#MeToo pioneer, victims’ advocate speaks to UK students at CSF

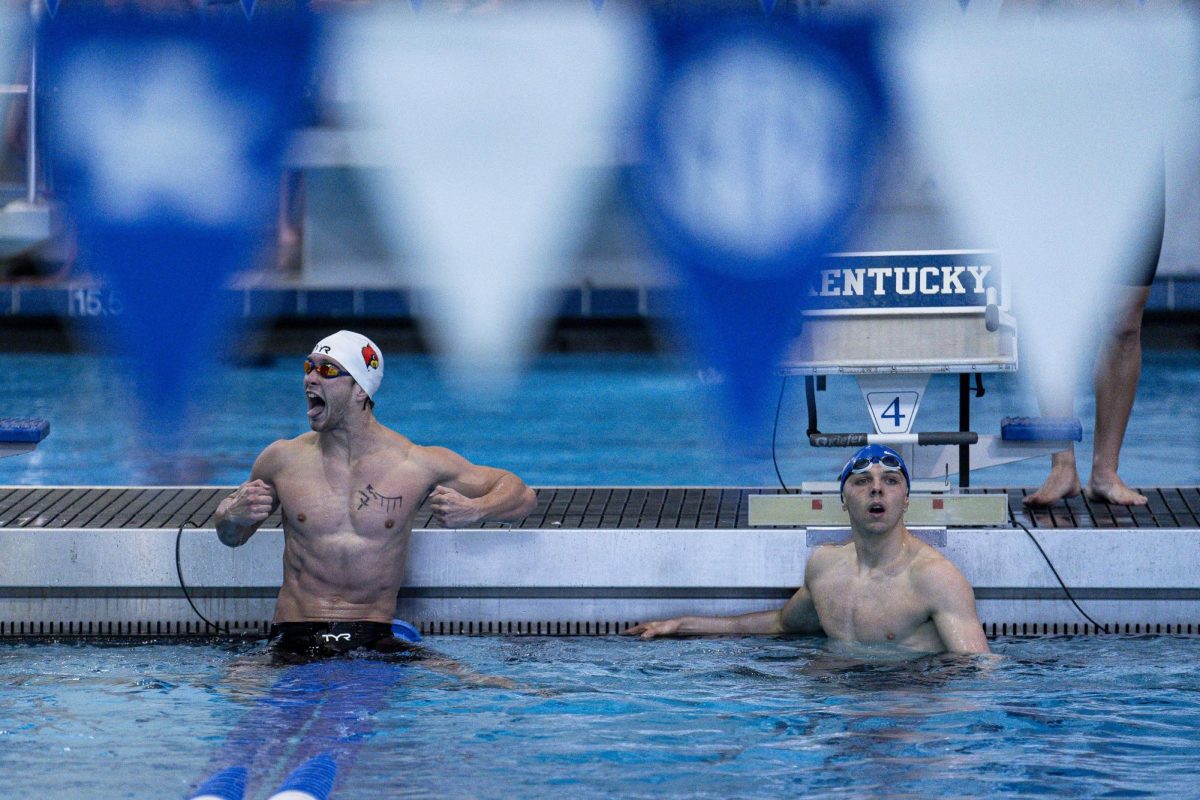

Rachel Denhollander, one of the first to report Larry Nassar and now a victim’s rights adovocate, speaks to UK students at the Christian Student Fellowship building in Lexington, Ky., on Nov. 8, 2018. Photo by Sydney Momeyer | Staff

November 9, 2018

One confession led to thousands, and a movement was started.

One of TIME Magazine’s 100 Most Influential People of 2018 came to UK this week for a Q & A, and she also happens to be known universally as the beginning of the #MeToo movement.

On Thursday night, Rachael Denhollander spoke to the Christian Student Fellowship’s weekly gathering, Synergy. CSF Pastor Brian Marshall was able to get hold of Denhollander online, where he was then directed to her team that helps her book events such as these.

“This is a conversation,” Marshall said. “Sexual assault is a conversation happening around the world. We wanted to have this important conversation here tonight, and we though there was no better person to talk about it than Rachael Denhollander.”

Marshall wanted to bring Denhollander into CSF to hopefully help those in the crowd or on campus who have had experience with sexual assault, whether directly or knowing someone who has.

“Statistics say that 25 percent or greater of people on a college campus have likely experienced some form of sexual assault,” Marshall said.

Denhollander is now a lawyer who helped bring to light a serious issue within the USA Gymnastics community. She was a former member of the USA Gymnastics team and the first woman of over 300 to come forward and state that she had been sexually assaulted by Larry Nassar, the Michigan State University and USA Gymnastics doctor.

Not only was she the first to come out against Nassar, but the confession prompted thousands of other confessions about experiences with sexual assaults from all around the nation, helping to begin the #MeToo movement.

The movement was started to express solidarity with those who have experienced sexual misconduct, and while there are different variations of it both throughout the nation and internationally, the main message is to fight against sexual assault and harassment. While many credit the movement to her, she describes her involvement in the movement as “converged.”

“The #MeToo movement was really a gift,” Denhollander said. “But it came a full year after we were already knee-deep in everything with Larry. It came a year after it was international headlines and I had already been in papers all over the world.”

Serving as their doctor, Nassar had been sexually assaulting young women for years. In 2018, he was convicted of his crimes. Denhollander came to UK to share her story and how she dealt with coming forward.

Denhollander was living in Kentucky as a stay-at-home mother when she decided to contact the Indianapolis Star to report what Nassar had done to her in hopes of shining light on the issue.

“I had actually talked to my mom a little once we kind of started figuring out what had happened and discussing and figuring out how deep Larry’s abuse was,” she said. “Mom and I had the conversation multiple times, ‘What do we do with this?’ ‘Do we go to the police?’ At that time I was about 17 when I started to understand, and I said that this can’t be done alone. I can’t do this anonymously. We are going to have to have press coverage and this is going to have to be a national story.”

The day she reported it, she had opened her email to send a grocery list to herself. Before she could do that, she noticed an article on her Facebook that caught her attention. The article read that USAG had been hiding sexual abuse cases regarding various coaches for years. The article was urging people to come forward if they had information about the subject.

“The first two thoughts in my mind were: I was right,” Denhollander said. “And it’s now. This is it. Because what I had been waiting for, for 16 years, was a sign that Larry’s ability to overcome any objections, any truth about what he was doing would crack.”

Denhollander had also been sexually abused when she was seven at her church. She went to her parents about the issue, who took action, but there were consequences to her coming forward.

“That really split the church down the middle,” she said. “The response of the rest of the church was, ‘you’ve made an accusation without proof.’ And so, by age eight I had lost my church, I had lost all of the friends I had… I was reeling from abuse that I really did not understand and hadn’t really articulated to anyone. So I knew very well what the cultural response is when you come forward.”

When other women started coming forward about Nassar’s abuse, Denhollander said she was very grateful that other women started sharing the same or similar experiences as her.

“I knew that’s what needed to happen,” Denhollander said. “I was confident there were hundreds, probably thousands, and I think there still are thousands. I think we have seen the tip of the iceberg. That’s the way abusers operate. Someone who is a serial abuser typically has hundreds of victims.”

However, since she was the first victim to come forward, she was not allowed to know the other girls’ names prior to the sentencing hearing. What she knew about them prior to that day was learned through newspapers.

“I was the oldest out of that group of survivors and I knew how hard it was going to be for those girls to testify,” Denhollander said. “I felt like I just couldn’t do anything for them. There was no support I could offer them. There was no help I could offer them. I couldn’t even know their names. So getting to meet so many of them during the sentencing hearing was very difficult but it was a real gift.”

During the event, Marshall showed a clip from the day Denhollander addressed Nassar in court during his sentencing hearing.

“When I first watched this clip, I thought, wow this woman is brilliant, brave and courageous,” Marshall said.

She also wanted to raise awareness about false reports of sexual abuse.

“You are not living in a culture where anyone can make a report and destroy someone’s life,” Denhollander said. “That’s not the reality. Statistically, out of 1,000 rapes that are committed, only 300 are reported to the police, only seven are prosecuted and only six result in jail time.”