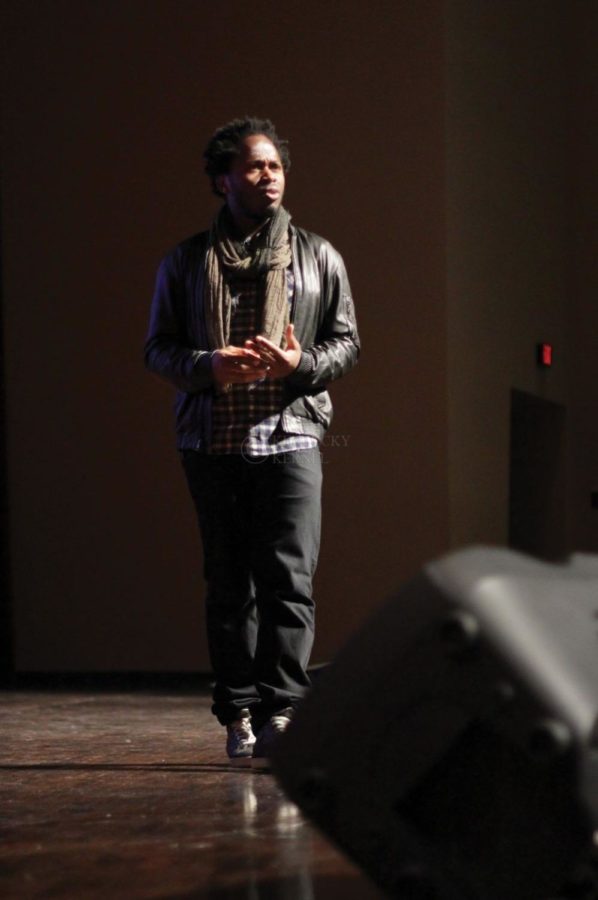

Author speaks about time as boy soldier: Common reading writer tells students about his book and experiences

October 29, 2014

By Nick Gray

When his family was killed by militants in Sierra Leone during a civil war in 1993, Ishmael Beah, then a 12-year-old, said his ability to trust turned into a fear to do so.

Beah, now 33, wrote about his childhood as a boy solider in Sierra Leone and going through rehabilitation and life as a foster child adapting to the New York City lifestyle in his memoir, A Long Way Gone.

The memoir was the Common Reading Experience for this year’s freshman class and culminated in Beah’s speech Tuesday at the Singletary Center.

The book detailed Beah’s emotionally challenging and harsh childhood, beginning with the murders of his immediate family.

“That was the moment that changed my life,” Beah said. “That changed my relationship with life and the world that I lived in. So for the rest of my childhood and life, I fought that.”

Beah was a child soldier for the Republic of Sierra Leone Armed Forces, the side opposite the militants who killed his family. After he was taken away and rehabilitated from a military life of violence and drugs, his ability to relate to people and trust them was at his lowest when he met his foster mother, Laura Simms, he said.

“As a young adult, I could see that I could not go on through life with the possibility of not trusting,” Beah said. “I had to learn how to be a son to her, and she had to learn how to be a mother to me, especially since I was her only child.”

But Simms’ persistence and the normalcy of being a child to a mother finally wore the resistance down.

“There was never a set moment,” Beah said. “It was a lot of regular memories that were collected together and helped everything become better. All those memories helped make a whole relationship between us.”

Beah said he wrote and published his memoir at age 26 to describe what violence at such a young age can do to an individual, as well as how difficult the journey back to the normalcy he reached can be.

“The idea behind it is that I wanted to put a human face to the issue (of violence and children in war),” Beah said. “Now you think about the issue in conflict, you can think that if this was my brother, my sister, my child, that I would not accept it.”

Beah said he resented the picture the media painted of the Sierra Leone civil war as an extremist movement that implied that something was fundamentally wrong with his home country.

“This is a place where people did not just wake up and decided to have a civil war,” he said. “There are things that led to this. The media presented it as a sensationalist mode and a fear-mongering methodology, and I wanted to change all this to give human context to what it means to live in war and for a child to live in war.”

As he prepared to speak to the Singletary Center crowd, Beah said he believes he has succeeded in at least creating talking points for those looking for change.

”There are some parts in the book where I say, ‘We are a long way gone (from) where we have been,’” Beah said. “It didn’t say we are gone forever. It leaves the possibility of coming all the way back.”