He can’t sniff out bombs or drugs, but UKPD’s new dog can earn trust and respect in the community

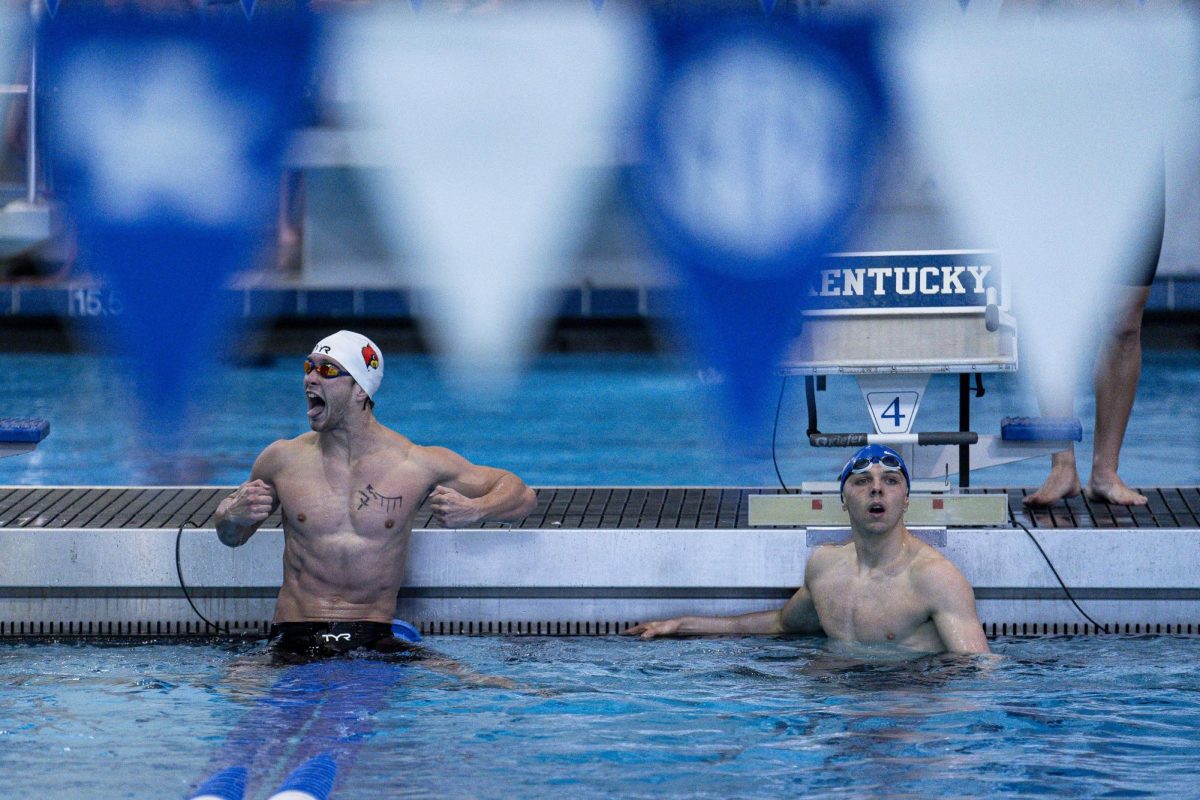

Former UKPD community affairs officer Amy Boatman tells about her 50 page master’s thesis written about the use of therapy animals in university police departments on Tuesday, January 23, 2018 in Lexington, Kentucky. Oliver was UK police department’s first therapy K-9. Photo by Arden Barnes | Staff

January 24, 2018

UK police department’s newest non-lethal weapon weighs 40 pounds and loves to chew on squeaky toys.

Oliver, handled by community affairs officer Amy Boatman, is UKPD’s new therapy K-9.

“He’s got a big stuffed hedgehog that he got a few weeks ago that he really really likes,” Boatman said.

A therapy K-9, Boatman explained, is able to do things that most officers or K-9’s can’t. Oliver, just by being a loveable dog, can step into a situation and immediately “change the environment in the room.”

“Ultimately for victims and witnesses that are having a really hard time with questioning or anything like that, he’s just a great tool,” Boatman said.

Oliver is also a great tool for breaking down the stigma that surrounds law enforcement.

“Whether they mean to be talking to the police or not, they are immediately drawn to him,” she said.

As the six-month-old poodle makes his way around campus, that much is immediately clear.

“Oh my God, a police dog,” exclaimed freshman Haniya Haque when she saw Oliver stroll into Bowman’s Den with his special UKPD vest over his curly salt and pepper fur.

After Boatman assured her that Oliver was OK to pet, Haque and her friends excitedly gave him the expected pats and belly rubs.

The puppy and his handler could hardly make it five feet without being stopped. Many students stopped their conversations and immediately fished out their phones to get Oliver on a Snapchat video. Oliver seems to love the attention.

The student population changes rapidly, Boatman said, so it can be hard to build relationships quickly.

“He’s able to break down some barriers with the community,” Boatman said. “We’re able to build some relationships we weren’t able to build before because we now have him and he changes the environment. He’s a great talking point.”

Oliver is also able to break the ice with victims or witnesses who may not be quite as open or communicative.

Boatman told the story of when she was driving to work with Oliver in the back seat. She stopped to check on a driver whose car had broken down on Alumni Drive.

“She was kind of slumped over the wheel so she looked like she was not having a good day,” Boatman said.

Boatman began to ask the driver questions about her vehicle and even tried to push the vehicle out of the road, but it was clear the driver, who was crying and not very responsive, was “having a really hard time functioning.”

“I was like, ‘I have a therapy dog in the back seat, would you like to meet him?’” Boatman said. “It totally changed her demeanor.”

Oliver calmed her down to the point where “she could function,” and Boatman could leave her with the vehicle knowing that she was safe. Boatman said this was an example of “everyday things where adding him to the situation has really made it better.”

Officers obviously witness traumatic events, and Oliver helps officers deal with those events, Boatman said.

“We respond to those scenes and we deal with that,” Boatman said. “So he not only helps with (student) stress and their issues but he also helps with the officers.”

Boatman wrote her 50-page master’s thesis on the use of therapy animals in university police departments. She contacted other law enforcement groups that use therapy dogs and conducted extensive research on the success of those animals.

Her research became a reality as Oliver joined the UKPD force, which already has three canines– two bomb-sniffing dogs and one narcotics dog.