Calling the shots: Officials work long hours for love of game

September 11, 2009

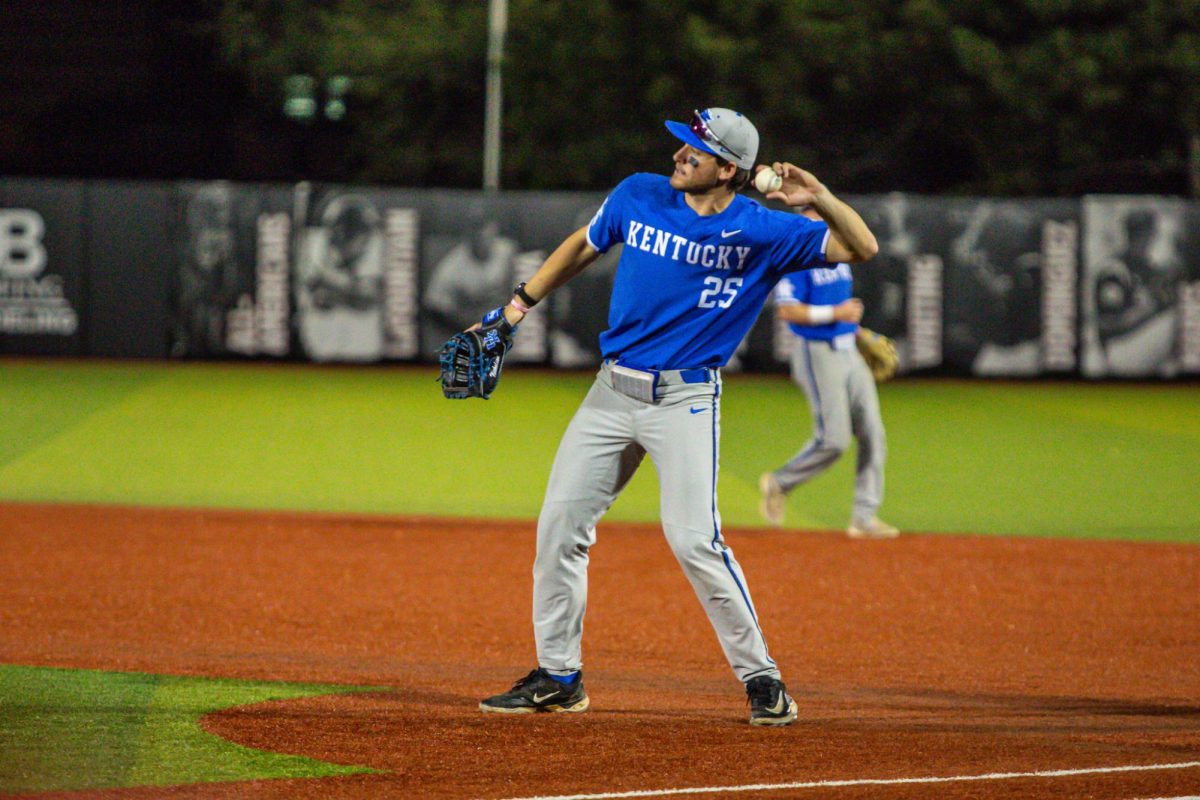

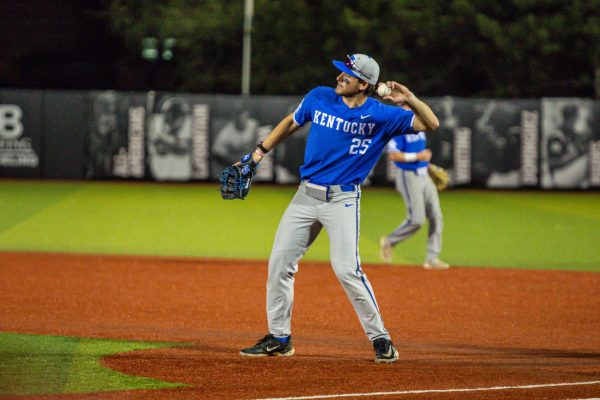

They make an unpopular call and they are criticized. They miss a call and they are vilified. This is just part of the job for any official in any sport.

Despite the chorus of jeers and heckles that is the accompanying soundtrack of many officials’ jobs, the official plays an integral role in overseeing the fair competition of a sporting event, from the professional sports leagues to the youth leagues and even in intramural leagues

Every year, the UK Intramural Office employs a wide range of students, graduate and undergraduate, Greek and non-Greek, experienced and inexperienced, with varying majors and backgrounds, as officials, said Charlie Burk, UK’s intramural director.

Burk, who officiates high school sports as a side job, said this “melting pot†of students is trained to deal with the life as an official, which includes the rules of the sports, how to enforce these rules and to be ready to deal with the occasional “nuttiness.â€

“I’ve never been thanked by a team for winning them a game,†Burk said. “I have been blamed for losing.â€

The passion many competitors, who often resort to intramurals as their only outlet for sports, bring to the playing field challenges the officials to stay composed and remain confident of their calls at all times.

Landscape architecture senior and intramural official Simone Heath recalls making a controversial call in a fraternity flag-football game that lead to the entire losing team yelling at her. On the last play of the game, near the back goal line of the endzone, the offensive and defensive player caught the ball simultaneously. Heath ruled the catch a touchdown because, according to rules, the advantage goes to the offensive player in such a situation, she said.

Two years ago, official Danny Amon experienced a situation almost identical to Heath’s. Amon also ruled in favor of the offensive player.

“The team blamed me for an entire season,†Amon said. “They are looking at your stripes, not who you are as a person.â€

Exercise science junior Tyler Long has a method for coping with the tough calls he has to make.

“I really don’t care what people think,†Long said. “Half the people on the field will not like the call you make.â€

Teams are allowed to dispute calls, but the official’s call is rarely overturned since the use of instant replay is not available at the intramural level.

Heath, Amon and Long are trained to officiate all of the intramural games, a list that includes soccer, basketball, softball, flag football, dodgeball and ultimate frisbee.

An average work shift lasts from 4:30 p.m., to about midnight on hourly minimum wage pay. During a shift, officials usually call three to four games. Most nights there are 24 to 28 officials working, along with supervisors. In total, 50 to 55 officials are employed, the “ideal†number, Burk said.

Neither Heath nor Long expected much to come of their job. Both applied for the position because of the convenience of working on campus, and the friendly vibe they received from the intramural office.

“At first I just wanted some money,†Heath said. “But I really like officiating. It helps your decision making and keeps you thinking on your feet.â€

Long views his job as more of a temporary career.

“I like it because it’s a job around sports,†Long said. “I’ve made friends and have a good time doing it.â€

Amon, who graduated in 2008 with a degree in psychology, gained his certification to officiate high school sports in Kentucky. He will start out calling junior varsity and middle school games.

“There’s no better feeling than knowing you called the best game you could,†Amon said.