Ironmen: UK graduate students bring state pride to world-renowned triathlons

February 19, 2009

One more stroke, one more pedal, one more step. The heat is beating down on the competitors as the hundreds of racers behind them are deafening on the burning pavement, like gazelles running for their lives.

In Kona, Hawaii, 26-year old UK graduate student Lewis Jackson has been racing for over 10 hours and is about to finish the World Championship Ironman triathlon, the pinnacle of all triathlons. He’s not going to win, but he is going to do something that the people from his “podunk town†will be proud of.

In Clearwater, Fla., Tony White is battling another racer in the Ironman World Championship 70.3 series, also called the half-Ironman. For the laid back, take-it-easy White, the day has been long.

In the end, both racers completed one of the most grueling races in the world and did so with Kentucky pride, and the people who helped them achieve this goal on their minds.

For Jackson, it started with a passion and an addiction, for White it began after a dare from friends. Along the way, it’s taken the two UK graduate students around the world and put UK, and the entire state of Kentucky, on the map.

They’re not on an athletic team at UK nor on some game show. They’re simply doing what they love and they’re doing it at an elite level. Jackson and White are ironmen.

Hometown pride

Jackson was almost 30 minutes late when he walked into the Johnson Center. He had just finished an 18-mile run and grabbed some Arby’s before an interview. It wasn’t even noon.

The simple mention of Jackson’s hometown of Eastview, Ky., brings a smile to his face. It’s a town with a post office and no real stores, and Jackson said it feels more like a “community†than anything else. About 20 minutes southwest of Elizabethtown, not many in his community dream about the type of feat Jackson is training for.

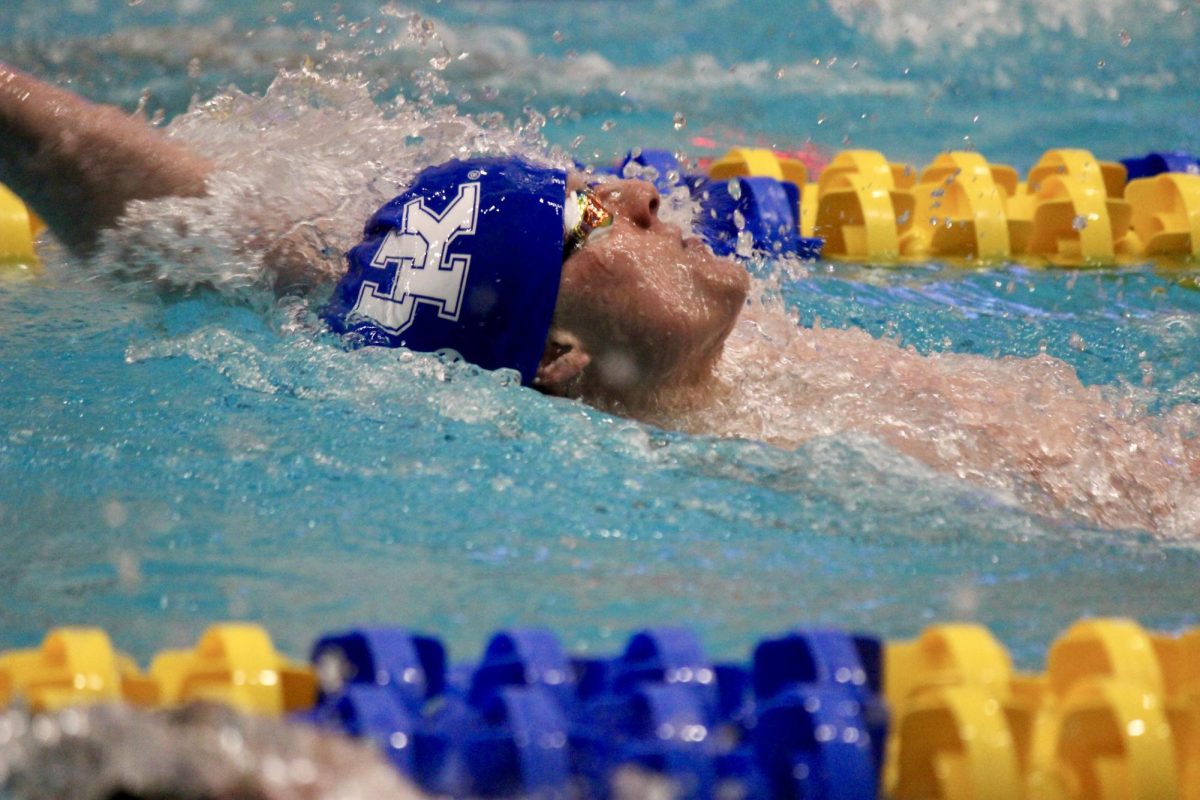

In a race where competitors swim 2.4 miles, bike 112 miles and run 26.2 miles, the ability to put mind over anything else is a necessity. For Jackson, mental focus is nothing new.

He is a graduate student working on his dissertation on early detection methods of Alzheimer’s disease. Jackson switched majors to focus on science during his junior year at the University of the Cumberlands after strong encouragement from one of his teachers.

“(That decision has) led me to be able to do research that at the end of the day will hopefully make the world a better place,†he said.

For Jackson, triathlons came about through an addicting first attempt. Being a fan of the more traditional sports such as baseball and football as a kid, Jackson wasn’t born to race in triathlons. But in the summer of 2001, he needed an alternative to swimming. After one triathlon, nothing else in the world mattered, he said.

“(We thought) that he had no idea what he was doing,†Jackson’s mother, Judy Smith, said. “He didn’t know anybody who was doing them or grow up around anything like that. We thought it was crazy.â€

Jackson thinks differently than many athletes. For him, it isn’t the end product that gets his adrenaline pumping; it’s the training that goes on for ten months of the year. He trains in cycles, gradually picking up workouts and paces before tapering back down as the triathlon approaches.

“You have to be more addicted to the adrenaline you get from training than racing,†Jackson said. “Racing is such a small part of triathlons. If you’re spending 15 to 20 hours a week training, and you’re only going to race two to three hours every month, you have to be in love with the training or it’s not going to be any fun for you.â€

That mindset helped Jackson gain a spot in the Ironman World Championship in Kona, Hawaii, in his second attempt at qualification. In that first trip to the World Championship on Oct. 11, 2008 — in nearly 40 mile per hour winds and heat topping 100 degrees — Jackson finished the race in 10 hours, 37 minutes and 32 seconds.

And while many competitors were crossing the finish line carrying flags of their countries, Jackson carried the Kentucky state flag.

“I want to be the inspiration for that kid in that small Kentucky town,†Jackson said. “I always had a lot of support from my parents. I feel like Kentucky is ranked near the bottom of every level, in education, in health, in poverty … I feel like the kids think they have to stay in that position. I carried that flag across to show every kid that the only limits in this world are the ones that you put in your mind.â€

Crossing the finish line

Tony White, a health promotion graduate student, is a movie junkie and loves food — devouring just about anything in front of him.

“He walks into our house and goes straight to the kitchen and the cabinet,†White’s triathlon coach, Beth Atnip, said. “I don’t think he even says ‘hi’ sometimes.â€

But there’s more to White than just being a normal UK student. For him, a competitive nature was something he was born with. Whether it’s pingpong, swimming or basketball, a winner is always crowned for the White family. That competitive drive led the 24-year-old from Corbin, Ky., to start running after his friends dared him to try out for his high school cross country team.

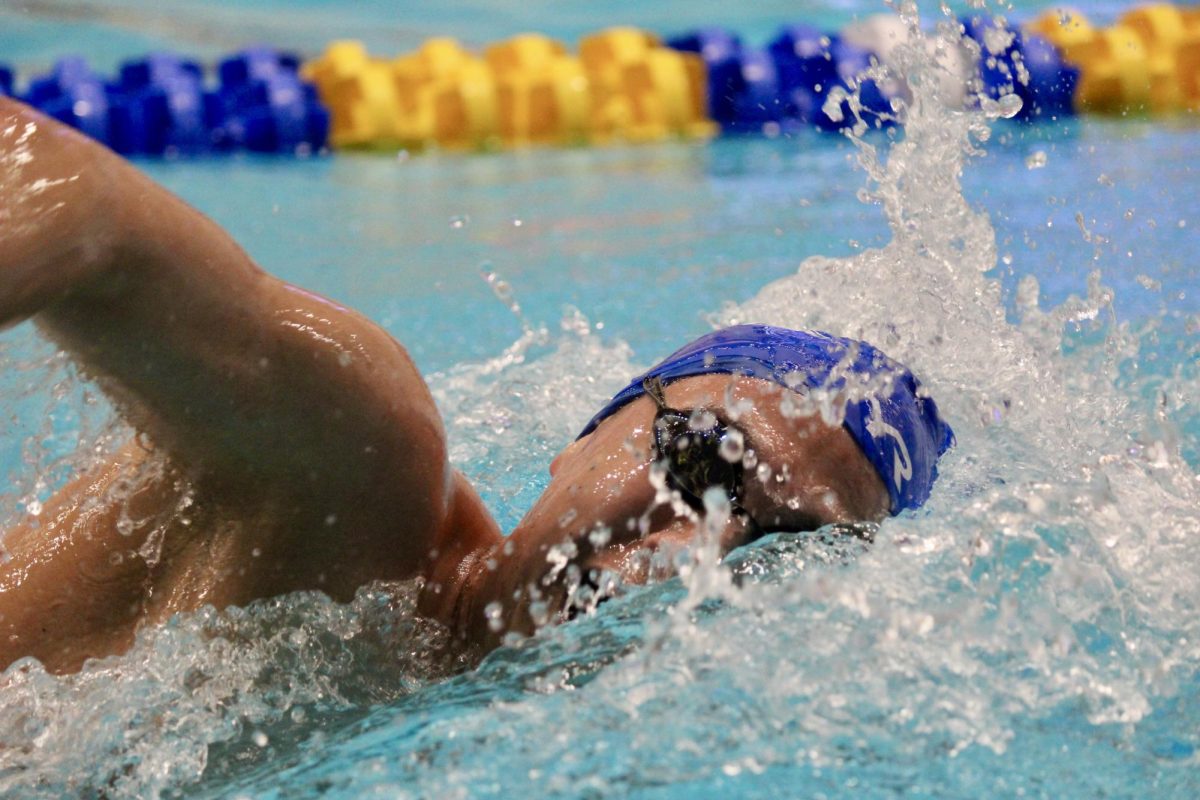

After that dare turned into a love, White got into triathlons by way of staying in shape during an injury, swimming as often as possible.

In his first 5K, he walked the second mile. He struggled to complete the long-distance runs with the team without walking. But by the end of the year, his drive and motivation had him just five seconds behind the fastest person on the team.

“The advancements he’s made in the last few years are more than what some people could do in a lifetime,†Atnip said. “It makes you think the future is great for him.â€

After some decent results in the first few triathlons, he felt triathlons were something he could continue to pursue. At first he stuck to the Olympic distance races, which span .93 miles swimming, 24.8 miles biking and 6.2 miles running. But his own competitiveness and encouragement from his coach led him to train for the half-Ironman, or Ironman 70.3 series. He was preparing for a 1.2-mile swim, 56-mile bike ride and 13.1-mile run.

“He doesn’t like to settle for second best,†White’s mother, Joy, said. “The hardest person on Tony is himself. He doesn’t do it for recognition or anything else, he does it for the love of it.â€

White began to clock in better times and his confidence began to soar, something he believes may be even a bigger aspect of the races than the physical.

“I pictured myself crossing that finish line in first the whole time,†White said. “It sounds kind of cliché but when you picture yourself doing well, you will do well. If you don’t see that, you won’t.â€

White finished with a time of 3 hours, 54 minutes and 24 seconds at the World Championships in Clearwater, Fla. — his first complete Ironman 70.3 series. It was the second fastest time in the world among amateurs and fastest among amateurs in the U.S.

“I did the race in my UK triathlon suit,†White said. “I had Kentucky written across my chest.â€

‘Just go out and try it’

While they share an interest to make it to a higher level of competition, both men feel accomplishment in what they are doing now.

“Triathlons will always be a part of my life at the amateur level,†Jackson said. “I know that my talent is very limited. I would rather just be a really good amateur all my life. I know I don’t have the talent to go to the next level, but I’m fine with that.â€

The full Ironman is a goal for White, but he’s saving that for down the road. For now, White plans on continuing to do half-Ironman competitions for a year or two professionally and seeing where it takes him.

Whether it’s state pride, a passion that won’t let up, a desire to never be second or an itch that can’t be scratched, Jackson and White have a ticking time bomb of self-motivation with a seemingly endless fuse.

“Life is so short, don’t just look at what somebody else is doing and be like, ‘man I wish I could do that,’†Jackson said. “Just go out and try it.â€