Professor teaches 5 classes without speaking

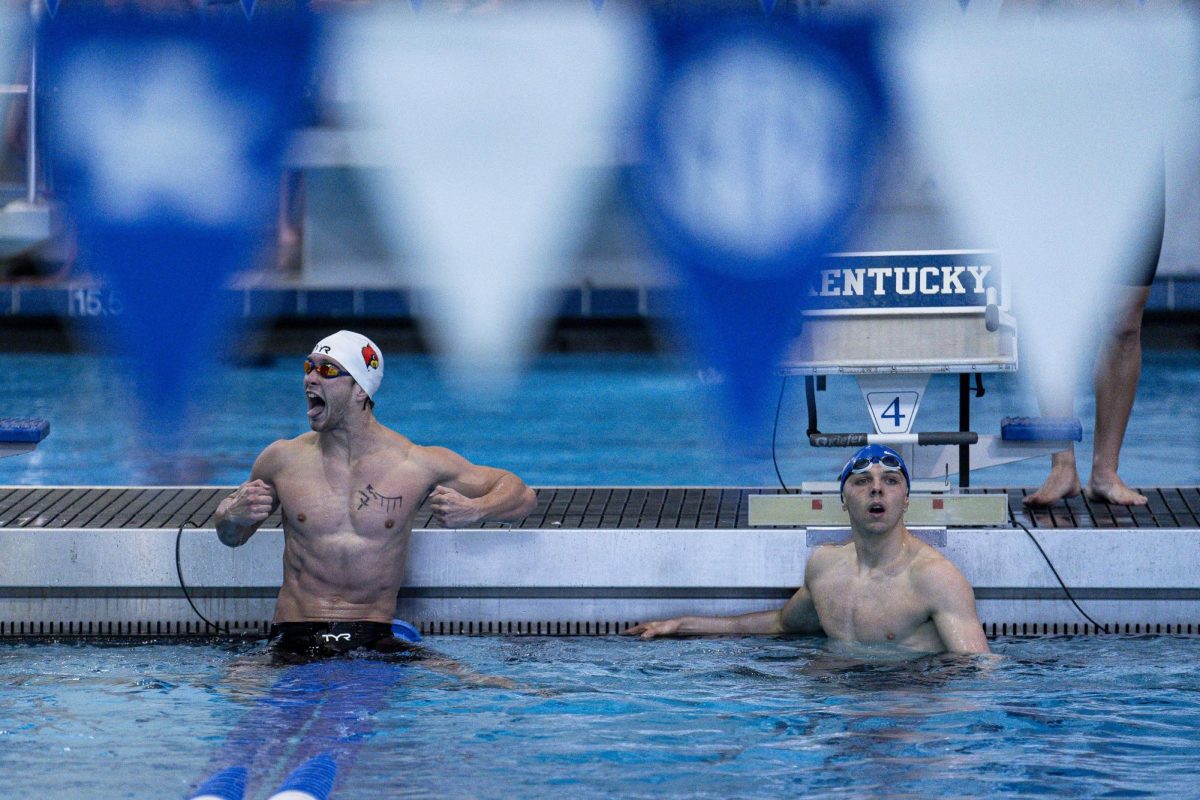

Anthony Isaacs signs to his class during a American Sign Language course in Lexington, Ky., on Monday, March 24, 2014. Photo by Eleanor Hasken

March 25, 2014

By Amelia Orwick | Managing Editor

UK instructor Anthony Isaacs’ classroom is a bit nontraditional.

Desks are arranged in a semicircle so that everyone is visible, and students are not allowed to speak.

But what is seemingly strange to most students is normal for Issacs, who was born deaf. Although some deaf people learn to speak, Isaacs never did. Instead, he became fluent in American Sign Language and certified by the American Sign Language Teachers Association.

“ASL class is full ASL immersion,” he said. As Isaacs signed, an interpretor sat behind him and spoke.

“I don’t use my voice, I have no interpreter – I’m just signing.”

When Isaacs arrived at UK in the fall of 2012, he taught two American Sign Language classes as a part time instructor.

A year and a half later, Isaacs is teaching five classes full-time, helping to implement a level-four American Sign Language class and co-advising a new club on campus.

“I didn’t grow up talking. I tried as a little boy and I wasn’t real successful,” he said. “People couldn’t understand me, I found. So I just turned off my voice and used signs.”

Isaacs was born to hearing parents. He has two sisters, one of whom is also deaf.

“When I look back to being a little kid, I felt lonely sometimes. I was kind of by myself in this big hearing world,” Isaacs said. “There weren’t too many people who could sign with me.”

But as Isaacs got older, he realized he needed to put forth more effort to be understood, he said.

Isaacs and his sister attended the Kentucky School for the Deaf in Danville, Ky., where they stayed in a dorm throughout the week.

“(KSD) will always feel like home to me, because you form very strong bonds when you’re able to communicate like that,” he said.

Upon graduation from KSD, Isaacs moved to Washington, D.C., to attend Gallaudet University, which he said is “really the only university for deaf people.”

In 2007, he received his master’s degree in deaf education from McDaniel College in Westminster, Md.

“Since 2008, I’ve been a teacher at different places, but I really love being at UK,” Isaacs said. “I feel like I’ll be here for a long time.”

This fall, UK began accepting ASL as a foreign language, and Isaacs’ inbox was flooded with emails inquiring about his courses.

Now, Isaacs teaches a variety of students at UK, some who do not wish to work with deaf people professionally. Many are communication sciences and disorders students who will go on to work in speech therapy with autistic children, for example.

Isaacs said ASL has four parameters: hand shape, movement, location and palm orientation. And many other factors play a role in signing, including facial expression, head movement and mouth movement.

“When you’re communicating with an ASL user … if you just focus on the hands, you’re going to miss a lot of the language,” Isaacs said. “It’s looking at the whole upper part of the body to get all of the meaning that’s being expressed.”

Isaacs’ quizzes are receptive, he said. Students watch him sign, and must answer his question or translate what he said in English on their papers. For final exams, students are videotaped as they translate English to ASL.

Isaacs said how quickly a student picks up on ASL is dependent on the way the student learns, how much time they spend studying and, most importantly, how much time they spend around deaf people.

To help students socialize within the deaf community and practice their ASL, the ASL Club at UK was started this fall.

Peyton Pruitt, club president, said about 20 people showed up to the first meeting, which she considered a good turnout. The next meeting will take place Tuesday.

“It’s a goal for us to teach practical stuff like introducing yourself, just so you feel more comfortable,” Pruitt said. “Obviously that can be really scary, so we want to teach students how to approach deaf people without being offensive.”

Co-adviser, Corrie Scott, said the best thing about the club is Isaacs’ involvement.

“Students enjoy it because of how they’re being asked to learn,” Scott said.

Pruitt agreed that Isaacs has been instrumental in the ASL program’s success at UK.

“Because he is deaf, he cares a lot about being respectful to deaf people, but at the same time, he’s able to have a sense of humor about things that are funny,” Pruitt said. “That balance he has being involved in the hearing community and deaf community is great.”

Isaacs said working with UK students, faculty and staff is significantly easier thanks to technology such as the iPad with its voice-recognition applications. But in instances when technology can’t help, Isaacs said scheduling an interpreter is often necessary.

“Understand that English is not my first language … ASL is my first language, so I’m more comfortable operating in that,” Isaacs said. “If I’m hurt and it’s an emergency, I’m not going to be able to think and process a bunch of English.”

Isaacs said he and some of his interpreters go out to eat together and hang out as friends.

“Sometimes, after the job is over, the interpreter will stay and we’ll talk,” Isaacs said. “I’m a big talker. I’m a chatterbox, to be honest.”

The idea of a “talkative” deaf person is surprising to many, but Isaacs said there is much that people don’t know about the deaf community.

“If you ever go to a deaf event where there’s music, just know they’re going to crank it up so loud that you can feel it,” Isaacs said. “We love feeling the beat and the rhythm.”

ASL is a beautiful language, Isaacs said, and its possibilities of expanding are endless.

“It’s very ironic, because people in public think deaf people are very quiet,” Isaacs said. “But deaf people can be louder than you think.”