Look beyond the mug: Coffee hurts environment, laborers

October 16, 2009

Column by Cassidy Herrington

When the crisp chill of fall embraces the air, people flock to coffee shops, as if from animal instinct, roused by what I call “coffee- drinking weather.â€

The metallic urns spill warm, bold roasts into paper cups, and espresso machines delicately drip pungent espresso into porcelain demitasses. In a choreographed dance, baristas hourly grind pounds of coffee beans and steam gallons of milk for each foamy latte or cappuccino.

And you, my dear coffee shop frequenter, smugly wipe the foam off your lip and pretentiously turn the next page of your book, perhaps without even considering what it really takes to create the seemingly simple concoction in your grasp.

And who am I to say anything? To start, for three incredible, thankless and exhilarating years, I worked in a fair trade coffee shop. I woke up at 4:30 every morning to a queue of decaffeinated businessmen and women, blue-collar workers, soccer moms, “beardos†and philanthropic activists.

Every day was a lesson about paradoxes. For example, people who dump sweeteners into their coffee may not be very sugary themselves, or customers who want their drink “nonfat†may still ask for eight pumps of syrup and a squirt of whipped cream.

Working in a near opposite microcosm, I went to Guatemala for a month and witnessed the unseen struggles of coffee farmers and laborers. I spoke with locals who worked tedious, manual labor for a full week to make what most baristas in the U.S. make in a single shift on minimum wage.

But the point is, there is so much more to the toasty beverage steaming in your plastic “eco-friendly†thermos. In fact, there is another world. It involves corruption, poverty, a genuine environmental conflict and our responsibility as global citizens.

Just continue reading and enjoy your coffee.

The interior of a coffee shop emits a cozy, sophisticated feel, and for business, this is a profitable scheme.

However, the sophistication leaves the truth out of sight, out of mind. The sleek designs and elegant furnishings further dissociate the coffee drinker from the source.

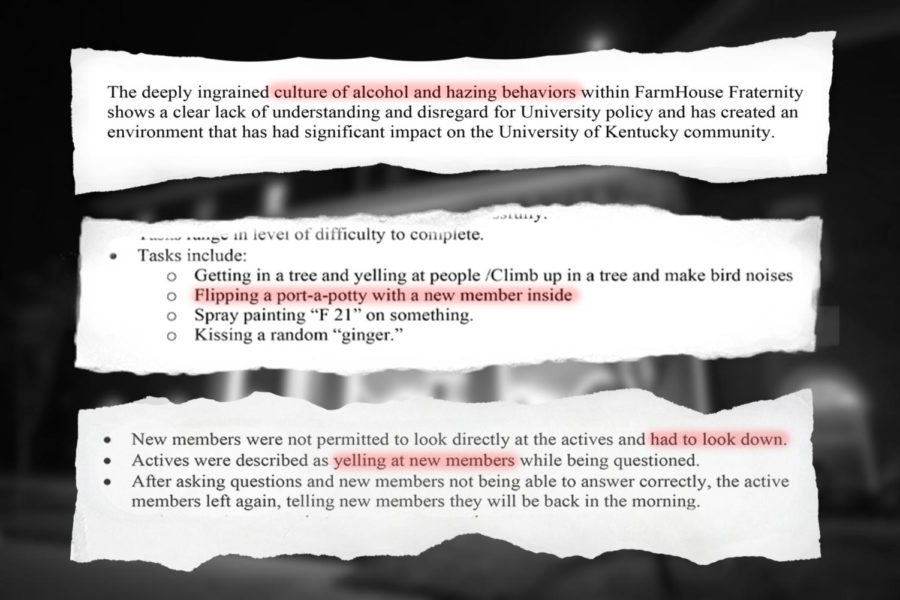

When coffee harvesting begins in September, the farms in Guatemala, Rwanda, Indonesia, Ethiopia, Peru, Colombia and many “third world†countries call upon its workers to harvest millions of small coffee cherries for coffee production. Some 20 million people near the equator rely on coffee for their livelihood.

The labor is intensive, for coffee farms are under the authority of nature, rather than human hand. (Good) coffee grows in high altitude and under shaded plants, so extracting the product involves strength and vigor. These laborers have plenty, for they are starving and have mouths to feed.

With a sack slung over her shoulder and child in tow, a mother harvests the red coffee cherries in the thin mountain air. She climbs higher, and the weight of her sack grows heavy on her small frame. Her pay is not hourly, but rather, by the weight of the produce in her bag.

According to the U.S. Labor Education in the Americas Project, in Guatemala, a temporary seasonal coffee laborer earns $2.50 for harvesting 100 pounds of coffee cherries. Depending on the season and number of family members working (children included), a family can pick between 50 and 300 pounds per day.

Where does the profit go? Speculators, big roasters and middlemen get most of the profits. Not the farmers, nor the laborers.

This is where fair trade comes in. The Fair Trade Labeling Organization International identifies, registers and certifies companies who guarantee a premium (above market rate) price and humane working condition for laborers. Fair trade insists on human rights and opposes child and slave labor.

Back to our “first world,†coffee is the second most heavily traded legal commodity in the world, after oil. Starbucks is no more sophisticated or unique than a McDonald’s, they have over 16,000 franchises worldwide.

The enormity and widespread popularity of the beverage brings another concern: the damage these establishments inflict on the environment.

Senior Vice President for Market Transformation at the World Wildlife Fund, Jason Clay, speaks to corporations big and small about sustainability and reducing environmental impact while maintaining productivity. After extensive research, Clay found that a single latte requires an estimated 200 liters of water to make. The water required goes into the packaging, cultivation of coffee, nourishment of the cows and the sugar that creeps into many coffee beverages.

And his study only concerns the water. His study does not even begin to address the amount of paper wasted and the mountain of plastic that fails to meet the recycling bin.

I do not mean to sour the luxurious coffee taste in your mouth, but maybe it’s time we reevaluate our posh, overlooked commodity.

Be wary of how great your “coffee trail†is by eliminating the use of packaging. Make this fall the time to become mindful of the “invisibles.â€

Search out organizations that are committed to workers’ rights. Although the people involved in coffee harvesting are thousands of miles away, we share a global community.

Given that you have absorbed the caffeine and seen the complexities swirling in your mocha, take satisfaction in the moment you took to see the world at large and act upon the awareness, one mug at a time.