their humanness and existence.

Lewis apologized.

More students raised difficult questions: why has he donated to the anti-LGBTQ+ group Alliance Defending Freedom? Why has he included a sentence in his book that reads, “during the Civil War, much of the Confederate Army was made up of Scots-Irish descendants who fought with ferocity and bravery?” Why did he correlate anxiety and depression to a lack of Judeo-Christian values?

Lewis Honors College Dean Christian Brady ended the book promotion event reaffirming the Honors College’s support of students of all backgrounds and perspectives, and said the honors college will “continue these conversations as we go forward.”

It is hard to have difficult conversations. Even harder is turning these difficult conversations into concrete action.

But it is naïve to believe that difficult conversations are avoidable.

“I am working with colleagues across campus to launch a series of speakers and conversations on the subjects of free, responsible speech and academic freedom. This will begin in Spring 2023 and continue through the next academic year,” Brady, who declined to meet for an interview, wrote in an email. “Concurrently, we hope to develop discussion groups that will read together and meet to continue the conversation.”

Instead of launching a speaker’s series on free and responsible speech, I believe that a town hall where students can bring up concerns directly to the administrators would be more productive than having speakers talk about how to talk about difficult topics.

Just let the students talk, and then listen.

“The questions we asked were challenging but largely in good faith. We weren’t trying to rip down (Lewis’s) reputation. We were just trying to get answers and have a conversation that we weren’t getting otherwise,” Mack Thomspon, a Lewis Honors College student who attended Lewis’s book promotion event, said.

Dylan Myers, an honors college student who raised questions at Lewis’s book promotion event, said that it is essential to assume everyone has good intentions when having difficult conversations.

“You have to assume that when somebody says something, it’s not because they’re trying to hurt you,” Myers said. “Even with Lewis, I could tell that he was trying, but he didn’t have the knowledge to actually make that step and bridge that gap.”

Most students already understand the principles of free and responsible speech. What is lacking are safe spaces that can facilitate an equitable exchange of differing beliefs – and safe spaces where student concerns can be raised and acknowledged.

“I’m not sure that I would call this (Q&A session) a conversation because I do not think it was an equitable exchange. Lewis is a powerful man whose name is on our building, as our donor,” Zada Komara, a lecturer in the honors college, said.

Speaker series are not open conversations. Such events are one-sided in favor of the speaker and whatever views that speaker holds.

Why not launch open town hall forums where students could speak on an equal basis with administrators and donors? Or open discussions where students can speak to other students, faculty and staff?

Rachel Whitehouse, a senior in the Lewis Honors College who also attended the event, said that she would like to see more open discussions where a diverse group of students could meet with administrators and donors in a comfortable setting.

While she acknowledged that it is not possible to have one conversation change the way campus is run, during those conversations administrators should listen to student voices, respond to them and consider student voices when making decisions.

In an interview, Lewis said that he would not object to having an open conversation with students about difficult topics.

“I’m not object(ing) to that, but I also don’t wanna walk in to get slaughtered by a group of people that want to argue with me,” he said.

So, what would a safe space to hold such conversations look like — whether it be with administrators and donors or other students, faculty and staff?

“Having someone that’s moderating, I think would also be something great. But I think the biggest is the disposition of the people having the conversation. If they’re not making this a battle, but more of working together to figure something out,” Michael Morgan, a Lewis Honors College student, suggested.

For the moderator, Myers said that it is important that such conversations are led by people who are open about their knowledge of systemic issues.

As for the way conversations should go, Komara brought up a strategy she teaches students — dialectical behavioral therapy.

“During any kind of conflict over values or morals or ethics, we should all try to find something valid in what the other person is saying. Just one thing, and you don’t have to agree with them at all. That is not the point. The point is to recognize the other person’s humanity,” Komara said.

But this does not mean that a good conversation is defined by a robotic exchange between two parties. It is important to recognize that difficult conversations are difficult because the topics brought up are oftentimes deeply personal, no matter what views an individual holds.

Myers said that together with other people from all backgrounds, they would like to be able to have a frank conversation with administrators and not be expected to mince their words.

“I guess because respectability politics only gets you so far, and I think that it should be open to people expressing all sorts of different emotions,” Myers said. “Because this is something that can make you start crying or want to yell, or something like that, and I think that there should be space for that.”

Lewis reflected on the Q&A during the book event and commented that when the student started crying, it helped him to understand that their raw feelings were genuine, and they were not pretending.

In a safe space, no one should feel afraid of expressing their views and their emotions. Everyone should be allowed to do this with the understanding that at the end of the day, even with differing opinions, they are acknowledged and respected. And the resulting conversation should broaden their world view, and challenge each individual’s biases.

“This is how I have difficult conversations with students over issues like abortion rights and abortion access. You know, if they have a religious view that states that abortion is a sin, that’s their view. I’m not here to change their faith, and I think that their faith is beautiful, and I think that their commitment to human life is beautiful,” Komara said. “And I’ve had this conversation with students who have said to me like, ‘Well, I see what’s valid in your point. You think that women should have control of their own bodies, and I think your feminism is beautiful.’ And when we have that sort of exchange, the dehumanization is really no longer possible. And so I hope that conversations in Honors can unfold like that.”

As for the Lewis Honors College, I think a great first step would be to recognize the humanity of your students, create a safe space to listen to their concerns and then work together to find a solution.

Have faith that your students are not looking for an argument or to slaughter anybody – they are asking to be loved for who they are.

Dylan Mears • Nov 23, 2022 at 11:31 am

i love this!!! i hope we can actually start having these sorts of conversations soon. thank you jemi for your time in the interviews <3

<3