Fighting to recognize UK’s first black employee

February 7, 2016

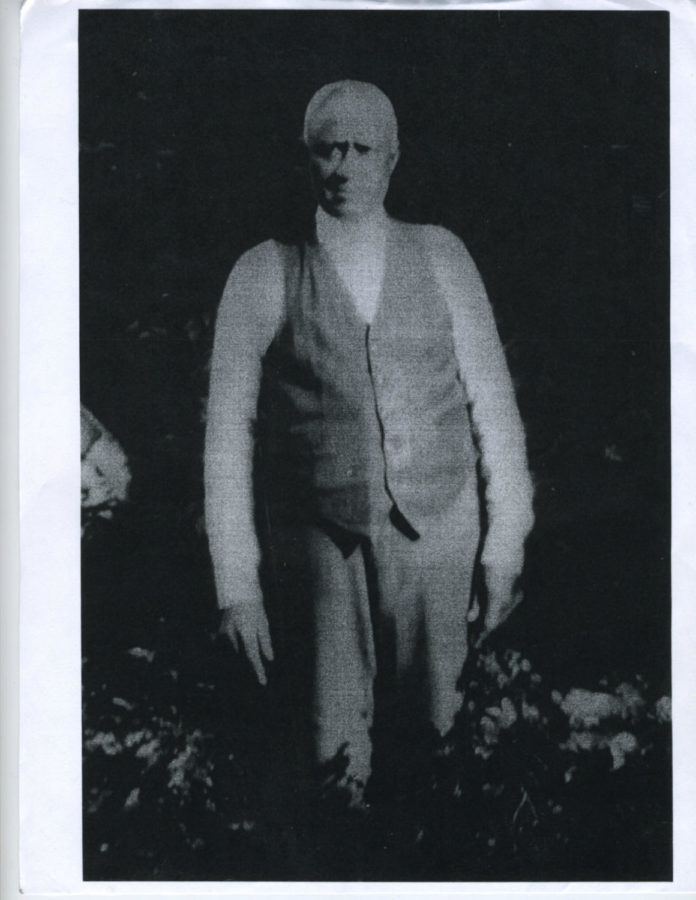

Pierre Whiting began his career at UK as a barefooted child, carrying water to construction workers who were making bricks for the Main Building. He went on to become an institution, part of the fabric of race relations on a campus that would not accept black students for another 70 years.

Whiting, or “Dean Whiting,” as students called him, was a storyteller, a role model and, most importantly, a symbol of equality and mutual respect between whites and blacks.

UK grad Kalvin Graves has researched Whiting, born in 1861, for about two years, pouring through old newspaper records and minutes from board meetings, putting together the puzzle pieces of a life largely forgotten by the campus he loved.

UK’s first black employee died in 1949, the same year the first black student, Lyman T. Johnson, won his right to attend UK after a legal battle in federal district court.

Now, with race relations making headlines on campus and throughout the country, Graves feels it is time to hang a portrait of Whiting in the Main Building.

“His spirit is still in that building,” Graves said. “I know it is because he helped build that building as a little boy.”

It took 2 million bricks to build the building, bricks that were formed by the hands of mostly black workers. But Whiting’s hands did more than help create the infrastructure of campus. As a janitor, Whiting became a pseudo-celebrity among students in White Hall — originally a dorm where Whiting worked.

Newspaper clippings speak of Whiting as a role model for students despite the obvious racial divides in Lexington at the time.

“Students loved him,” Graves said. “I think he did lay the groundwork for what the expectations were for African-Americans … on campus.”

Whiting lived in Adamstown, a black neighborhood that stretched from the current location of Memorial Coliseum almost all the way to Broadway. Many residents worked at UK, but also throughout Lexington, laying bricks and building homes — many of which still stand.

The community built a relationship with the university based on both employment and proximity. Residents stood on their roofs to watch some of UK’s first football games – games they were not allowed to attend.

This is Graves’ second mission: get the university to recognize Adamstown with a historical marker near Memorial Coliseum. Graves will, within the next few weeks, take a proposal and historical information to Frankfort and apply for a historical marker. He will then contact UK to see if the university will allow the marker to go in front of Memorial Coliseum.

Graves said to not honor Whiting — a man who dedicated his life to building the university both structurally and socially — would be a tragedy.

“With the climate that is going on at UK … he brought people together,” Graves said. “I think it is a shame that we do not have something to honor him.”